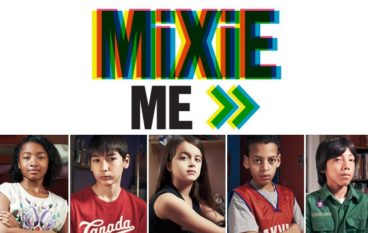

A new mixed-raced generation is transforming the city: Will Toronto be the world’s first post-racial metropolis?

I used to be the only biracial kid in the room. Now, my exponentially expanding cohort promises a future where everyone is mixed.

Last fall, I was in Amsterdam with my parents and sister on a family trip, our first in more than a decade. Because travelling with your family as an adult can be taxing on everyone involved, we had agreed we would split up in galleries, culturally enrich ourselves independently, and then reconvene later to resume fighting about how to read the map. I was in a dimly lit hall looking at a painting of yet another apple-cheeked peasant when my younger sister, Julia, tugged at my sleeve. “Mixie,” she whispered, gesturing down the hall.

“Mixie” is a sibling word, a term my sister and I adopted to describe people like ourselves—those indeterminately ethnic people whom, if you have an expert eye and a particular interest in these things, you can spot from across a crowded room. We used the word because as kids we didn’t know another one. By high school, it was a badge of honour, a term we would insist on when asked the unavoidable “Where are you from?” question that every mixed-race person is subjected to the moment a conversation with a new acquaintance reaches the very minimum level of familiarity. For the record, my current answer, at 30 years old, is: “My mom’s Chinese, but born in Canada, and my dad’s a white guy from England.” If I’m peeved for some reason—if the question comes too early or with too much “I have to ask” eagerness—the answer is “Toronto” followed by a dull stare.

At some point, spotting mixies became a kind of sport for us. “Mixie baby,” Julia would hiss, chin-nodding toward some racially ambiguous kid in a stroller at Christie Pits Park. “Mixie,” I’d say, the moment Kristin Kreuk—the super-attractive but heartbreakingly boring Canadian star of Smallville—appeared on the television.

We pointed out others because…well, it’s hard to say why, exactly. Because we secretly longed to make a silent connection with people with vaguely comparable racial experiences? Because of some ingrained tribalism that made us seek out the genetically similar? Or maybe because, back in early-1990s Toronto, mixed-race people were rare enough that they were worth pointing out, the same way you might point out a cardinal flickering through the trees or an original Volkswagen Beetle.

My sister and I have mostly stopped whispering “mixie” at one another in crowded areas. It’s dawned on us that pointing out the race of passersby might be offensive. And in 2013, mixed-race Torontonians have become almost commonplace. At Lord Lansdowne, my elementary school at College and Spadina, I was the only mixed-race kid in my grade. Today, the school is thick with mixies bearing features from all over the map.

According to the 2006 census, 7.1 per cent of GTA marriages were interracial. In a city of immigrants, that number will rise exponentially over the coming years. In less than two decades, Statistics Canada predicts that 63 per cent of Torontonians will belong to racialized minorities, the current term for those of us who are a shade other than white. More than half of second-generation visible minority immigrants who are married have partners outside their race; by the third generation, it’s 69 per cent. Those couples are having kids and those kids will one day have kids of their own, marrying across racial lines and producing a myriad of mixie babies.

In the gallery in Amsterdam, I followed my sister across the room to a painting of some 17th-century merchant and his family. I looked closely at the wife. Dark hair, pursed lips, and something unmistakable around the eyes. The plaque explained it: Pieter Cnoll with his Eurasian wife, Cornelia van Nieuwenrode, the daughter of a Dutch merchant and his Japanese concubine. A mixie. Perhaps the earliest one I’d ever seen.

If you’re a certain type of mixed-race person, you don’t look for your tribe in the faces of people over a certain age—after all, how much mixing really went on in Toronto bedrooms in the 1940s? I’d never spotted my arrangement of features in a senior citizen on the streets of Toronto, let alone in an oil painting in a national museum. For a moment, though, I took a little pleasure in imagining a future in which art galleries and magazines and television shows were filled with mixies. It’s a future that, if it happens anywhere, will start in Toronto.

Historically, mixing the races was a sin and then a crime and then, after years of slow progress, merely a terrible thing to do to an innocent child who would be forever torn between two worlds.

This last period was surprisingly long-lived. In the 1860s, a French anthropologist argued that mixed-race people, like mules, would forever be sterile and miserable. Theories by people such as Charles Davenport, a leading, early-20th-century advocate of eugenics in America, posited that multiracials suffered from emotional and mental problems. There were studies by sociologists and psychologists well into the 1980s claiming that biracial individuals were inevitably confused, anxious and poorly adjusted. Multiracialism was seen as a pathology.

Crossing racial boundaries could result in awful consequences, in Canada as much as other places. In 1930, 75 hooded members of the Klu Klux Klan caravanned from Hamilton to Oakville to prevent a young white woman from marrying her black fiancé, burning crosses with the indulgence of local law enforcement. In 1939, 18-year-old Velma Demerson was deemed “incorrigible” and jailed after taking a Chinese lover.

The first big Canadian examination of what it meant to be mixed was the book Black Berry, Sweet Juice by Lawrence Hill, the journalist and novelist best known for The Book of Negroes. Published in 2001, Black Berry, Sweet Juice is part memoir about growing up the son of a black father and a white mother in Don Mills in the 1960s, and part survey of other biracial Canadians.

For Hill, growing up black and white was a puzzling and painful process, trying to sort out an identity at a time when the options available to a brown-skinned man in lily-white Don Mills were limited. Hill says he’s always thought of himself as black, though he’s not sure he had much choice. “When I was a boy, I suppose I could have walked around telling people, ‘I’m not black. I’ve got one black parent and one white parent, and I consider myself biracial,’ ” he writes, “although any person who felt negatively disposed toward black people would hardly have been kinder to me as a result of this self-definition.”

Well into the 1980s, psychologists claimed that biracial individuals were inevitably confused, anxious and poorly adjusted. Multiracialism was seen as a pathology

Little more than a decade later, Black Berry, Sweet Juice feels like a relic of another time. This isn’t to say that the difficulties and anxiety Lawrence Hill wrote about have disappeared, particularly if you’re part black, which remains fraught with a specific set of complications. But many things have changed, and drastically. The Toronto that Hill and his generation grew up in was overwhelmingly white. The Hills were the only black family in their suburban neighbourhood, just a bus ride away from my mother and the rest of the Hunes, as far as they knew the only Chinese family in theirs. My mother casually says things that sound like hyperbole but are literal truth, like: “I was the only Chinese hippie and your aunt was the only Chinese divorcee.” For a mixed-race person in 1960s Toronto, there was little chance of blending into the background.

For today’s mixies, growing up multiracial has meant inner debates about which parent to identify with, how to explain one’s background, and coping with the urge to blend in. Rema Tavares, a half-Jamaican 30-year-old with curly hair and light brown skin, says her looks have provoked strange responses in people. “I’ve had someone say to me, ‘Don’t say you’re black because you don’t have to be. You can get away with it!’ ” She was raised in a small town outside Ottawa and gradually moved to bigger and bigger cities. “I hated being the only person of colour on the bus in my hometown,” she told me. Another mixed-race woman, Alia Ziesman, grew up in Oakville and was so ashamed of her mother, an ethnically Indian woman from Trinidad, that she refused to walk on the same side of the street as her. Ziesman and Tavares and everyone else I spoke to agree that it is a pleasure to be in a city like Toronto today—a place where you’re guaranteed not to be the only coloured face on a city bus.

