He was a brilliant neurosurgeon. She was a beloved family doctor. Their life seemed like a fairy tale—until her body turned up in a suitcase by the Humber River. The untold story of Mohammed Shamji and Elana Fric Shamji

Elana Fric was almost never born at all. Her parents, Jo and Ana Fric, were Croatian immigrants who had settled in Windsor to take up jobs on the line at Chrysler and General Motors. After their eldest daughter, Carolina, was born in 1970, Ana suffered two miscarriages, and doctors told her she’d likely never have another child. When Elana was born in 1977, she seemed like a miracle. She grew into a precocious little girl, spending most of her free time reading.

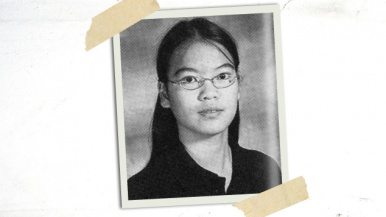

By the time Elana entered St. Anne’s high school, she was an erudite overachiever who practised Croatian dancing and worked in the cornfields outside of Windsor every summer. She was a distance runner with caramel hair, high cheekbones, a long nose, and blue eyes that squinted into crescent moons when she smiled. After a stint working a torching gun on the auto line, she came home to tell her mother that she didn’t know how her parents endured those gruelling shifts. She resolved that she would make something more of herself.

Elana had a sense of humour to match her ambition. Once, on a trip back to Croatia during high school, she boarded the plane and sat down in an empty seat in first class. When a flight attendant told her to go back to coach with her parents, she said, “Wait until I grow up—I’m going to travel first class.” In high school, she excelled in science and math, and decided she wanted to become a doctor. She recorded her evolving sensibilities in an anthology of poems she wrote during her teen years, titled It’s a Part of Life. “I am the captain of my ship,” she wrote, echoing William Ernest Henley, “navigator of my destiny.” Her poems vacillate between defiance and despair, love and fear. In “Shattered Glass,” she revealed the self-doubt that would follow her through her life: “My reflection stares / into my eyes. A useless girl / whom I despise.”

And then she fell in love. In Grade 10, Elana began dating a classmate named Matthew Renauld. They did everything together—dining with each others’ families, washing and drying the dishes side by side, going to one of Nirvana’s last live shows across the river in Detroit, even surviving a colossal traffic accident together, rolling their car five times before emerging miraculously unscathed from the wreckage. Elana and Matthew stayed together through their undergraduate years at the University of Windsor. In 1999, she began medical school at the University of Ottawa, and the couple lived in separate cities for the first time in the decade they’d been together. They continued the relationship long-distance, and were even briefly engaged, but Elana eventually broke it off. They’d grown too far apart. After she and Matthew split, she composed a painting of two white silhouettes, a man and a woman. They looked like the chalk sidewalk outlines from a murder scene come back to life, hugging, maybe dancing, with the indigo of the background spilling through the bright borders of their bodies.

One night in 2003, Elana was playing pool in a rec room at the Ottawa Hospital when a neurosurgery resident named Mohammed Shamji spotted her across the room. He asked some nurses who she was. Shamji was the son of a distinguished thoracic surgeon, Dr. Farid Shamji, who had an award named after him at the University of Ottawa’s department of surgery. A member of the Ottawa gentry, Mohammed Shamji was an academic star, a graduate of the elite Ashbury College School, and then Yale, where he completed a master’s in organic chemistry. He modelled every aspect of his life after his father: he took up distance running, just like Farid, and later followed his dad into a career in medicine, distinguishing himself at Queen’s medical school. Mohammed was shy, superior and reserved, impossibly thin, awkward and uncertain of what to do with his hands. He sometimes wore a pinched, even pained expression, as if the world had come for him while he was still bracing himself for its impact.

Elana loved to tell the story about how she barely got a second date with the man who would become her husband. After playing pool together at the hospital, Mohammed asked her to go for a drink. When they went out, she was infatuated. But he ended the evening by asking if he could set her up with his friend. He was surprised to discover later that she was interested in him at all.

