The Ravages of Matty Matheson

A night out with the Vice Network star and Parts and Labour chef used to mean coke, whiskey by the pint and public nudity. Then, at age 29, he suffered a catastrophic heart attack

Matty Matheson drops F-bombs the way Jamie Oliver drops “Pukka tukka!,” the way Emeril Lagasse drops “Bam!” He averages roughly 150 expletives per episode on his new series, Dead Set on Life, the most of any show on the recently launched Viceland television network, which probably means the most of any show on any network, maybe ever. On each episode, Matheson visits a different community (bison ranchers in Alberta, French chefs in Hanoi, seal hunters in Nunavut), arriving bull-in-china-shop style to learn about their cultural and culinary traditions. It’s a cooking and travel show, but it’s really a vehicle for Matheson’s personality, which would be supersized even if he were the size of a chihuahua.

As it happens, he’s more of a St. Bernard—a massive dude of massive appetites. And he’s currently on the brink of massive success. Dead Set on Life started streaming online in Canada in February, but the wider television launch, in Canada and the U.S., happens this month. If all goes according to plan, he’ll be our country’s most successful culinary export since peameal bacon, our most adored jolly fat man since John Candy and our most charismatic charmer not named Trudeau.

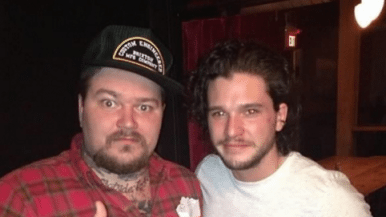

In Toronto he’s already achieved a certain level of celebrity. Pretty much anytime he leaves his Parkdale house, he’ll hear “Hey, Matty!” and he’ll try to figure out whether the person is a friend or just someone who recognizes him. There is that type of famous person you see and you think, Where do I know that guy from, again? Matheson is the exact opposite of that guy—the size, the volume, the tattoo count that is excessive even by hipster chef standards.

Maybe you know Matheson from his restaurants. He’s been the executive chef at Parts and Labour since the west-side resto–rock bar opened in 2010, and he consults on menus and marketing strategy at the Dog and Bear pub and Maker Pizza. Lately, though, it’s just as likely you’ve noticed him building his brand away from the kitchen. He interviewed Stephen Harper during a campaign stop in Whitby last fall—the only accredited press member with body ink spilling out from his collar and sleeves. Or perhaps you caught his modelling debut for Holt Renfrew in their fall 2015 campaign. There was also a recent photo shoot for the Coveteur, the style blog that generally features spindly actresses and fashion-world it girls. Inspirations for his track-pants-and-T-shirt-heavy wardrobe include ’80s wrestlers (“big guys in big gold chains”), and Eddie Murphy in Trading Places (“in the scenes where he’s still the hobo.”)

While fashion plate may be a stretch, Matheson is an undisputed “influencer,” social media speak for people who have managed to turn their existence into fruitful side gigs, if not full-time jobs. He has 101,000 followers on Instagram, which is more than double any other chef in the city. His feed is a mix of family and friends, food porn, and partying with Leonardo DiCaprio, which he did when Vice sent him to St. Barts over the 2015 Christmas holidays. Matheson’s most liked photo to date is a topless selfie with his son, Macarthur, who arrived in March—just one of dozens of #nakedselfies that, if not part of his official job description, have become integral to his success.

Haughty culinary types are loath to admit it, but Matheson could be the most relevant chef in the country right now, even though he hasn’t worked in a kitchen for over a year. Even though he hasn’t changed the way we think about food provenance like Jamie Kennedy, or topped best-restaurants lists like Rob Gentile and Susur Lee. Even though it’s unclear whether he truly is a chef anymore, or just plays one on TV.