I feel my mixie-ness most acutely when I leave the city. When travelling through Latin America, I am constantly referred to as Jackie Chan, who is apparently the world’s most famous Asian. For a few years, I played in an indie rock band that toured across the country. A rock show anywhere is a conspicuously white event, but a rock show in Lethbridge or Fredericton is perhaps the purest white experience you can have without joining some CSIS-monitored fringe group. In these places, it feels like there’s little opportunity for you to explain the subtle intricacies of your background. Against such a white backdrop, I am pretty obviously Chinese, but when my sister travelled in China she was branded a gweilo westerner.

Returning to Toronto always comes with a palpable sense of relief. There are relatively few places in the world where a mixed-race person can walk around and be treated with such welcome indifference.

In recent years, mixed-race people have gone from a minor curiosity to the subject of a humming academic discipline. Ethnic studies departments have opened for the first time, driven in part by the ever-increasing number of mixed-race students on campus.

Minelle Mahtani, a U of T associate professor, is one of the pre-eminent Canadian authorities in the field, and has just written a book on multiraciality in Canada. Mahtani has long, dark hair, a toothy smile and a collection of features that are impossible to place on a map. When she was growing up in Thornhill, people would guess at her background without ever hitting on the actual mix, Iranian and Indian. “As a kid, I was one of the few minorities in my neighbourhood, and there was pressure to acclimatize to whiteness” she says. When I met her in a café near U of T in December, she had recently come back from the second Critical Mixed Race Studies Conference at DePaul University in Chicago, a four-day exploration of race and racial boundaries that also acts as a place for mixed-race academics from across North America to hang out and share nerdy in-jokes about the successful 1967 challenge to Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws.

The Chicago conference included panels on mixed-race children’s literature and multiracial representation in museums. Academics with geographically specific interests could learn about the historical mixed-race populations of the Carolinas, Virginia and Appalachia, or sit in on a panel called “Historical and Media Representations of Mixed Race in Japan.”

Mahtani led a round-table discussion about the future of mixed-race theory in Canada, which addressed such subjects as mixed characters in African-Canadian literature and the continuing impact of Canada’s history of colonization.

Instead of being seen as tragic individuals, the mixies of today are being talked about in a far more romantic light. Mixed-race people are portrayed as the harbingers of a utopian future in which “race,” that petty construct, ceases to exist and we all live in harmony—beautiful and content in our exotic, beige-ish glory. Some studies have made the dubious claim that mixed-race people are biologically more attractive, turning those old eugenics-based theories on their head: the same “hybrid vigour” that creates a good sorghum crop apparently also produces healthy, symmetrical beauties like Halle Berry and Keanu Reeves.

There’s a basis for some of this optimism: the 2006 Canadian census showed that interracial pairings are on their way up, growing at a much faster rate than same-race marriages. As a group, mixed-race couples were young and urban and tended to be more highly educated: one in three people in mixed-race relationships had a university degree, versus just one in five people in non-mixed unions.

In the U.S., the Pew Research Center published a study on intermarriage based on the 2010 census that showed similar trends. Marriage across racial lines had doubled in 30 years, and the numbers around “acceptance” were striking. In 1986, only a third of Americans thought intermarriage was acceptable for everyone. Today, 63 per cent of Americans say it “would be fine” with them if a member of their family married someone outside their race. The study also showed that Asian-white newlywed couples tended to have higher earnings than any other pairing, including white-white or Asian-Asian pairs.

Both studies—along with the election of U.S. president Barack Obama, the world’s most famous mixie—prompted a flurry of media reports and articles hypothesizing that the increase in mixed-race couplings would usher in a new era of equality. The fact that Asian-white pairings were so successful was touted as the beginning of a “post-racial elite.”

The increase in mixed marriages, the Globe and Mail hypothesized, was evidence that “multiculturalism is working in Canada because mixed unions—and biracial children—break down barriers on perhaps the most personal of levels.” It’s tempting to dub the many new mixies, say, the Drake Generation—an idealized cohort of Torontonians who move fluidly through different identities and cultures. If you believe the hype, mixies promise a utopian post-racial future—the city’s motto, “Diversity Our Strength,” in human form.

The reality of being mixed is far more complicated. The Pew study didn’t reveal a world where skin colour is irrelevant: a newlywed Hispanic-white couple will earn more than the average Hispanic couple, yes, but less than the average white couple. The same is true of black-white pairings. What’s also clear is that mixing doesn’t happen evenly. The success of Asian-white couples like my parents can be attributed to a number of things, but the fact that immigration laws often hand-pick the wealthiest, most educated, most outward-looking Asians is surely part of it. It’s easy to imagine a future in which upwardly mobile Asians and whites mix more frequently, while other minorities are left out of a trendy mixed-race future. Marriage across racial lines is increasingly possible, but mixing across class has always been tricky. And class, it goes without saying, remains stubbornly tied to skin colour.

In 2000, Americans were allowed for the first time to mark themselves as more than one race on the official census. The new option came after years of lobbying by organizations such as Project RACE (Reclassify All Children Equally), a group led by the white mother of a mixed-race child. It was a victory of sorts, the kind of change that at last allows a young multiracial person to recognize all sides of his or her identity without being forced to choose camps. Some critics, however, saw it as an effort by white mothers to avoid having their child identified as “black” on the census. The celebration of a fashionable new mixed-race generation can threaten to leave other people behind. Proclaiming your “mixed-race” identity can be a way to opt out of being black or First Nations or Chinese and lay claim to a slightly higher status—“mixed race,” an exotic, desirable new identity unencumbered by generations of racial baggage.

Today, when I think clearly and honestly about my childhood mixie pride, it wasn’t just about celebrating my snowflake-unique cultural identity. There was something ugly there. To insist on being seen as mixed race allowed me to avoid being categorized as Asian. The unfair stereotype of the Chinese guy—some geeky, sexless striver who probably spent his spare time learning rote math at the Kumon on Bathurst Street—was so distasteful that I backpedalled away from it as fast as possible, never mind that none of my Chinese friends were anything like that. Back then, my answer to the “Where are you from?” question was a flurry of rhetorical attempts to distance myself from the heritage that read so obviously on my features: “I was born in Toronto and I’m fourth-generation Chinese on my mom’s side,” I would say. “She actually grew up in Don Mills and hardly even speaks Chinese. My British dad, now he’s the one who’s an immigrant.”

Kids don’t do this because they’re innately racist. They do it because there are real social advantages that come when you edge yourself a little closer to whiteness—advantages we don’t like to think about too much as adults but that are blindingly obvious to a 12-year-old.

Last September, my sister’s college friend Amanda Brewer started her first year teaching at a school in Regent Park. Brewer is the daughter of a black father and a white mother and has loose curly hair and copper skin. About once a month, an older man will casually start speaking to her in Portuguese, assuming she’s Brazilian.

The Grade 7 and 8 kids she teaches are from all over the place, many of them multiracial. Today’s 12-year-olds are keenly aware of racial subtleties that would likely be invisible to people of my mom’s generation—different shades, parental influences, subtle mixes. Living in an era of mixed races doesn’t mean the obliteration of race—it means the creation of whole new complex categories. But it also means, one hopes, that these categories cease to hold so much significance.

The second week of school, one of the girls asked Brewer a variation of the “Where are you from” question.

“Who’s white, your mom?” the student asked. “I bet it’s your mom.”

“You’re right,” Brewer told her. “My mom’s white.”

“I knew it,” the girl said, not aggressively, just matter-of-factly.

To this girl, it was clear that Brewer was culturally white. That meant her dominant parent, which to this 12-year-old meant her mother, must be white, too.

“I was amazed that she picked up on that,” says Brewer. “My students know way more about different cultures than anyone I knew growing up.” They see differences in their classmates, clock them, then take them in stride. Race isn’t invisible, but hopefully it’s just one of a litany of characteristics that inform how kids choose their friends, their dates and—who knows?—the people with whom they’ll one day have kids of their own.

