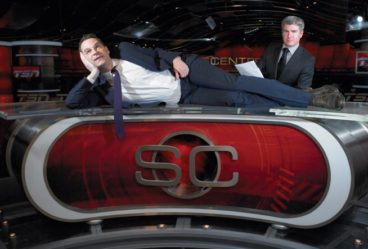

Send in the Clowns: behind the desk with SportsCentre’s Jay Onrait and Dan O’Toole

Jay Onrait and Dan O’Toole, the wildly popular, wise-cracking hosts of TSN’s SportsCentre, can’t stop laughing—at fumbling athletes, at ranting coaches and especially at their own jokes

In 2002, Jay Onrait was hired to co-host TSN’s late-night edition of SportsCentre. The broadcast, which airs after the night’s big games and matches, is the channel’s highest-profile slot. Onrait came with TV hosting experience and an encyclopedic sports mind. He was nevertheless an unusual choice: he’s a lanky joker with a background in stand-up comedy, the sort of guy who can’t resist contorting his face to make an audience laugh. He worships early David Letterman, especially his cheap gags, like when he’d chuck a watermelon off the roof. That sort of thing, he assumed, wouldn’t fly at TSN, where sports stats are analyzed with utmost seriousness.

Onrait’s boss is Mark Milliere, an executive who doesn’t suffer fools. He has a reputation for dressing down hosts who try to be funny with swift, soul-crushing concision (“This isn’t the ha-ha hut” is a typical admonition). Onrait was terrified of the man, but he wanted to get noticed: his co-host, Jennifer Hedger, was a gorgeous, porcelain-skinned blond, and competing with her for the eyes of a young male audience seemed like a losing proposition. He needed to do something. So he decided to let his personality out. Sitting at his desk in the newsroom, he wrote a script that had him chugging an entire carton of chocolate milk. It was absurd, unnecessary and unlike anything viewers had witnessed on the otherwise no-nonsense broadcast. It was also quite possibly his ticket to unemployment.

The morning after his chocolate milk stunt, Onrait checked his email, dreading the coming reprimand from Milliere. But there were only notes from friends and colleagues applauding the hilarious bit. No emails from Milliere. No calls, either. Onrait had pushed the line, and the line had moved.

Milliere soon shuffled his staff, and Hedger was moved to the 10 p.m. sports desk. Dan O’Toole, a sportscaster from Citytv Vancouver, took her place. Onrait liked him immediately. They were born only a year apart (Onrait in 1974, O’Toole in 1975) and had the same frat-boy sense of humour. They’d both grown up in small towns—Onrait in Athabasca, Alberta, and O’Toole in Peterborough, Ontario—and shared peripatetic existences as young broadcasters chasing jobs. They quickly became friends outside of work, going out for occasional drinks. Before long, O’Toole was inviting Onrait, who is single and lives in a Kensington Market condo, for dinners with his wife and two young daughters in Oshawa. On air, Onrait’s unpredictable behaviour, which could cause some co-anchors to freeze, didn’t faze O’Toole, and the more Onrait ramped it up—dropping ludicrously long pregnant pauses, talking directly to players in clips, experimenting with voices (“L.A. Dodgers” became a Kermit the Frog–inflected “L.A. Dodgerrrrrrssss”)—the more O’Toole rolled with it.

One night, during an NBA game, a San Antonio Spurs player swatted a live bat, which had somehow made its way into the stadium, out of the air with his hand. The clip was shown on sports highlights reels around the world, but no one presented it quite like Onrait and O’Toole. Viewers tuning in to SportsCentre that night watched as a paper bat, dangling from a stick held aloft by a staffer off-screen, attacked a straight-faced O’Toole while Onrait riffed about the importance of rabies shots.

Onrait and O’Toole grew bolder and more outlandish. For kicks, they decided to see if they could resist smiling while obnoxious clown music played and the cameras zoomed in on their faces (O’Toole broke first). Another time, they played a clip of a man singing the American national anthem at a baseball game in an exaggerated operatic style; after he’d wrapped up the dramatic closing note in full vibrato, the camera switched back to Onrait, who, dressed as the Phantom of the Opera, delivered a hearty rendition of Music of the Night. Last summer, during soccer’s Euro Cup, which was held in Poland and the Ukraine, they cranked the tournament’s official music—a Euro techno beat—and held a 15-second two-man dance party behind their desks.