Instead, he’s a testament to how the once humble vocation of cooking food has become a springboard for stardom. It’s not that he can’t cook. He can, and he does it well—recently at the four-day Chefs Club event in New York, put on by Food and Wine magazine, where VIP guests paid $100 a plate. It’s just that Matheson’s talent for being a chef has always been secondary to his talent for being himself, even back when that meant being Toronto’s most irrepressible party monster, which is the other place a lot of people know Matty from. Maybe you saw him chug whiskey like it was water or spent eight hours with him at an after-hours club. Or maybe you were at the New Year’s Eve party where he got wrecked and invited his friends to punch him square in the face, or you were there when he got so wasted he ripped the lighting equipment down from the ceiling and started a riot—at his own restaurant.

The title for Dead Set on Life is based on a song written by the Canadian metal band Cancer Bats. The lyrics go like this: “The day the doctor told me son, you’re gonna die / If you continue to live like this / You’ve got another year at best.” The song, as you’ve probably guessed, is about Matheson.

Early this year, Spike Jonze—the movie director who is also creative director of Viceland—came to Toronto to speak at a launch event at the Vice Media offices in Liberty Village. The TV channel is the first mainstream foray for a brand that has always taken pride in its outsider status. It’s a joint venture with the comparatively khaki Rogers Communications, who announced the $100-million partnership in the fall of 2014. The plan is to create content that is “platform agnostic,” the industry’s favourite buzz-term for programming that works on any screen. Jonze explained how at Vice, they knew almost nothing about making television, and how that was an asset. Instead, they are all about finding interesting people and pointing the camera at them. In addition to Dead Set on Life, the new lineup includes Gaycation, a travel series in which the actor Ellen Page visits international cities to check out LGBT culture; Weediquette, a show about the new world of marijuana, featuring a correspondent named Krishna Andavolu; and King of the Road, a series about extreme skateboarders. Matheson, who attended the launch, explained to the assembled media that his show is “the most anti–Food Network show I can make,” referring to the formulaic nature of most chef shows.

Vice Canada’s head of content, Patrick McGuire, has a slightly different take: “We basically just ripped off what you already see on food television. It’s just that when you put Matty in the driver’s seat, it becomes something totally different.” McGuire started working with Matheson in the spring of 2013, back when the former was a rookie producer and the latter was establishing himself as the John Belushi of the Toronto food scene. McGuire says he could have packaged any kind of show around Matheson—music, gardening, ghost hunting. “Food is what Matty fell into, but really he’s just an interesting guy who’s been through a lot and has a lot to say.” Or rather, he has a lot to shout.

The opening of every episode features Matheson delivering a monologue at peak volume. In the episode titled “The Matty of Manila,” he begins: “I’m Matty Matheson and I’m here in Winnipeg, Manitoba. You know what else is in Winnipeg? A lot of Filipinos. There’s 60,000 of these motherfuckers all over Winnipeg!” He’s not wrong—Winnipeg has the highest proportion of Filipinos of any Canadian city—but it’s the kind of thing that should sound offensive, or at least idiotic. Instead, it comes off as unscripted, honest and funny, a lot like those shows where button-cute kids answer questions from an interviewer and the audience dissolves into hysterics. Matty Matheson says the darndest things.

In another episode (titled “Pow Wow Wow”), Matheson visits the Long Plain First Nation in Portage la Prairie. The episode bounces back and forth between sincerity and hilarity. Matheson asks the chief, “When is the right time for a white guy to be wearing regalia?” The answer is that it’s okay when you’re participating in a cultural celebration. Cut to Matheson bouncing up and down in about 50 extra pounds of feathers and fringe. Like Lucille Ball crushing grapes or Chris Farley crashing through a table, Matheson is a master at using his body to get laughs. He says his appeal is pretty simple: “I’m a big guy doing funny shit.”

Matheson grew up in Fort Erie, land of bush parties and bingo halls and the Robo Mart gas station that houses what remains of his most beloved restaurant, a takeout counter that makes his favourite dish: a chicken-finger sub. His childhood home is 10 minutes away. His parents, an engineer named Stephen and a waitress named Joan, had three boys (Stephen, Matty and Adam) and a girl (Sarah). They were a close-knit and happy family—“a team,” says Matheson. Theirs was the place where all the kids gathered after school and on weekends. Matty was a class clown, king of the aforementioned bush parties, and the guy who always knew how to take a night to the next level. He was grounded a lot, but Stephen, the eldest, was considered the family handful. Matty tried cocaine for the first time in Grade 11. That same year, at a semi-formal after-party, Matty and Stephen got in a scrap with the police, during which Matty was pepper-sprayed.