Living in an era of mixed race doesn’t mean the obliteration of race—it means the creation of whole new complex categories

Is it too late to say I don’t like talking about race? It makes me uncomfortable, as it does so many other Canadians. There’s a distinctly Canadian feeling that, if we all act halfway decent and just ignore it, the race thing will more or less sort itself out. There’s also a sense, even in conscientiously liberal circles, that those who natter on about racism or “identity politics” are, if not whiners, exactly, then definitely a little tiresome. I feel it, believe me. Of all the many privileges that come with whiteness, being able to ignore race entirely is one of the most precious.

The promise of mixed-race people like my sister and me, successful enough and unencumbered by too many racial hang-ups, is an end to all that nattering. We are post-racial in the superficial sense that my friends and I—sons and daughters of Iranians and Malagasies and Russians and even Windsorites—can go out to eat dim sum or jerk chicken and make jokes about race that are actually jokes about racists. This is a lovely part of Toronto, one of the things I miss most when I’m away.

I love, too, that I have two worlds to draw on instead of one; I know what to order at dim sum restaurants and also how to make mince pies; I get Christmas and Chinese New Year’s. At times, I even like the “Where are you from?” question and the places it can lead—to conversations about my grandmother the Chinese opera singer escaping down the Yangtze, or my father’s defence of the cuisine of the British Isles. “My mother was the only Chinese hippie,” I say proudly. “This isn’t hyperbole, it’s the literal truth!”

In the future, Torontonians will produce babies in combinations the world has never seen—Yoruba-Polish-Malaysians and Estonian-Filipino-Crees popping out of hospitals across the GTA, toddling around messing with people’s neat conceptions of what race means.

A mixed-race city isn’t the same as a post-racial city, but it’s an improvement. It wasn’t so long ago, after all, that a mixed-race baby was a pariah, not cause for smug back patting. The future of Toronto is mixie.

In SouthAmerica, everybody is mixed: white with native aboriginal, white with black, native and black, white and black…etc, etc, ..In the end, everybody is mixed, come on!

I met a Japanese lady married to an Egyptian man: the result: kids looked like native SouthAmericans.

We’re all just humans. Forget the “mixie” thing…

I have to add another perspective to the conversation. I am a Canadian born Chinese in my late twenties and feel that I have had grown up in 2 worlds…the Canadian one where I feel patriotically and fiercely proud to be Canadian, but as I get older I feel increasingly connected to and interested in my heritage and proud of my family history. If we become a racial melting pot then we need to ask how do we preserve our cultural heritage. I’m not saying we should only promote same race unions but need to look at both sides of the coin. My husband is a Canadian born Korean. We are both Asian but speak to each other in English. And I can’t help but wonder about our children. They will look completely Asian. But will they be as we are? Will they care about their heritage? Or will they become ambiguously “Canadian”? I think regardless we need to hold onto our heritage in some way. We may make it our own but I think in some ways that’s what Canada has always celebrated.

I like the idea that the most important factor about race with young people, mixed or not, is what kind of food maybe found by visiting so-and-so’s house.

30% of people in Sao Paulo are mixed race. In Toronto, it’s 1.3%.

Canada and the northern hemisphere in general is 30 years late to this. Try Lima… try Sao Paulo… try Brisbane… those were post-racial cities a generation ago.

DO not present anywhere on this planet as a happy cornucopia of pples. Racism is a human problem that exists among all pple of different backgrounds and Canada is no exception! I am an ethnic person and i can tell you that i have met pple who have proudly declared that they hang only with those from their backgrounds or those who carry a superiority complex because they are of certain backgrounds or are not of certain backgrounds, those pple I’d like to issue a reminder that they too had to immigrate to Countries enriched by pple who were not ethnic and to seek a better life elsewhere! To those who speak of places like Brazil like they are racial paradises, spare me the delusions, I have heard of the hostilities shown to blacks in Brazil by those of fairer complexions, etc. And this is all across South/Central America.

as a half-east indian, half-british 33 year old, i really identified with this article. true there may be places on earth that are more open and accepting to mixed-race people, i think toronto is one of the (if not THE) the most culturally diverse and tolerant cities on the planet. the mixes of cultures we see in canada are like nowhere else- middle eastern, east asian, south asian, iranian, african, south american, first nations, metis etc. etc.

i married an egyptian and our daughter is a beautiful mix of all of our cultures :)

I found it somewhat odd that of all the kids with an East Asian background featured in the image gallery, not one had an East Asian father (this was obvious by the last names). I’m sure the ratio of mixed East Asian kids with Asian mothers as compared to Asian fathers is not 1:0 in Toronto.

I found it somewhat odd that of all the kids with an East Asian background featured in the image gallery, not one had an East Asian father.

Being a Chinese Canadian male, I do understand there is a stigma associated with Asian men in general. Studies have proven Asian males to be the least desirable during interracial dating. This has a lot to do with how Asian men are perceived in the West; usually either nerdy bookworms or punky gang members. If marriage was based purely on social economical factors, Asian men would be near the top of the list, but this isn’t the case. Look up C.N. Le’s study on this topic. Asian men do not get a fair shake when it comes to interracial dating.

This could have simply been just a photo gallery of the kids and the interviews and it would have made its point so much more effectively than the pointless, boring, overly-long soliloquay. TL is really reaching its breaking point when it comes to absolutely useless first-person features that tell us nothing (and this issue has yet another, even worse, example by the worst offender of the genre, good old Leah M!). Should have cancelled subscription ages ago — thanks for the reminder.

I liked this, I’m a melting pot myself, but my daughter looks Asian and I recall her in Costco with her Dad and I swear the 2 old ladies thought she must’ve been kidnapped (the horror!!). I arrived in time to hear the trailing end of my hubby saying..and yes the Mom is the Asian looking one.(and I’m mixed myself) .big sigh of relief on those old ladies faces LOL, but really being mixed is so last century :), it’s not a big deal.

This is ridiculous. Yes, South America has a large mixed population. It also has a large caste system (that was enforced by the law instead of culture for most of the continent’s colonial history, and that stuff lingers) based on one’s proximity to whiteness.

maybe it also has to do with the intense fetishization of east asian women. Which doesn’t bode well for young mixed asian women – burdened with all the fetishes of being asian, female and mixed-race

‘Ambiguously “Canadian”‘? Oh, the horror. What does that even mean? If they’re born to two Canadian-born parents, what else would they be? You can certainly teach them about their family history, but after a certain number of generations people will naturally feel more connected to where they’re born and where their parents were born than a distant ancestry that has no relation to their lives other than genetics. It’s natural and has been happening for thousands of years.

My children are a mix of Sri Lankan, English, Indian and Iranian. Now that is a real Mixie.

isn’t this article about 15 years too late???

and people of mixed heritage are so beautiful

I love being mixed! I was born and raised in Trinidad and all my life my parents insisted were Indian. Yah I look very Indian… but not quite..there’s something else there…and I’d argue with my parents. Before he passed away my Grandpa revealed the mix on his side..so altogether I am mixed with: Indian & maybe Bangladeshi through my Mum + Nepalese, Indian, Native Caribbean (ie Carib/Arawak/other), African & Spanish through my Dad. I was elated to discover the truth, and proud to self-identify as being mixed. I love it when people can see the black showing though I do not have definitive African features. Yay I’m a mixie! My Dad’s side has further mixed and my cousins and 2nd cousins are/will be mixed with: Portuguese; Guyanese Indian; Phillipino; Croatian; Peruvian; White American.

While I agree that there certainly appears to be an East Asian female fetish going on with some non-asian males. However, I don’t know, but highly doubt, if that fetish will translate into a long term commitment such as marriage, or even longer term with offspring. I definitely think Asia male stigma is more at play. Even some of my East Asian female friends refuse to date Asian guys. This definitely is coming from the stigma, and they might also be afraid how some of the old school Asian males treat their spouses in a domestic relationship at home, having seen it first hand.