In the early days of their affair, Elana was incandescently in love with Mohammed, who went by Mo. She was awed by his intellect, his ambitions, the fact that he graduated from an Ivy League college. But she sometimes felt unworthy of his love. Apparently, he agreed. Mohammed declined to speak to Toronto Life for this story, but friends say that in the beginning he didn’t take their relationship as seriously as Elana did. He continued to see a woman he knew from med school while he was dating Elana, which his colleagues thought was incongruous with his meek demeanour. Whereas Elana showered him with gifts, including a set of golf clubs, Mohammed barely made an effort to meet her friends. Many of them couldn’t understand what she saw in him. He didn’t even attend her medical school graduation; he said he was sick, but she later heard that he’d gone out with friends. Elana broke up with Mo twice within that first year, but both times he persuaded her to come back. According to one friend, he was always trying to exercise control.

In the spring of 2004, Elana brought Mohammed home to Windsor for Easter weekend. Jo and Ana Fric were unimpressed with their daughter’s new boyfriend. They found him to be aloof, almost antisocial. He would never sit with them and watch TV, or play games around the table. Jo went so far as to tell his daughter not to settle for someone he deemed so skinny and unattractive. One morning, Ana heard muffled squabbling coming through Elana’s closed door down the hall. When she entered the room and asked what was going on, she found Mohammed and her daughter, who was crying. When she asked Elana if she was alright, she told her mother: “Oh, I didn’t sleep very well.” Ana closed the door on them. She figured it was a harmless lovers’ quarrel.

A few months later, when Elana discovered she was pregnant, Mohammed found himself in an impossible position. His parents, who were Ismaili Muslims, would be furious if he had a child out of wedlock. At the same time, he was afraid to tell them that he intended to wed Elana, as they would have expected him to marry into his faith. Eventually, he decided marriage was the lesser evil, and he and Elana began planning a wedding.

Two weddings, actually. Elana and Mohammed needed multiple ceremonies to satisfy both sets of parents. They held a traditional Ismaili wedding on September 1, 2004, in Ottawa, when Elana was nearly five months pregnant. No alcohol was served, though some guests drank surreptitiously in the parking lot. At the ceremony, the class divide between their families was on display: Elana’s guests were mostly blue-collar relatives, while Mohammed’s were distinguished members of the medical community. As is customary for Muslim brides, Elana’s hands were tattooed with ornate henna, which disturbed her Christian mother.

Before the second wedding in a Catholic church, Elana and Mohammed were supposed to sit through several sessions of counselling. Mohammed refused; Elana’s friend John Mark says Mohammed asked if he’d go in his place, but Mark declined. Despite the hiccup, the couple were married at St. Francis of Assisi in Windsor, the church where Elana had been baptized, where she had received her first communion, where she was confirmed. It was a small wedding by St. Francis’s standards—there were only some 350 guests, while Elana’s sister had had 500. That was fine with Elana, who quipped: “Big weddings hide an ugly bride.” Elana bought elbow-length white gloves to cover the henna tattoos that hadn’t faded. After the ceremony, to kill time before the reception, the wedding party took a limo across town to Caesars. They walked into the casino, Mohammed in his tuxedo and Elana in her wedding gown, their lives laid out before them like a wager.

Immediately after the wedding, the couple settled into a small house on Scout Street in Ottawa. Elana began a residency in family medicine at the Ottawa Hospital, while Mohammed continued in neurosurgery. After a hard pregnancy, their daughter was born on a frigid day in January 2005. Elana was thrilled with her new baby, whose face was a perfect mixture of her parents, with her mother’s elegant nose and father’s colouring. Mohammed remained distant and withdrawn, obsessed with work.

When Mohammed would come home from the hospital, he’d often run straight upstairs to continue his studies, barely saying hello to his wife and daughter. A few weeks after the baby was born, Mohammed’s parents, grandfather, uncle and aunt came to visit. Elana was upstairs breastfeeding when the family arrived. This infuriated Mohammed, who thought it was Elana’s duty to greet her guests at the front door as a gesture of deference and respect. In front of his parents, Elana told him that she felt like she had to walk on eggshells in her own house.

Elana had known for a while that Mohammed had, as she put it euphemistically, “anger problems,” but she was proud and discreet, and she rarely disclosed to family and friends how difficult life on Scout Street was becoming. Her husband would ridicule her, sneering at her for gaining weight and calling her mother a cow. He’d push away the food she cooked for him, saying, “This is shit.”