They don’t take themselves, or their trade, too seriously. They aren’t disrespectful, but neither are they reverential toward people who run fast and hit balls with sticks for a living. In an industry where the strategy is to present clips at such a rapid pace that viewers don’t have time to even consider changing the channel, Onrait and O’Toole slam on the brakes every few minutes for a drawn-out bit of comedy, and dare viewers to stay with them. It isn’t sophisticated satire, but it works and has earned them a massive following: during an average week last fall, SportsCentre drew more than two million viewers. Their main competition, Rogers’ Sportsnet Connected, drew 101,000 in the same week; the third-place program, The Score in the Morning, drew a paltry 24,000. The Wall Street Journal recently ran a piece with the headline “Why Can’t We Have Canada’s SportsCentre?”

As Onrait and O’Toole’s stunts became more regular, so did the feedback from Milliere. He’d occasionally make requests that they tone it down, but just as often he’d congratulate them for a funny segment. Milliere realized what is now obvious: the show’s viewership was changing. Smart phones allow sports fans to watch highlights almost immediately after they happen, and from anywhere. Fans no longer need SportsCentre or its competitors to stay up to date. Onrait and O’Toole presented a solution. In the same way that viewers tune in to The Daily Show to get a little satire with their news, they would turn on SportsCentre for sports with a side of schtick.

Today, 24-hour coverage is taken for granted by Canadian sports fans. And yet it wasn’t that long ago that sports updates were relegated to the five-minute slot at the end of the nightly news. That changed in 1984, when the TV executive Gordon Craig left the CBC to launch a Canadian version of ESPN. The result, The Sports Network, based in Toronto and initially owned by the Labatt Brewing Company, later by Bell Media, enjoyed 14 profitable years as Canada’s only dedicated sports channel. Its highlights show, Sports Desk, was a simple, low-rent operation, but viewers took to it. The landscape changed again in 1998, when CTV, Rogers, Molson and Fox joined forces to launch Sportsnet. The station was aggressive from the start: before it debuted, its execs wrestled the national cable rights for NHL games from TSN. But TSN had the history, the experience and the customer base, and the ratings reflected as much. Then, in December 2011, a bombshell: Bell and Rogers, the two leading sports broadcasters, teamed up to split a 75 per cent ownership stake in Maple Leafs Sports and Entertainment, giving them control of the Leafs, Raptors, Marlies and Toronto FC.

Both Rogers and Bell had identified the same trend: despite the convenience of PVRs, no one is interested in watching the Super Bowl or game seven of the World Series a week after the fact, or even later that night. Sporting events need to be watched live. Huge advertising dollars are up for grabs—and, importantly, viewers can’t fast-forward through the commercials. If sports is the future of live television, Rogers and Bell intended to boost their stakes in the action.

In the years leading up to the MLSE purchase, TSN launched a sister channel, TSN2, and radio station, TSN1050. Rogers fired back by launching a national magazine called Sportsnet and hiring the Globe and Mail’s preeminent sportswriter, Stephen Brunt, as its back-page columnist; they added a new channel called Sportsnet One to handle extra content and another called Sportsnet World primarily for European soccer; they bought The Score and hired the city’s best sports pundits, Damien Cox, Michael Grange, Sid Seixeiro and Tim Micallef, for the radio station Fan590, and they re-signed the highly respected, hugely cranky king of sports radio, Bob McCown.

But Rogers didn’t have Onrait and O’Toole, who by this time had become two of the most-watched sportscasters in the country, and Milliere wasn’t about to lose them to a competitor. In 2010, TSN re-signed Onrait and O’Toole (“I make more than people probably think I should,” says Onrait), and began to promote them as poster boys for the brand. Once or twice a month, TSN deploys the duo to emcee galas and corporate retreats around the country. Often, the clients request Onrait and O’Toole specifically. Last September, they started the weekly, TSN-branded Jay and Dan podcast, which is mostly an extension of their oddball banter (recent topics of discussion include a dream O’Toole had about Arrested Development’s Jason Bateman and the infinite awesomeness of the Golden Girls theme song). In its first weeks, it was the most downloaded podcast on iTunes in Canada.

Every summer, TSN sends Onrait and O’Toole on the road for a 10-day televised cross-Canada broadcast. Communities that win an online contest get to play host to SportsCentre and receive $25,000 to spruce up an old rink or ballpark. In places like Clarenville, Newfoundland, and Porcupine Plain, Saskatchewan, Onrait and O’Toole are mobbed on the street, and not just by junior hockey players. Often, members of the production crew arrive to find mothers and grandmothers sitting in lawn chairs in the first row. Young women regularly claim they don’t let their boyfriends watch sports unless Onrait and O’Toole are on. The tour shows usually begin with the pair leading an audience sing-along to “Sweet Caroline” or “Don’t Stop Believing.” Onrait will often dance on the desk, his microphone held high. During the commercial breaks, they interact with the audience and drop references to local bars, sports teams and politicians (the result of much pre-event research), which drives the crowd wild.