I can understand why it would be discussed, but I don’t understand why it even matters… Just as the action of your parents do not define you, neither should their heritage… I’m not so much mixed compared to some people here, but the fact remains that although I identify myself as a 100% Iranian, I do not act, think or live like one… I do not speak like one, I’ve even been told I do not look like one because I do not “dress” like an Iranian…

So my point is, regardless of where you’re from and what you look like, you are a person, a human being, and that is all that should matter. It’s who you ARE that matters, what YOU believe and like to be…

People need to stop labelling, whether that label is social, racial or any other form there of… There are good and bad people from all over the world, so at the end of the day, it really does not matter where you’re from or what you look like! :) Know someone first, then decide who they are. Asking someone where they’re from simply means you are looking to dump a whole bunch of pre-assumptions about someone in order to make you think you know them better! To which I say : “pppffffffffff”!

Hey Craptor, interesting perspective. I’m black and totally open to dating anyone, but I’ve found Asian guys to be the least likely to approach me. I’ve heard other friends say that as well. Maybe there’s some miscommunication going on?

Just because a city has a large mxed-race population, doesn’t mean that city is post-racial. The fact that we still break these people down into the ‘parts’ that constitute them is evidence of that. Race is still an extremely important signifier in our everyday lives, and racism is still very much alive and well. We have a very long way to go.

“…promises a future where everyone is mixed.” yay?

Really… Could this writer not find anything more interesting to write about. So what if these kids are mixed. Im mixed. Super boring story and all your doing is reminding people to talk about someones race or skin colour. Please folks do you job, write about interesting ideas, motivating, sad, compelling…. But colour again. it’s been done to death.

Yes exactly biskitt…..

Thank you. Agreed.

I have quite a mixed background myself, but this was because of historic colonization in the country of my parents, so my mixture is a formula of one of types of people there – a type of homogeneity. However, I’m not even Anglo-saxon, but this Anglo factor of Canada, of Toronto, is very important and we must protect it as well, otherwise it wouldn’t be Canada anymore. My family has seen drastic changes in Toronto, make that Southern Ontario, in less than 40 years. We have to be careful here, because for years, the American media have been making race stories like this as well. This is proof that there is an agenda by the 1% to create modern mixing to get rid of anglos and caucasians/European descents, and to create more divisions and confusions (see the UK, Germany, EU countries and mass migration problem there), especially in places like Canada where ethnicity is a big part of a person and is highlighted. If there was mass modern migration to Asian countries, that would be seen as unfair and racist. Why can they be their own countries?

It’s too bad for the 1% and big business, because when all those tiring years where they pushed for “diversity”, “equality” and “tolerance”, having Anglos and Europeans and European culture around IS a part of that, because they are people too, our people. The roots of western countries and their systems come from Europeans, in our case Anglo-Saxons, with French in Quebec and some of the Maritimes. Fair is fair, and we must allow Canada to just be Canada. A part of Canada and being a true Canadian today is to know the issues, the problems and injustices, and to stand up for Canada.

Not so fast. That reason is outdated. We’ve been seeing situations, or ideas, where the later generations were actually more fiercely into their ethnic culture because of two factors: 1) the next generations find that something is missing or needed in their life, that being a farther and later generation makes them actually want to discover or preserve their ethnicity and background because they know their background is and will never be a natural people in whatever country (ie. Canada, USA); 2) the more the mass immigration or more “minorities” everywhere means there is a lack of Canadian examples or Canadian (anglo) content around, and with how Canada these days favours certain countries for immigrants (don’t be in denial here), there becomes so many of an ethnicity group(s) that it’s like being in that actual group’s country, so they naturally become associated heavily with their own ethnic group, many of them recent to Canada.

A lot of this is from historic colonization, so that mixture is a type of person there, a type of homogeneity. That’s how it is in Latin American countries, ie. Spanish with native background/mixture (called Mestizo), is a normal mixture there, almost like they are an ethnicity group. And in Latin America and former Spanish or Portuguese colonies, there is a caste system where status and levels depend on the proximity to being pure European. Ie. a purer Spanish descent, would marry someone like them, a native would be with a native, this is how it is.

Torap, it’s not surprising at all that you’d least likely be approached by an East Asian guy. Traditionally (sadly), Asians have discriminated/looked down on ethnicities of darker complexions. Even amongst the Asian countries, countries with lighter complexions (Chinese, Korean, and Japanese) for the most part have looked down on their South East Asian neighbours. While the Asians that are born or raised here, are much more open to idea of finding a partner of whatever colour, there can be inherent issues stemming from family objections to the idea of a darker complexion partner; a hassle some just don’t want to deal with. In my experience, Japanese here would be more open to the idea since their populations are pretty low, and already have mixed in with a lot of the local population. Chinese and Koreans have a massive populations here, making it easier to find partners of the same ethnicity.

The term ” mixie” is derogatory, and any person that promotes that term perhaps has emotional conflicts of identity. The term ” mixie” leaves me wishing the author had used another approach and made it less personal. Instead of trying to coin the phrase “mixie ” people should read between this author’s lines. Sorry this article is offensive and packed with blatant innuendo.

The two types of dominant mixed couples that I see are Asian women-white men (the majority now, by far) and black men-white women. The children in my daughter’s school of mixed race are largely a mix of white/asian, mostly borne by asian women and white men. I would agree, and I am not white, that whites are disappearing. The subway in the mornings is almost entireloy asian from front to back. Nary a blonde to be seen.

I hear ya! I am Chinese and my female Asian friends only want to date Caucasian/Persian guys. When I asked them why, they said they want to fix their genes (as if their genes need fixing!).

My jaw dropped when I discovered this cover story. Indeed, talking about race, as a Canadian, makes me feel extremely uncomfortable. And I’m a racialized Canadian! That cover photo, my first thought was, “Wow! Can they do that?!” I’m probably naive but perhaps if we refrain from talking about race in anything other than a jokey, lighthearted kind of way, the whole ugly business of it will just go away?

that’s not true! all my chinese male relatives including my uncles and cousins married white women!

most visibility minorities like asians and blacks

want to mix with white

they tend to look better

and it lightens their skin

from black or yellow

white and blonde are now the minority, unfortunately

Good article, however, if it was written by a “white” person I probably would not have read it. Only biracial people can speak to their experience. Only thing I found a little off-base was the fact that we are talking about “mixed” or “biracial” people like this is a new phenomenon when in fact “mixed” Race people have been here since the beginning of civilization. It only seems like something new or weird to uneducated, angry, paranoid White people. Race is a social construct and everyone is biologically “mixed”. Everyone has an ethnicity, multiple in fact. I racialize myself as biracial and I am 36 years old and from Toronto. My mother is Irish Canadian and my father is Caribbean from Trinidad. I am actually fourth generation Canadian and even have some Aboriginal ancestry. There is the “reality” (what our actually backgrounds are), and the “fantasy” (how others want to racialize you). I’m a proud biracial person and have been proud since day one. Thanks mom and dad. Oh, and my parents were both educated professionals. Another ignorant stereotype busted I guess. Toronto is a great city with a few racist bad apples like anywhere in the World.

Simply by giving the examples that all your male relatives married white women does not disprove the Asian male stigma. For your every 10 male relatives that married white women, there are probably 100 Asian females that married non-Asians. Whatever the real ratio is, it’s heavily skewed on the side of females marrying non-Asians. As others have pointed out, they’ll hear from their Asian female friends not dating Asian guys, but rarely will you hear Asian guys refusing to date Asian females. For whatever reason, the fact remains that Asian females are more desirable than Asian males when it comes to interracial dating. http://www.asian-nation.org/interracial.shtml

Wow!!! Gene therapy just by interracial dating.. is that covered by OHIP???