A month after the baby was born, Mohammed called Elana’s parents in a panic. When Jo picked up, Mohammed stammered frantically: “Mr. Fric, Mr. Fric, Elana wants a divorce!” Elana took the phone from him and reassured her father: “Don’t worry, Dad—it’s nothing,” and hung up. Not long after that, as her parents were getting ready for church one Sunday, they received a phone call that they couldn’t answer in time. They dialed *69 and reconnected with the missed call. It came from the house on Scout Street. Whoever picked up the phone didn’t hang it up, and Elana’s parents listened in horror as they heard Mohammed scream: “You fucking bitch! You stupid fucking bitch!”

In the spring of 2005, Mohammed was accepted into a prestigious biomedical engineering PhD program at Duke University in North Carolina; Elana decided to take advantage of the opportunity, enrolling in the school’s master’s program in public policy. The couple prepared to move to Durham in the fall. Then, one day in May, as a brutal winter thawed into spring, their relationship turned violent. Elana later reported that Mohammed attacked her, splitting her lip in half. She took the baby and went into hiding at a friend’s condo. Mohammed started calling around, looking for them. After three days, he agreed to stay at his parents’ house if Elana would come back home. She returned to the house, but was still so afraid of her husband that she had John Mark stand guard over her for two days until her family arrived from Windsor.

Mohammed faced three criminal charges—one of assault against Elana, and two of uttering threats of bodily harm. Suddenly a man who wanted total control over his life and family had none. His true love, his career, could be ruined by his wife. With a criminal record, he might not be able to cross the border to take the PhD at Duke, and worse, he might never be able to practise medicine again. In order to save his career, he had to reconcile with Elana.

A few weeks later, Elana and her family baptized her daughter in their church in Windsor. At the party afterward, guests asked why Mohammed hadn’t attended. She told some people he was working, but confided to her cousin Rob that they’d had a dispute. He told her she didn’t have to stay with Mohammed, that she had other options, but she was resolute. She’d decided they would work it out.

And they did. On July 27, the Crown agreed to withdraw the criminal charges against Mohammed and instead had him enter into a peace bond. He recognized that his wife had reasonable grounds to fear that he would injure her, and agreed to 12 months of probation. Everything was resolved just in time for Mohammed to begin his PhD. He had his lawyer write a letter on his behalf, in case he had trouble crossing the American border. “He recently found himself embroiled in a domestic dispute with his spouse,” his lawyer wrote. “Once the prosecutor…had an opportunity to review this file and consider the version of Dr. Shamji all charges were withdrawn.”

Mohammed made it to Duke, and Elana and their daughter joined him a few months later, when she finished her residency. Her family and friends couldn’t understand why she had gone back to him. She was smart, educated, financially independent and surrounded by a devoted support network. She didn’t need him. Some friends think she was driven by ambition, that she loved Mohammed’s pedigree and the status it conferred. Others believe she was an optimist who saw brief glimpses of happiness and clung to them fiercely. She loved him, and she kept persuading herself that things would change.

In their new home, Elana and Mohammed fell into a routine. They started running marathons together, and their days began before dawn, when they’d rise to train. Afterward, Elana would drop their daughter off at daycare, and then she and Mohammed would head to their respective graduate faculties. Mohammed was the star of his department, powering through a five-year PhD in three and a half. Elana had won a rare scholarship that paid for most of her tuition, and was regarded as the leading mind in her program. After class, she’d pick up Mo and the baby, then head home to prepare dinner. On November 5, 2007, she gave birth to their second daughter.

The imbalance of the Shamji marriage struck some of their friends as strange. Elana chauffeured Mohammed just about everywhere. When her friend Valentina Nikolova asked her about it, Elana said: “Mo doesn’t really like driving.” She was responsible for everything from grocery shopping to assembling furniture to changing light bulbs. She’d go on about how brilliant Mohammed was, that she was nothing compared to him, to the bafflement of her peers, who generally regarded her as his superior. In public, she was always checking in with him, seeking his permission, deferring to him. When she was out with other people, he’d call repeatedly, demanding to know who she was with and what she was doing. Usually, she was upbeat, uncomplaining and graceful, but occasionally her classmates found her crying. “My relationship isn’t what people think it is,” she once told Valentina. “If they only knew.”

After Elana and Mohammed graduated from Duke, the family moved back to Ottawa in 2009, settling near the Ottawa Hospital. Elana started her medical practice, where she earned a reputation as a beloved family doctor. Mohammed continued his training in neurosurgery. By all accounts, his bedside manner was beyond reproach, at one point winning him a patient care award.