Despite his status as a troublemaker, he was always popular. “Matt was friends with everyone,” says his wife, Trish Spencer, who started dating her future husband when they were in their teens. Spencer was initially reluctant, but her older sister encouraged her to go out with “the funniest guy in the world.” Their first kiss happened at a summer music festival while they were drunk and high on mushrooms. Their first proper date took place over Robo Mart tacos and subs. A year later, to celebrate their anniversary, he gave her a guitar. For their second, she learned how to play “Fade Into You” by Mazzy Star and performed it for him. That song played at their August 2014 wedding at her aunt and uncle’s house in Port Dover. Spencer, who is part-owner of the alt wedding boutique LoversLand on Ossington, wore a draped white gown and a crown of roses. Matheson wanted a lime green suit, but his bride talked him down to a more reasonable blueberry. He proposed on April Fools’ Day, yelling for Trish and pretending that he had cut his finger in the kitchen. When she ran downstairs, he was clutching a ring. (“The best part is that he didn’t even know it was April Fools’,” Spencer says). Last March, they became first-time parents. They rent a Victorian semi in Parkdale full of travel knick-knacks, records, cookbooks, framed photos and, now, baby stuff. Matheson says it’s his first place that isn’t a shithole.

He moved to Toronto in 2000 at age 19 and started as a student in Humber’s cooking program—not because being a chef was a lifelong dream, but because he wanted to live in Toronto and it was the only program in the city that accepted him. He quickly discovered a natural aptitude for butchering meat and whipping up pâtés. And he started earning good grades—80s and 90s—for the first time ever. In second year, he moved out of the dorm and into a Rexdale apartment with three roommates, or “psychopaths,” as he refers to them. More than once they spent days in the apartment, sitting around a giant mound of cocaine.

With two weeks to go before graduation, Matheson dropped out of Humber to tour Canada with a bunch of his friends who were in a metal band. He was more of a mascot than a roadie—he wasn’t allowed to help carry instruments because he was usually too drunk.

When he got back to Toronto, he started handing out resumés indiscriminately, with no grasp of the city’s culinary landscape. He got a callback from Le Sélect Bistro. A cooking school dropout would usually be relegated to dish duty, but at Le Sélect, staff rotated from station to station, which gave Matheson a chance to round out his skills. He worked closely with chef Rang Nguyen, who taught him to make classic French dishes like cassoulet and duck confit, and with whom he drank copious amounts of alcohol.

In 2006, Matheson was hired at La Palette, the Kensington Market bistro (since moved to Queen West) that was the nucleus of the restaurant industry party scene at the time. “It was Kitchen Confidential every day,” says Matheson, referring to Anthony Bourdain’s bestselling tell-all that laid bare the sex, drugs and everything else that goes on behind the scenes in the restaurant industry. Matheson would wake up around 11 a.m., get to work at noon and crack his first beer a few minutes later. The staff downed shots of cooking brandy before first service, between seatings and after close. A typical night for Matheson entailed a couple of grams of coke, 10 to 15 beers and lots of whiskey. He also frequently ate mushrooms, took MDMA, dropped acid and indulged in pretty much anything else he could get his hands on. The goal, he says, was to get as fucked up as possible.

Two years later, Matheson heard about a job opportunity—Brian Richer and Kei Ng, the creative partners behind the Canadiana design label Castor, were planning to open a restaurant called Oddfellows that would feature their offbeat furnishings. Matheson impressed his prospective bosses by cooking at a few of their dinner parties as a kind of audition, and got the job. “It was his food, but it was also I just really liked him,” says Richer, who was less impressed when his new head chef asked if they could push the opening date by a month. Matheson wanted to go on tour with his metalhead buddies. Richer sat him down and asked, “Do you want to be a roadie, or do you want to be a fucking chef?”