As an Asian man raised and lived here in Toronto all my life, from my personal

experience, the social reality is that Asian men, either born in Canada or elsewhere, are not viewed favourably and often over-looked by women in dating. Generally speaking, the presumption that Asian men are undesirable persists in the public mind. This is based on my personal account and observation. (just wanted to contribute to the discussion that’s all.)

So you’re saying that 100 years from now we’re all going to be Puerto Ricans??

LOL! Covered or not, Asian girls still flock to interracial dating anyways.

No mention of the Metis until midway through the article, and then only in passing? I know that this is an article about T-dot, but the only times in my life that I regularly had to publicly declare my racial identity (which often included a discussion of First Nations and variations thereon) were when I lived in Ontario, so I’m surprised that the Original Canadian Mixie didn’t warrant more attention.

I am a ‘mixie’ of Irish & Chippewa heritage. You would be surprised (or maybe you wouldn’t) by how many part aboriginal people there are in Toronto and Canada. Once I was out for Pub night with 5 of my IT buddies and I raised the subject: as it turned out, all 4 of the native (heh) Canadians had native blood. Only our Georgian workmate wasn’t and he was born in Tbilisi.

There already is term for people of half Asian and half Caucasian descent — those of that mixture are ‘hapas’.

Ethnicity is the phrenology of our time. Location : Earth, Milky way (like it matters!) Race does not exist. Go ahead, try to define it, I’ll wait. It’s a shame the author has to spend time explaining his “origins” to people…and that some people seem to attach importance to it! I also see some people in the comments fretting about their childrens’ lack of racial/ethnic identity or what have you. Why spend your time trying to create [illusory] division between you and the rest of the world? Wouldn’t it be better to try to tend towards an inclusive approach? I’m gunna go ahead and say it…. it seems small minded to need to belong to some type of group, be it ethnicity, nationality, or even gender. Can we move beyond the window dressing please?

Exactly ; )

So have you done anything with your life or is your racial composition how you primarily define and value yourself? Cripes.

Anthropologists will tell you that “interracial” relationships go back as early as humans have been around, since national borders change, wars happen, trade happens…as long as it hasn’t been some isolated island like Papua New Guinea (and even then), you’d be very hard-pressed to find any person who could claim “pure descent” of anything. National identities don’t have the kind of history we pretend they do. Hell, follow the silk road through Asia and you’ll find the people between South and East Asia to be a nice spectrum of “mixie” between brown and Chinese going back thousands of years (and everything in between). Nobody is “pure race”, and everyone’s mixed. We just tend to like to forget that part.

Why “unfortunately?”

what a shame for as an anglo saxon white female, i always loved the minds of many asian men i met and would have considered dating some of them, but i came of age in the 80s at a time where chinese families would not have wanted their sons to date out of their culture….

can’t agree fully with that for I am a, British, born in Toronto and my family has been traced as far back as the 11th century so I know at least where I am concerned, not having had children at all, my lineage is not mixed, not that I would care either way…but you can’t say that we all are mixed..

I want to understand what you are saying, but really it sounds like rubbish…

Lots of comments from people from Trinidad, like moi. I think ANOTHER interesting twist is that if the author visits these islands, there are large groups of NON MIXED folks there too!! now that will be interesting!

True, I am the blonde blue eyed that you speak of but now in my early 50s so when growing up here, I was a dime a dozen but now in the subway, u r right, rarely do see a blond blue eyed person……

..asked myself the same thing..

far be it for me to be a cynic, but i have met several very caucasian looking light skin and light hair female that claim to be part aboriginal if only because they don’t pay taxes and have been given other financial advantages. I was led to believe by one of them, if telling the truth, that its very easy to claim you are part aboriginal! I would hope that this is not true but it has caused me to look at very light skinned “aboriginals” and wondered if they really are, or are just taking advantage of a system by claiming so? And now you say all 4 of the “canadians” you were with also claim to be part aborginal? I have my doubts…

Ah, but you can. Tracking it back further, you’re a mix of some sort of Angle, Saxon, Jute, Norman, Old French, Roman…just like many Brits.

I see a lot of people referring to Toronto as very culturally diverse. I don’t see it. My understudying if correct is that a lot of immigrants that have and are still coming here, are often from the poorer end of the spectrum, looking for a better life. Being poorer, many don’t really live or celebrate fully, the customs of their homeland. Often, the ones that do are wealthier but they dont emigrate to Toronto but go to world class cities such as London, New York, Paris, etc and it is to those cities they seem to take their culture with them. One only has to sit in an airport in Europe, such as in London or Brussels, to see the very striking African upper classes that come through in exquisite head dresses of their nation, or the same can be said for many exceptionally wealthy Arabs you see in Europe, or Persians, Asians, etc; but never here in Canada, let alone Toronto. Each one of these people are dressed beautifully and are deeply immersed in their cultures. At least this is how it appears to someone on the “outside” looking in, therefore in Europe, or even in NYC, the cultures of each is much more prevalent but I don’t see their respective cultures here in Toronto. Therefore I see Toronto as a city with many immigrants from various cultures living here but I don’t consider this a city with any real culture behind it.

Its the same even with the British here. Rarely do you see British Aristocrats living in Toronto. They tend to stay in England or live either in Europe or years ago emigrated to Kenya or Rhodesia. The Brits one sees here for the most part are the poorer Brits looking for a better life, and those with cockney accents, or the middle class Brits who “pretend” to have been from the aristocratic class at home. There are great differences between the aristocrats and the lower classes in the ways of their own British culture. So once again, in Toronto we see the lower to middle class Brits and the aristocrats don’t emigrate here therefore we are not privvy to their culture but see the more common british foods of the lower classes here and other “customs” of their set. Please let me state that this is not a criticism of the lower or middle classes, but just a reality of which of the British people tend to emigrate here, inn order to show that we do not get the wealthier of immigrants which unfortunately deprives us of their customs. Too often the poorer immigrants are struggling to eat and get by day to day and their customs are cast by the side when trying to stay afloat any which way they can.

I am an ethnic person of a very mixed background and I wanted to another comment cause i think it is important to respond to some. I agree TORAP about Asian males and their disinclination towards darker-skin females…lol….my experience is through my ex who is Asian and Morrocan but very Canadian. He prefers darker skinned women but his mother is racist and would never be happy with him dating darker women regardless of where they are from. His lame defence of her prejudice is that SHE is more comfortable with Asian females so that is the sort of female that he should bring to their home ( his brothers have ascribed to the dictator’s wishes). He may have to as well. In a way i do feel sorry for him cause this is supposed to be a democratic society but his happiness/freedom of choice are not being respected. Why do pple like her move here anyway? We have been dating on/off for 4 yrs secretly of course…lol….I need a real MAN! Not a momma’s boy who cannot live his own life and out his own happiness first! So they can have him because he will never grow a pair! Secondly, SH, u made a comment about Parents defining u, as u can see from my comment above, i do agree that parents can dangerously try to define their own kids, but IT is up to the kids themselves to make live their own lives. They will live with the consequences if they cannot. Nowadays I prefer white males anyway! I would prefer a 50-50 mix of whites and ethnic pple in this City because considering their long history here they have created and refined this city and i do worry with all the ethnic groups here that Toronto will become a third world city, and that would make me very sad. White parents tend ti teach their kids to be considerate, polite, tolerant, manners and respect for others and what i can see of many non-white kids/parents is very lacking in any of those characteristics!

i think you are splitting hairs at this point because the “mixed Brits” you speak of, such as myself, have not experienced racist attitudes from the world at large and if anything are guilty of imposing our superiority over those of colour, mixed or not.

White people have always been the minority. It’s the main reason why race and racism exist in the first place.

So, do you think that only the wealthy are capable of having culture?

Sorry, I don’t understand. Are you making the case for Toronto ( and Canada) to stay white? Why would the 1% want to get rid of whites? And what do we need to be careful of?