It was around that time that Elana and Mohammed started cultivating their social media personas. They depicted themselves as a fun-loving power couple: affectionate, jet-setting, blessed with beautiful children and showering each other in gifts. To a select few friends, however, Elana admitted that Mohammed wielded total control over her social media presence: he made her unfriend people he didn’t approve of and post only the photos he selected, stage-managing the version of their lives that was flattering to him. Mohammed controlled her at home, too. She needed to ask his permission to buy a subscription to the Globe and Mail, which he denied her. He forbade her to let their children play with kids who didn’t live up to his standards. He criticized her parenting, saying that she needed to do more and do better. He called her stupid and useless. “I should have left you,” he raved. “I would have been better off without you.”

In 2011, Mohammed went to Calgary for a year, where he was doing a fellowship at the Foothills Medical Centre in what would eventually become his specialty: spinal surgery. Elana soon discovered that he was having an affair with one of his Calgary colleagues. She found emails that confirmed it and a credit card payment Mohammed had made for him to run a race with his mistress in Calgary on Mother’s Day. When Elana confronted Mohammed, he didn’t deny it. Elana was devastated, and friends urged her to finally leave him. But still she wouldn’t. She wanted his approval, and at the same time to show him that she was his equal. She felt that she’d already invested too much in their relationship. They had two children together, a life, a home. She still loved him and desperately wanted him to love her back.

Mohammed promised to end the affair and soon he was offered his dream job, as a surgeon on Toronto Western Hospital’s neurosurgical team. He and Elana planned their move to Toronto, which meant that she would have to give up her practice. They bought a sprawling $1.5-million house in North York, and Elana took a job down the street at the Earl Bales walk-in clinic. She was understimulated. “I went through all this school and don’t want to just treat sore throats,” she told friends. A few months after their move, Mohammed said to Elana, “Why don’t we have more kids?” They had four bedrooms, and one sat empty, waiting to be filled. Mohammed wanted a boy.

Within a few months, Elana was pregnant. She hoped that the baby would be their panacea. His birth, she told friends, would be a rebirth for their marriage.

Elana and Mohammed’s son was born on an unseasonably warm day in October 2013. For close to two years after that, their relationship achieved a tenuous détente. Elana’s boss at the Earl Bales walk-in clinic, Allyson Koffman, bought a house identical in design to the Shamjis across the street, and the two women grew close. Elana’s daughters were thriving at private school, and Mohammed was busy with the job he’d worked his whole life for. He performed complex spinal surgeries, including one rare procedure called spinal cord stimulation, where an electrode was placed onto the spine and attached to a battery pack that sent therapeutic impulses into the nerves.

At Toronto Western, Mohammed earned a reputation as a miracle worker. Joseph Grossman, a lawyer who nearly died of a spinal epidural abscess before Mohammed intervened, remembers the doctor as patient and humble, making himself available to his patient whenever he was needed. Another woman met Mohammed when she was diagnosed with a brain tumour. She wasn’t a patient at Toronto Western, but a friend of a friend asked Mohammed to come by and translate the complex medical information into plain English for her family. They found him kind and accommodating, and she later became close friends with him and Elana. “They were always touching each other and complimenting each other,” she recalls. “My husband and I called them our Hollywood couple.”

In 2015, Elana moved from the walk-in clinic to a much more challenging position at the Scarborough Hospital’s family medicine unit. She also took a job as a delegate for District 11 of the Ontario Medical Association. As she began to thrive professionally, tensions between her and Mohammed reawakened. In March of 2016, the family set out on a ski trip to Vermont. They passed through Ottawa to drop their son off at Mohammed’s parents’ house. That night, Mohammed called the Frics from Ottawa, saying that Elana had badly cut her right palm, and that she was in the hospital having surgery. Elana told them that she’d done it by accident, slamming a glass down on the counter and shattering it. She told someone else she’d cut her hand while chopping vegetables, and yet another friend that a glass had broken while she was doing the dishes.

They continued on to Vermont, where they started arguing about Mohammed’s affair again. “She’s a much better lover than you,” he said. She told friends that he then started choking her. The only reason she didn’t report him in Vermont was because she was worried about what the Americans would do to a man named Mohammed.