Matheson stayed home and helped open the small restaurant at the corner of Queen and Shaw in late summer 2008. Oddfellows was the sort of place where customers would come for dinner and stay until 3 a.m. He could always be counted on to keep the party going, spraying friends with beer when the mood struck and hosting after-after-parties in the Winnebego parked out back. “We just did whatever we wanted—it was our place,” he says. “It was like, ‘Oh, you think the music’s too loud? Then go somewhere else.’ And then I’d crank the music louder.”

Professionalism of any kind has never been Matheson’s thing. He loved to plan elaborate dishes, but he wasn’t big on nuts and bolts concerns like ingredient costing. More than once his bosses caught him taking money from the register. “It wasn’t the type of behaviour you would get away with in one of Susur’s kitchens,” says Richer. “I think if Matty had worked anywhere else, he would have been fired.” But they had grown to love him, and, just as importantly, it was Matheson who was bringing in the crowd they wanted. Rather than axing him, they brought him along on their next venture.

The plan for Parts and Labour was Oddfellows on acid—bigger, louder, crazier. Richard Lambert and Jesse Girard (the nightlife guys who were running the Social on Queen West and would soon open the Hoxton on Bathurst) came onboard as business partners, and the place was an instant it spot when it opened in the summer of 2010. The basement was a live music venue, which meant diners could often feel their table vibrating while they ate. Critics were largely positive about Matheson’s Fred Flintstone–friendly menu—his fried pig’s face (really just deep-fried headcheese) was the must-try stunt food of the season.

As much as the food, though, Matheson himself was gaining notoriety. Parts and Labour was known as “Matty’s place,” even though he had no financial stake in the business. In the winter of 2011, he threw the first annual Matty Fest, a three-day bender concert series where he was host, guest of honour and the guy most likely to get so fucked up that he forgot the entire thing. Tickets cost $10, and Matheson used the proceeds to fly in a bunch of his metalhead friends from around the country. There was ample booze, a pharmacy’s worth of narcotics and even merch (“Matty Fest”–emblazoned T-shirts, tote bags and hats).

Matheson’s antics were a constant source of conflict among his four bosses. Their meetings frequently devolved into arguments over whether to rein him in or fire him.

One night in June 2012, on the tail end of a three-day bender, Matheson clocked out from work and walked to his nearby apartment, where he flopped into bed beside Trish. He woke up around 7 a.m., several hours earlier than normal, in extreme pain. He told Trish it felt like his heart was being squeezed in a vice. She drove him to St. Joe’s hospital, where a doctor tested his enzyme levels and told Matty that he’d had a heart attack. He was 29.

When he got out of the hospital five days later, Matheson promised Trish and his employers that he was ready to change. No more drugs and no hard liquor—just beer. He stuck with it for a few weeks, and then he started changing the rules. First, it was just “no shots.” Then, three months after the heart attack, he was back to drinking and doing coke several times a week. His old dealers, who were friends, refused to sell to him, so he found different dealers. His buddies banned him from drinking in their bars, so he went elsewhere. At the Hoxton, the bouncer turned him away, so he snuck in the back. His friends found him in the basement, doing coke with people he barely knew.

Matheson was broke, desperate and covering up one lie with another. He would treat his dealers to a meal at Parts and Labour in exchange for a gram or two, then enter the meal into the computer system as comped. He would tell Trish that he was out with a friend from out of town, when really he was at an after-hours by himself. Matheson knew that many of his friends were starting to clean up their lives, but he wasn’t ready to stop. He liked being drunk and high. Plus, being Toronto’s most notorious party monster was proving beneficial to his career.

In the spring of 2013, McGuire, who had been to a few parties with Matheson, pitched him on a web series called Hangover Cures. The formula was simple. One night, he would get crazy, obnoxious, pull-your-pants-down-on-camera drunk and bring one of his Canadian chef buddies along for the ride. The next day, the chef would concoct a hangover cure at home, and Matheson would test its efficacy, often while he got smashed all over again. The product was rough, but Matheson’s onscreen magnetism was undeniable.