We really don’t need to allow Canada to just be Canada. We need to challenge what it means to be Canadian.

OMG! There are NO parents in this article cause it’s about the kids, silly!

Or maybe racist parents/relatives are a turn-off!?!

Feel free to leave NORTH AMERICA if u don’t want your kids to blend into another culture. No one’s forcing u to stay here, remember that!

And the racial tensions are high there because of variety! Get real.

Fortunately there are plenty of other fish in the City!! Go get yourself a real man, Girlfriend! :)

Yes, but those are what makes up the British or Anglo-Saxon people or ethnic groups. That has become a culture, and homogeneity. A line is drawn at a point.

Read it again, it’s quite clear. And do some googling, not just reading what the media puts out there. Why challenge? That was done during colonial days to the post World Wars. We did already develop our form of identity that defined Canada! And we didn’t even have to have discussions all the time about it! The reason why people like you would need to question it or change is, is a result of the hoopla going on here for the past almost 30 years, confusing people or making things complex. That statement of yours is unnecessary and an insult to Canada.

Interesting you assume I am talking about ‘light skinned “aboriginals”‘ as 2 of the 4 were afro-canadian / micmaq mix from the maritimes. I am not making any “claims” about my workmates, we just happened to all have native roots in common. And none of us had had free uni. or any other advantage from our mixed blood. In fact, we all came from an era when it was a dirty secret to have ‘indian’ blood – now, of course, it’s trendy.

I still don’t understand. “That was done during colonial days to the post World Wars.” Does that mean we should give up? Was colonization a good thing? Did the 1960’s mark the start of citizens apathy? Canada is not perfect, nor will it ever be. It our responsibly as citizens to make sure we continue to strive for a more just (and equal) society.

I believe you don’t know what you are talking about. Pay a visit to Brazil and you will see way more interracial couples than any other place. Caste system in South America nowadays? You probably have no idea what is going on down there…

I am a white woman married to a black man (his mother is half white… it was extremely rare in her era to be mixed). When I had my first son in 1994 he was a novelty to alot of eyes. He got stared at constantly. I noticed a huge difference with my younger children, they were not seen as such a novelty to most people but I still get asked questions especially about my youngest who has blue eyes.

Not true! Humans are racist towards others for all kinds of reasons, white pple did not invent racism! Idiots can say whatever they want, had whites not landed here u’d have no decent place to live. i just hope Toronto does not become a third world City!

U would never dare head to American soil and be so arrogant. Canadians have developed a peaceful, very civilized society, feel free to leave if you can’t appreciate that!

Actually my reply was to jacs14, my bad!

“whites not landed here u’d have no decent place to live”

Done.

The society was founded on genocide , just like every other “white” nation outside of Europe. Who are you kidding?

Sir – you took the words right out of my mouth. We need to stop with the Identity Politics and define who we are by our beliefs and accomplishments.

Jacs14 and hubbie are both Canadian.

As long as you’ve raised your children to not be ashamed of their ethnic origins, that’s about as much as you can ask. It’s up to them to decide to what extent it makes up their personal histories and what it means to them.

When kids are young, they tend to want to fit in, and that may involve a certain amount of internalized racism if they are not strongly supported both by their family and a larger community which shows them that there is no shame in having different customs, eating different foods, speaking a different language, etc. than some of their classmates. It’s definitely easier for ethnic demographies in Toronto who have a much larger presence and established communities (complete with imported culture, foods, media, etc.) such as the Chinese community. Raising one’s kids around a larger community of similar ethnic origin can be helpful in counteracting the effects of internalized racism due to a severe dearth of Asian faces in mass media and popular culture in North America.

Also, if you haven’t already, you might want to check this out:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_culture_kid

Well, it’s an interesting statistic that WMAF (White Male – Asian Female) couplings are far more common versus AMWF, and it’s the cause of a lot of controversy in the Asian North American online community, with arguments ranging from ‘neo-colonialist’ attitudes and sexism right on down to the emasculated and desexualized depictions of Asian males in North American mass media.

More information here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interracial_marriage_in_the_United_States#Asian_and_White

Idle No More is proof positive that Canadian identity is constantly evolving, as it should, and it need not be stuck in colonial era depictions.

I’m not saying we should reject Canadian history or minimize the contributions of the Anglo- and Francophone Canadians of the past, but there does need to be a balance with bringing up the many valuable contributions to Canada made by non-white Canadians, First Nations people, etc. whose contributions have not been given the kind of exposure they deserve.

Above all, it means owning up to the mistakes of our past and trying to rectify them, as well as making positive change towards ensuring they never happen again.

I agree. I think it would behoove all Canadians, whether former-immigrants-turned-citizens or several generations Canadian, to listen to some of the absolutely gut-wrenching testimonies presented to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission by First Nations people who were forced into Indian Residential Schools.

http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=4

What’s really terrible is that for those whose school’s records were “lost”, they may well receive no compensation whatsoever, or even an apology for the suffering they endured. Forcing a person who was abused to recount their abuse and re-traumatize them all over again is bad enough, but for them to do so only to be denied even the acknowledgement that it happened to them at all, is almost as horrible as the abuse itself. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was supposed to be the process by which Canada could own up to our collective mistakes of the past, and take responsibility and ownership of that terrible systemic and racist physical and sexual abuse of First Nations people, yet to deny many of those who suffered the right to even an admission of guilt or apology for the abuse inflicted upon them just because the records were “lost” is simply unacceptable.

To me, it doesn’t matter that I was not even born when these things happened, the fact that I am a Canadian means that I implicitly benefit from the attempted genocide of First Nations peoples committed by the government of Canada, and that means I have a duty and responsibility to push our current government to right those past wrongs and to apologize and attempt redress.

We Canadians so often take pride in our peacekeeping and humanitarian efforts internationally, yet in the same breath dismiss any notions that might harm the Great Canadian Myth of our nation as being a bastion of civil rights, and we are particularly good at trying to sweep our terrible human rights record vis a vis treatment of aboriginal peoples under our collective rug.

http://ca.news.yahoo.com/blogs/dailybrew/canada-treatment-first-nations-rapped-united-nations-committee-183442188.html

If we are to be truly proud of our nation and ourselves as Canadians, we _must_ rectify the wrongs of the past as well as considerably improve our relations with First Nations peoples today. And unfortunately, despite considerable support for the Idle No More movement amongst Canadians, it has also served to bring out some of the most virulent racists amongst us.

Unfortunately, racism itself is what imposes identity politics upon marginalized groups. Articles such as these would not be necessary if racism did not exist. It is an unfortunate fact that race is still matters in this day and age, in this country, but wishing something away does not make it so. If we deny there is a problem, we will never solve the problem.

Unfortunately, it may be an example of more marginalization of First Nations peoples, and Metis people in particular.

If only. Unfortunately, ignoring a problem and wishing it would just go away does not make it go away, it just allows the problem to fester in the darkest corners of our society. It needs to be put front and centre so that we can really address the issues that are involved and put our own prejudices and misconceptions under a microscope if we are ever to find solutions to these issues.

It’s generally easier for those in a position of privilege to be entirely blind to the issues that people without that privilege must deal with on a daily basis. As a heterosexual cisgender male, I can’t speak personally to the many issues that the LGBTQ community, or women, or any other marginalized group that I am not a part of, must deal with on a daily basis, but far be it for me to deny what they go through. I may never truly know what it’s like for them, but I would hardly say that they don’t experience prejudice, discrimination, etc. and speaking about those issues in our society _is_ important. Talking about race and racism doesn’t create racism; not talking about it does, as it allows ignorance to fester.