Once, as the show ended, Onrait and O’Toole hopped off the stage and ran through the crowd to a splash pad, frolicking fully clothed in the spray, some 80 wide-eyed kids in tow.

Most kids look up to athletes, not sportscasters. Growing up, Onrait would record CNN Sports Tonight and TSN’s SportsCentre and pore over every detail—how immaculate the anchors looked in their suits, how they’d emphasize certain words, the playful way they’d recover from mistakes and how they seemed to be having so much fun. Two time zones away, growing up on his family’s pig farm, O’Toole would watch Hockey Night in Canada with the volume off and narrate the games himself. He’d practise his interviewing skills by performing both sides of the Q&A with his wrestling action figures, especially with the raspy-voiced Randy Savage.

Before landing at TSN, both took TV and radio jobs in smaller markets like Saskatoon and Fort McMurray. Of the two, Onrait is the more accomplished. He has twice been nominated for a Gemini as Canada’s best sportscaster (he won in 2011), hosted a short-lived show on MuchMoreMusic called The Week That Was and was paired with Beverly Thomson, the host of Canada AM, to co-host the morning broadcast during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. Onrait didn’t tame his humour for the new audience. In one memorable segment, CTV correspondents Seamus O’Regan and Melissa Grelo danced awkwardly in Whistler’s empty town square alongside people dressed in neon costumes; then another correspondent reported live from a dance club that contained a handful of people playing (for some reason) floor hockey. When the broadcast returned to the main desk, an amused-looking Onrait went perilously off-script: “Okay, to sum up, Bev, we had the Teletubbies dancing at Whistler, and then a nightclub with four people in it. If this is not quality morning TV, I don’t know what is.” Thomson erupted with laughter—she eventually had to hide her face behind her script—as voices off-camera cackled hysterically.

“I get asked about that clip more than anything else I’ve ever done, because so many people saw it,” says Onrait. “People can’t believe I didn’t get fired. Sure, I pushed it a bit. I was criticizing CTV on air for their coverage. But I was just saying what the viewers were thinking, and trying to make it funny. To me, that’s good TV.”

Not all of their goofing around amuses Milliere. When O’Toole called Carleton University “Last Chance U” (the clip featured Carleton’s football team) on air, Milliere made him write an apology to the school’s president; once, in response to a request from his daughter, O’Toole set her My Little Pony in front of him on the desk. Milliere’s response: “Leave your kids’ toys at home.” Onrait called Jon and Kate Plus Eight patriarch Jon Gosselin the “king of the douchebags,” and the next day CTV circulated a company-wide memo listing banned words; “douchebag” was the first.

Onrait’s caution-be-damned philosophy got the best of him during the 2012 London Games, when, dressed in a skintight Union Jack–adorned unitard, complete with a hood that covered his face, Spider-man style, he set out to conduct impromptu interviews with members of NBC’s Olympic broadcast team as they exited their cafeteria. American Idol’s Ryan Seacrest seemed game, and so did NFL commentator Al Michaels (John McEnroe wasn’t so sure: “Maybe later, buddy”), until a posse of NBC publicists swooped in and shut it down. The next day, NBC complained to CTV, calling the stunt “crazy,” and the footage didn’t air.

The SportsCentre newsroom, in the CTV-TSN broadcast centre at the 401 and McCowan, is a weird, hallucinatory place. There are no windows. Everything is made of glass or polished metal and glows or pulsates, except for the corners, which are eerily dark, making it difficult to figure out where the room actually ends. A flashing ticker of scores snakes around the room’s perimeter at eye level, and “TSN” is plastered on every free surface. There are TVs everywhere. Onrait and O’Toole sit at desks in the middle of it all. One night last October, while they prepared for a broadcast, O’Toole spat sunflower seed shells into an extra-large Tim Hortons cup, transfixed by a football game; two desks over, Onrait was occupied with late additions to his script.

O’Toole took a break from the game and, without interrupting his seed spitting, showed me his script, and then with a great flourish of his Sharpie struck out most of the text. “Meanwhile? See, I hate that. Why would they write meanwhile? It’s the same game.”

Around midnight, the other anchors and staff vacated and the mood relaxed. The grown-ups had gone home, and Jay and Dan were the only hosts left in the building. The ranking staff member was their producer, an enigmatic 40-year-old from Caledon whom I can identify only as Producer Tim—due to the blood oath I had to take with the TSN brass, who are intent on keeping his identity a secret.