Around the same time, he competed on the Toronto episode of Burger Wars, a popular reality series that travels across North America holding cooking competitions. His cheeseburger won first place, and suddenly burger fans were coming to Toronto expressly to try P&L burgers and to meet the madman who made them. When chefs would visit from out of town, they made a beeline for Parts and Labour to party. For a lot of people, a heart attack in your 20s would be a wake-up call, but for Matheson, the near-death incident served to justify his crazy behaviour. “Matty thought he was indestructible,” says his friend Chris “Hambone” Hammell, who owns Town Barber on Dundas West. “He thought, I had a heart attack and that didn’t kill me. Give me more coke!”

In early November 2013, Matheson texted his drug dealer, instructing him to come to the restaurant. In the open kitchen, Matty handed over cash and pocketed a baggy of coke, in full view of customers and staff. Lambert, one of Matheson’s bosses, walked up and said, “You’re done.” He considered firing him, but two days later, Lambert contacted three of Matheson’s other close friends and decided to stage an intervention instead. Lambert says he was worried about his friend and his restaurant. “It was, ‘What are we going to do without Matty? It’s going to be sad and it’s also going to suck for our business.’ ” They summoned Matheson to Hammell’s apartment. Matheson was suspicious, since they rarely spent time there, and when he saw his closest friends, plus a guy he knew who had entered a 12-step program, he realized what was going on. Hammell says the scene was emotional: “There we were, a bunch of sketchy-looking, grown-up men, all crying. We told Matty, ‘You’ve got to stop.’”

Matheson went to his first meeting the next day. “He was definitely humouring us initially,” says Hammell. “But then something clicked. He realized how much he needed help.” Matheson says the intervention worked because he was ready, exhausted and, deep down, he was really sad.

After getting clean, Matheson called McGuire, his boss at Vice. He told him he wasn’t going to be able to get sloshed anymore, but that he was still interested in working with him. McGuire didn’t hesitate. “Matty is just a guy who is meant to be on camera. When he got sober it wasn’t a question of whether we still wanted to work with him. It was just about figuring out what we wanted to do.”

For Matheson, there was more to figure out. In the early days of being clean, his anxiety kept him up most nights. He lay in bed wondering who he was now that he wasn’t the party guy—would people still like him, would his friends still want to hang out with him, would chefs from out of town still want to party now that his pint glass was filled with club soda and he went home every night at 10? He avoided the Parts and Labour basement—the site of the infamous Matty Fest bashes. It was a while before he felt okay to return to any of his former haunts. The first time he went back to Ronnie’s Local 069—the Kensington Market dive where he once spent 15 consecutive hours partying—he felt awkward and out of place. It was even longer before he realized that most of the people who knew him were relieved to see him getting his life together: “I thought we were all partying and having fun together, but afterward there were a lot of people who told me, ‘Dude, no. You were really fucked up.’”

Matheson and McGuire came up with a new show called Keep It Canada, where Matheson would visit remote culinary communities around the country, get into adventures and then cook up a big meal. The first day of shooting was in P.E.I. in the summer of 2014. Matheson had been clean for seven months, and getting in front of the camera sober tweaked the old insecurities. “I had to adjust to the idea that I was just me, all the time,” he says. “It was great, but it was scary.”

Eventually, he learned how to summon drunk Matty as muse, and today he plays the flamboyant, unguarded goofball with ease. In a recent how-to video, he wields broccoli florets like maracas and shows his audience how to use a potato as a stress relief device. It’s not the sort of humour that holds up if you think about it for too long, but Matheson doesn’t. In real life, he is savvier, wittier and more self-aware than the guy he plays on camera. A big guy doing funny shit, sure, but he knows which shit is funny, and that’s no small thing.

Dead Set on Life is already filming a second season, which will focus a little less on food and a little more on Matheson himself, which is fine with him. “Bourdain can do whatever he wants and people will watch him because he’s Bourdain,” he says.