What I find interesting is the difference between American and British soaps: American soaps are almost all predominantly white, upper class (or at least upper middle class) — think “Young & the Restless”, “Another World”, etc. — while British soaps are primarily working class / lower middle class, eg. East Enders, Coronation Street, etc. (and the British soaps are pretty good at tackling more substantive societal issues and have become much more ethnically-inclusive)

I wonder why that is, considering the United States in most other respects absolutely loves the myth of the American Dream of the poor working class boy made good via grit and bootstraps, yet their soaps are all about rich people doing absolutely nothing but terrible things to each other. Of course, this may no longer be a sustainable trend, seeing as how soap operas are going out of business in the US while reality TV is booming, by concentrating on people who are decidedly, well, not necessarily “working class” per se, but more simply “classless” people from all walks of life. I’m sure the average American working class family has way more class but you wouldn’t know it from the kind of trash that reality TV producers find to represent them. “The rich,” as Leonard Cohen put it, “have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor”. :P

Of course, I just realized the reason why the British don’t need a soap opera about the upper crust is because they actually have a 24 hour reality TV show about it, called the British Monarchy. ;) And let’s face it, East Enders is way more entertaining than what the majority of blue bloods get up to… except maybe Prince Harry. ;P

Thank you. This is one of the best articles I’ve ever read. You’re right, mixed-race is not the same as post-racial, but it’s a wonderful transformation all the same.

( Even as a 27 year old, I still haven’t stopped pointing out fellow ‘mixies’ :) )

I have wanted to say the same thing to so many of the commenters here. Celebrating race is great, but not what needs to be done. Critical examination of race and racial politics is the only way to go to make any progress.

Again, another comment which is simply proving my post! Making things more complex than it is. Go back to my comment and see the part, “….almost 30 years”. Do the math. 2013 minus 28, 29 or 30 = ?? That is safely post-war, and not long ago. If you know our history, 1967 was when Canada was now open to immigration from the rest of the world. We already developed a Canadian flavour and feel before that and overwhelmingly AFTER that period without discussing or questioning. It was just lived. Overdiscussing and overdoing it is a part of losing its essence.

Neuroantro is on the right track, but is Al probably factually correct. Unfortunately, going back to the 11th century, the Angles probably hated the Jutes, the Normans despised the Danes, the Saxes detested the Celts etc. etc.

It would seem it is not necessarily just race but some human frailty that causes us, for more than a milllenium, to stereotype and attack, rather than accept and embrace our differences.

I’ll bet you tell everyone you’re not a racist. You’re sorry Eletki doesn’t know what it means to be Canadian, but all you have is “Canada is Canada”! Pretty lame.

You didn’t really write that 1967 was when Canada was now open to immigration from the rest of the world? Plus condescension doesn’t make you right. My grandfather came to Canada from Japan in 1907. Sorry for condescending but do the math. 2013 minus 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, 106 = 1907.

I dont think we disagree. I was just trying to make the point(s) that a- Race is a fiction. Where do you draw the line? All living things are connected. Since i was a kid i always felt like if one absolutely had to create a ‘royal order’ of division it would go something like human…gender…nationality(?) But again, it is a fiction. What’s the point? As for prejudice against the LGBTQ community or any other, we have reached the moment where it has ‘flipped’ if you will, and no longer tolerated by the majority. [at least in my eyes] Its an interesting quandary about whether to ‘discuss’ these things or not. For example all the tedious talk of Obama as the first ‘black’ president. It pays homage to historical struggles on one hand, but should not be the rubric by which to judge all his actions. Was just venting my frustration at people who feel the need to ‘identify’ [divide] to make themselves feel all warm & fuzzy inside. The by product of course being the rest of humanity/creation being labelled as ‘other’. Take it easy ; )

see my comment: …”1967…We already developed a Canadian flavour and feel BEFORE THAT and overwhelmingly after.” This is mentioning the Japanese. Read carefully. Yes, Japanese, Chinese, Ukrainians were no doubt earlier minority immigrants, Canadians should know this. But read about the 1967 Immigration Act and then read my earlier points where I had alluded to 1967. Don’t post just for the sake of trying to be smart or just aiming to top people. Please read, think about the comment, research into any possible historical elements mentioned within the comment, then see if there are any possibilities of conflict or being way off the records, and then you comment with your findings or concerns.

Yeah right!

Internalized racism?…lol…what hogwash! Especially when pple bring their own racist attitudes with them who are they to talk about racism? I work for an online advertising company and one day an Asian customer from Vancouver asked us just how should they word an ad in which they wanted to indicate their preference for no members of a certain different ethnicity in their bldg! Excuse me!?! People like that do not deserve to live here with their racist attitudes and lots of ethnic groups are like that!

U need an eye-opener apparently so here goes. There may not be any Fathers of that background simply because men in that community are not allowed to date outside of their culture…lol…

Hahaha! Emasculation!?!…lol…for your information, Asian males seem to be in alot of cases governed by racist parents/relatives who object to their dating most other pples regardless of their colour! That is the situation with my Ex who is half-east asian! He needs to grow a pair. It’s men like him who live up to the notion of asian males who just not masculine enough and who are mama’s boys and not man enough to live their own lives! Pple may say it is a stereotype of males in those cultures but u know what? There is a lot of truth in it all. Hence why on earth would females of other cultures be the least bit interested anyway?

Genocide is being committed by other non-white groups for all kinds of reasons and it continues today!

Not the way of this world apparently! Kinda pathetic that it’s not but that’s human nature for you.

I think the article was very therapeutic for the author, not to mention a huge bravo in his career as he was given 10 pages of the magazine with a two page spread high gloss front cover. His experience is just that, his experience. Toronto is the most multicultural city in the world, where we are home to the most beautiful and unique blends of race in existence – this is what makes us proud.

Diversity is respect and acceptance of all that makes us unique, and individual and one thing I can say of Toronto, having been born here and carrying the torch of diversity running, we have always supported loving who you choose regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or income etc.

I think in any large metropolis you will find opposition as it is virtually impossible to have all people agree on anything – racism is also something which occurs where ever there are human beings unfortunately. Racism in Toronto has been practiced by all groups, and felt by all groups – white people included. (I imagine a few who worked hard to make Toronto what it is, including it’s diversity, immigration standards, and social policies felt quite a STING when they read the title).

I will say to everyone what I say to americans who claim all white people are racist and they want to be rid of them, if white people truly were the majority, and have worked hard to tear down walls, remove obstacles, and create an open door to embrace all others who come along regardless of race …. should they be cast in such poor light by the rest of us who benefit from their integrated beliefs, hospitable practices, and hard work?

I don’t know when my fine city reduced itself to having an old south african way of measuring people based on their racial percentages, but that isn’t the Toronto I know, it isn’t the Toronto I have ever lived in until recently, and it isn’t the Toronto the white people, or anyone else, around me exposed me to.

I am seeing more and more racism in Toronto this past decade than ever before – and it is disgusting and embarassing. It really needs to be dealt with, and I mean ALL racism even the hate speech against white people, the asian jokes, the police profiling of black males, the terrorism view of middle eastern canadians etc etc. It is ALL unacceptable no matter who says it, no matter who it is directed towards … it is not the Canada I had been so very proud of my entire life.

Pertaining to mixing races which is NOT NEW to Toronto (I promise I have a birth certificate to prove it) …. the only people who pay attention to mixes are the ones who are keeping score.

I am not keeping a race score, and never will be.

With Respect

Toronto Born and Raised and Proudly Diverse Since Birth

Hey Debs .. a novelty in 94 .. really? Where did you live??? lolol

We have biracial in our family from before the 70’s and were actively procreating throughout — and we were not the only biracial people anywhere.

Maybe the novelty was because they were so beautiful – the biracial aspect was already a done deal long before they were born … in toronto anyway! Yay Toronto!