The Producer Tim mystery began innocently enough. Sometime around 2005, Onrait and O’Toole, filling in on the 10 p.m. broadcast, plugged their upcoming 1 a.m. show. O’Toole pivoted in his chair and pointed at the back of the head of someone sitting at a desk in the newsroom. “Hey, Tim will be producing that show,” he said. “There he is! That guy—that’s Producer Tim!” They began to refer to him regularly, but Producer Tim refused to appear on-screen, which caused some viewers to suspect he was an invention of Onrait and O’Toole’s hyperactive imaginations. The intrigue grew. When a gang of 12-year-old boys mobbed Onrait at a Richmond Hill softball tournament recently, they all chanted the same thing: “Who is Producer Tim? Who is Producer Tim?” On Twitter, where he tweets mostly about sports trivia, Producer Tim has more than 18,000 followers (his avatar is a black silhouette with a question mark), but only a handful of people outside of TSN’s studios would be able to pick him out of a lineup.

Tim is a highly stressed person, which probably has a lot to do with chaperoning his two anchors. When Onrait has an idea for a lead-in, he must first get sign-off from Tim, and then get the rest of the team—the graphics guys, the program director—to buy in. “I’ll go into the control room and say, for example, ‘I need an image of me, Liam Neeson, Justin Bieber and a wolf,’ ” says Onrait. “These guys are used to creating schedules and scoreboards, and suddenly this idiot’s coming in and asking them to do really weird stuff. In the beginning, they weren’t thrilled, but they’ve warmed up to it.”

Before they go live, Onrait and O’Toole each crack an energy drink. And off they go. Sometimes, mistakes happen. During the taping I attended, Onrait pronounced the last name of Czech tennis player Tomáš Berdych as “Berditch,” instead of “Berdick,” and later, his Czech-speaking Twitter followers made sure he knew he’d erred. Onrait thinks it’s hilarious when his antics flop—sometimes, they’re funnier that way—but when he botches a fact or a pronunciation, he’s crushed. “Jay is the classic comedian. He’s a perfectionist,” says Onrait’s former co-anchor and good friend Jennifer Hedger. “A lot of really funny people—the Jim Carreys, the Dave Chappelles—have a darker side. He desperately wants to be awesome.”

When Onrait slides into a funk, O’Toole tries to lift his mood by sending him a photo of a model in a bikini or a funny YouTube video. “I’m like, yeah, fuck off. I know what you’re doing. And then I’ll start laughing,” says Onrait. Once, Onrait hosted an event in Quebec City called Red Bull Crashed Ice, a farcical spectacle in which regular joes skate through an ice track at dangerously high speeds. It was a sportscaster’s nightmare: the participants’ bibs were all the same colour, and Onrait had to call the race by watching a monitor instead of watching it directly. He botched his report on the first leg, badly. Panicked, he called his co-anchor for advice, and got exactly what he needed. “Who gives a fuck?” O’Toole told him. “No one cares if you don’t know this rider or that rider. They don’t even know who they’re racing against! Just do your best, then go home.”

This is a contract year for Onrait and O’Toole, who share an agent and hope to re-sign for healthy raises. Onrait has been spending his free time working on his autobiography, Anchorboy, which will be published by Wiley this November. They were recently invited by the Armed Forces to go out west and spend a day riding in fighter jets. Life is good.

Seconds after Producer Tim gave the wrap signal, the studio went dark. Writers and camera operators, their bags already packed, made a beeline for the exit. Onrait and O’Toole headed for their cars. They each got home around 2:30 a.m., still buzzing from the energy drinks and the adrenaline, and settled in front of their TVs. After a long night of watching sports, thinking about sports and talking about sports, they were aching for anything else. Lately, it’s been Breaking Bad for Onrait and American Horror Story for O’Toole. While they watch their shows into the wee hours, they text each other, sometimes about that evening’s broadcast, sometimes about their specialty: utter nonsense. Why? At that time of the night, they’re the only people they know who are still awake, and, well, they like each other.

It was worth the drive from Sarnia, ON to Port Dover, ON (and the crazy amount of rain) to meet Jay and Dan on tour. They signed autographs and took pictures with lots of soaked fans that day. They’re swell guys.

I can’t stand watching those 2 idiots. The second they are on the air, I change the channel.

If you’re critical about them, don’t hide behind anonymity. Herm Edwards said “Put your name on it”.

then why did you read this article?

jay and dan have a very funny podcast! reply if you like it too