As for what Matheson wants, the answer is “everything.” In the space of one brief conversation, he tells me he wants to open “the sickest restaurant in Toronto,” open restaurants all over North America, never work in a kitchen again, win tons of James Beard Awards (which would require working in a kitchen), start a fashion line, be a millionaire by age 40, make television, quit making television, make a Hellmann’s mayonnaise commercial, never make a McDonald’s commercial, and just generally “do a bunch of cool shit.” It all sounds contradictory, and it is. Really, he’s just saying whatever pops into his mind in the moment. And acting on impulse has proven a pretty effective career strategy so far.

“Of course I want to be famous,” he says, his tone implying that anyone who would say differently is full of it. He knows there are “the cheffy chefs” who think he represents everything that’s wrong with the industry, but he also knows that at least a few of them have failed reality show sizzle reels collecting dust in the back of their closet. Some celebrities wear their fame with a scowl and a pair of dark sunglasses; Matheson wears his like a lime green suit.

Matty Matheson stopped drinking for the most sensible reason there is—to avoid his otherwise inevitable death. But he’s not the kind of sober person who hates on his former lifestyle. He’s not wracked with guilt and he doesn’t regret a single drug he ever did. He still blares heavy metal in his car and his kitchen; he says he still identifies as a punk kid who thinks it’s cool to wake up with a spilled ashtray on his bed. And sometimes he still misses drinking. Last fall he was in Denmark for the Mad Symposium and visited Noma, the restaurant that’s regularly named the world’s best. He ordered the tasting menu, which comes with a flight of rare wines. “Did I want the wine pairing? Of course,” he says. Instead, he had to settle for the juice, which was actually pretty delicious. “It wasn’t any of this mocktail crap.”

He isn’t big on my inclination to read his body art like a personal diary, but it’s hard to resist, given that a guy who has nearly drunk himself to death has a half-finished grim reaper tattooed on his back. The blue goose on his chest honours his beloved grandfather, a former RCMP officer who ran the Blue Goose Diner in P.E.I. The “T.S.” in a heart on his left bicep is for Trish; “Mom” and “Dad” cover his wrists, and “Sarah” for his sister is on his right ribs. The beaver defiling the pig on his right butt cheek commemorates the opening of Oddfellows, and the eagle fighting a snake on the back of his skull commemorates nothing at all. He has the initials “W.W.D.D.” on his inner right wrist, which stands for What Would Dee Dee Do? (Dee Dee Ramone, the Ramones bass player, died of a heroin overdose.) And there are a whole bunch of tattoos that reference inside jokes and favourite song lyrics. His newest addition, “Macarthur” written in simple black cursive, occupies what was, until recently, the only bit of un-inked real estate on Matheson’s chest—a tiny patch over his heart.

Parenthood, sobriety and the ever-increasing stakes of success have changed Matheson. At 34, he has started buying art for his walls, works out with a trainer three times a week and is thinking about buying an Eames chair. When he’s not on the road shooting, he spends almost all of his free time with Macarthur and Trish—they go for walks, make family ice cream expeditions—which all sounds about as punk as a Teletubbies concert, but Matheson doesn’t care. “Everything is 10,000 times better than I ever thought it would be. I love things genuinely now,” he says. And he can still be genuinely crazy when the mood strikes.

A few months ago, he was in New York for Vice upfronts, where media come to assess the new programming. After the presentation, he went to join a bunch of the Vice bigwigs for dinner at Le Bernardin, a triple-Michelin-starred restaurant that he never dreamed he’d be able to eat at. He drove over in his pickup and pulled up right outside the restaurant, which has a wall of street-level windows. He needed to change into his suit, and rather than attempting to do so in the cramped truck, he stepped onto the sidewalk and stripped down to his tighty whities, put on the suit and walked in to join his group. It was one of those amazing moments that, for Matheson, is the very definition of cool—living his life on his own terms and still getting to eat caviar that costs more than his rent. For anyone who happened to be dining at Le Bernardin that night, it’s just another crazy story to tell about Matty Matheson.

This story originally appeared in Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe, for just $29.95 a year, click here.