While it is not exactly healthy to become overly codependent on helicopter parents, in the West there is a certain amount of misunderstanding of East Asian cultures where there is a tremendous emphasis on parental and elder respect, the idea of conforming to societal needs, as well as the burdens placed on males in the family and the corresponding responsibilities and duties they are charged with, which does not have an analogue in Western culture. It is foolhardy to attempt to stand in judgement of other cultures with regards to their specific customs, mores, etc. without understanding the greater cultural milieu from which they came.

What you may see as nothing more than a man being spoiled by his mother, could be seen as a man who holds his mother in the greatest of respect and who feels an intense familial and cultural pressure to live up to the duties and responsibilities charged to him as a male in the family (even more so if he is the first born, or the only male). While one may argue the inherent sexism of such a culture, the fact remains that an East Asian man who was brought up in the traditions of his culture is largely bound by them because that is all he knows, and especially amongst those East Asian families who emigrated recently, or were raised within a greater community of their own culture, will have been inculcated to those cultural mores and traditions and thus feel particularly bound to those familial ties.

I feel that you are perhaps unfairly casting aspersions on the East Asian male because of your unfortunate experience with your ex-, but I would hope that in time you will come to recognize that just because an East Asian man defers to his family’s expectations of him, that it is not necessarily due to a lack of will or flaw in character but a powerful conflict between his own personal desires and his emotional, psychological, cultural and familial ties which bind him to a set path from which he cannot easily stray.

It may not make much sense from a Western perspective but it is definitely something to take into consideration when becoming involved with any man who was not raised in Western cultural traditions. In general, it may be easier to date an East Asian man who is at least a couple generations Canadian because by then, most of those strict cultural mores and traditions would likely have faded and you will basically be dating a man of East Asian ethnicity but accultured in the Western tradition, which hopefully will reduce the cultural conflicts which can be an added stress on the relationship.

Thanks very much for getting back to me with your own comments and I do think that is his conflict ( his Mother’s beliefs vs Western ideals) but she is still being racist! There is no excusing that. It will not help with the disinclination that other females have about dating them and I have been completely turned off of dating in that culture anyway.

There’s no such thing as “post-racial”. One line from this piece that really jumped out at me was: “Of all the many privileges that come with whiteness, being able to ignore race entirely is one of the most precious.”

I am a mixie, did not offend me in the least, lighten up already!!

Well Whites are a lot less ( if at all) racist towards each other than ethnic pple are…lol…and it is so pathetic cause ethnic pple tend to originate from a lot of the worst/least desirable Countries on the planet but tend to think they are worth bragging about!

I’m sure that you intended to make some type of point with this comment. And it may have even been related to what I wrote, but it’s not immediately apparent.

“White parents tend ti teach their kids to be considerate, polite, tolerant, manners and respect for others and what i can see of many non-white kids/parents is very lacking in any of those characteristics!”

Are you being serious? Because if it’s a joke, then it’s not funny, and if it isn’t, then it’s just worrying.

yup

My partner and I do it too (and we’re in our 30s) despite the fact that she herself is mixed, as is our daughter. It’s not out of any type of malice, but rather an acknowledgment that there are more families like us out there, and there’s some comfort in that.

In an ideal world, yes. But that’s not the one that we live in. Your “racial identity” should not define who you are, but it’s beyond naive to pretend that it doesn’t have a significant bearing on how you are perceived, and indeed treated in our society.

Based on your last name, I would venture a guess that you have some experience with people making assumptions about your character, personality and aptitudes. They may even be positive ones, but assumptions nonetheless. I’m not saying that it happens all the time, or that everyone does it, but let’s be honest. The same way that many peoples’ impressions of me might be coloured (no pun intended) by my dark skin. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve walked into an interview or meeting with someone I’d only spoken to on the phone, and seen a flicker of surprise, as my appearance didn’t match what they had pictured. I’ve even been told to my face that I don’t “look like I sound”. Hopefully one day, we’ll get past it, but we’re certainly not there yet, and it doesn’t do anyone any favours to simply pretend that race isn’t still a huge factor in our society. Even in multicultural Toronto.

This is idiotic. What about white people who want to darken up a little? If only to be able to stay out in the sun a bit longer without burning.

White people are only the “minority” if you lump everyone non-white into one monolithic category, in some type of “us vs. them” exercise. Otherwise, they’re just another group in a large and diverse city. And if you have a burning need to see a lot of white people in any one place, just drive one hour outside of Toronto, in any direction. Or visit any Bay street law firm, while the partners are meeting. Or sit in on a session at Queen’s Park. Go for a walk through Rosedale or Forest Hill (Filipino nannies excepted). Or take the Queen streetcar to The Beach. Problem solved.

This is funny because I know a lot of black girls, who like asian men; but can’t get a second look because asian men find dark skin undesirable.

this is bad news. No one has a cultural identity anymore. the end is near

the world is full of mutts. No one is a pure bread anymore. Mixed race is at 69% … would not be surprised when i hear that the divorce rate is around that number as well. When the mix race was lower so was the divorce rate.

Do u take public transit?

“Whites ignore race entirely” was a part of what u said and my point is that White pple can get along alot easier with each other than ethnic pple who seem to mostly be interested in hanging with their own groups and tend to look for differences in others more so than anyone else!

First of all, I was merely agreeing with something the author wrote, which I would think is so evident that it barely even warrants mentioning. Before I start though, I was wondering exactly who are these “ethnic people” that you speak of? And are you seriously suggesting that white people in Toronto don’t also “hang out with their own groups”? I’ve read several of your posts, and I only guess that you’re interested in generating controversy with some your statements.

What the author is saying is that in our society, only white people (usually small “L” liberals) have the privilege of being able to use phrases like “post-racial”, or make statements like “I don’t even see race”. Members of visible minorities encounter situations on a daily basis that remind them of the fact that they differ in at least that one respect from the majority. I’m not saying that Toronto is Mississippi circa 1965, or that they should walk around with chips on their shoulders, but these reminders exist. And they exist every day. Television shows like “30 Rock” and more recently “Girls” have done an excellent job at examining the hypocrisy of privileged white liberals who can pretend that they “don’t see race”. When you are the only dark face in a class photo, when you can’t find a doll for your little sister that looks like her, when people casually make insensitive statements about your particular ethnic group, and then suddenly start backpedaling because they forgot that you were standing right beside them, and then trip over themselves to assure you that they didn’t mean you specifically, but “the other ones”, then you’re not allowed to ignore it. And these are situations that most white people in this part of the world simply don’t have to worry about.

I will not even bother addressing the rest of what you wrote, as I can only assume it was intended to get a rise out of myself or someone else.

Not daily anymore since I recently changed jobs, but yes, still quite regularly. And while I already know where you’re going with this, and strongly disagree in advance, I would like to see if you actually have the nerve to pursue this.

Pursue what!?! Everyone here is discussing issues stemming from what they’ve learned or from their own experiences as am I!

A rise out of you!?! Who do think you are? I don’t even know u personally! My writings like those of others here stem from my own experiences or others pple that I know. There is a tremendous amt of racism between all ethnic groups and I am having in the very office where I work, so don’t try to tell me I am talking nonsense. And if others cannot handle the truth that’s their Problem!!

My kids were the only mixed-race kids in their schools in Ottawa and only a few of a handful of Asians. Since moving to Toronto in September, my daughter who has a Chinese father (who died when she was 7) and a French-Canadian mom, marveled at all the mixed race kids in her school, telling me each day about a new combo she had met (Flipino-Polish, Irish-Japanese…) so much so that she calls one friend “White Alex” as she is the only full Caucasian in the class. She looks more Asian than her brother and would get upset when asked if she was adopted as her brother wouldn’t be asked. He likes the fact that he can pass for anything and while working at a grocery store, he would be addressed in several languages (Spanish, Portuguese). I was once asked by a stranger in a store what nationality was the father of my children which offended me, but I see that, at least in Toronto, it may become the norm.