Over the summer of 2016, the relationship vacillated between chaos and calm. The baby was with Jo and Ana for a few weeks, and the girls were at summer camp in Ottawa. Mohammed had the entire month of July off, leaving husband and wife alone in the house together. Their Facebook and Twitter profiles continued to display the cheery façade. They both started studying jiu-jitsu, and in June she posted a photo on Instagram of Mohammed in his gi with the caption: “Two-striped Dr. Mo—can break your neck and then FIX it!” A couple of months later, they celebrated their 12th—and final—anniversary. She gave him a card. On the cover were two cartoon skydivers who were returning safely to earth, hand in hand. She wrote: “My dearest Mo, I love you with all my heart. Twelve years, three children, four cities, two countries and a lifetime of memories. I can’t wait for the next 50 years.”

In real life, things were far from sunny. That fall, Elana started talking to him about divorce again. Mohammed panicked, and begged her for time to get his act together. She agreed, but her suspicions about Mohammed’s cheating persisted. When she told her friends, one of them joked that Elana should have her own affair. She did. She met another doctor who was also married with children. He was sweet and made her feel desirable again. It was the first sustained happiness she’d known since her 20s, and it emboldened her to envision a life without Mohammed.

By the end of the fall, the time she’d given her husband to turn their failing marriage around had come and gone. She confided to a lawyer that Mohammed had seriously assaulted her in October, a fact she hid from everyone else in her life. She could no longer tolerate the violence in her household. If her children had been one of the reasons why she wanted to make her marriage work before, now, she decided, she needed to get out for their sake.

In late November, she finally decided to end her marriage. Mohammed bought her a gigantic box of chocolates to try to convince her to stay. She emailed a friend on Thursday, November 24: “Sorry for being so absent these past few months. I am in the process of separating/divorcing my husband and things at home are chaotic. I will try to connect with you this weekend. I will be away at a conference.” On Friday she left for an OMA meeting that lasted until Sunday night. She spoke on panels, networked and socialized—all without Mohammed, who tweeted at her over the weekend, playing the part of the supportive husband. His final tweet to her on that Sunday read: “Congrats @ElanaFricShamji—best wishes for a successful meeting.”

When she got home from the conference on Sunday, she told those closest to her that she’d retained a lawyer and served Mohammed with divorce papers. Her lawyer wrote to him on Monday, stating that “Elana’s preference is to attempt to resolve all issues amicably and expeditiously,” and notifying him that she required his full financial disclosure. She moved into the basement, but Mohammed kept bringing her things back up into their bedroom. On Wednesday night, her mother called while Elana was giving the baby a bath. She said she had to get off the phone quickly, and Ana told her daughter to be careful. “He’s not going to do something stupid,” Elana said. She made one more call that night, to 611. It’s possible that she was trying to dial 911, and missed the first digit by millimetres.

The next morning no one could reach her. Her family called and texted throughout the day, with no response. They asked Mohammed where she was. He gave them variations of the same answer: she had left in the night with a suitcase and her boyfriend. Ana Fric panicked and asked Allyson, Elana’s neighbour and former boss, to investigate. She peeked into the garage: Elana’s Honda Pilot was still there. Allyson phoned the Frics, who called the police, packed a bag and drove through the night from Windsor to Toronto.

They arrived at 5 a.m. on Friday, and let themselves in. Two of the rugs on the main floor were missing. Ana set to work doing the dishes in the sink, and preparing crêpes for the kids’ breakfast. Leaning out of the bedroom upstairs, Mohammed, who was on the phone, didn’t come down to greet them. “Her parents are here,” Ana heard him say. A few minutes later, someone called the house, and all of the wireless phones from all over the house rang upstairs—someone had hoarded them all in the bedroom. The two older kids descended the stairs and sat silent at the table, their heads down, as their grandmother served them breakfast. Mohammed walked downstairs and into the kitchen, saying, “So you’re the ones who called the police.” Then he asked, “Are there any more of those crêpes?”

That afternoon the police found Elana. She hadn’t left with her suitcase, as Mohammed had said, but in it. She’d died of manual asphyxiation and blunt force trauma, and was then stuffed into a piece of luggage that her mother had given her. It still bore the tag from their last trip to Croatia, with the address of their ancestral town. The bag, with Elana in it, had been discarded beside the Humber River in Kleinburg. She was barefoot and dressed in her pyjamas, nearly all of her hair sliced off in ragged hacks. Her face was so swollen that Ana didn’t recognize her. Jo had to identify her, weeping. “That is my daughter.”

The next day, Mohammed Shamji was arrested at a Timothy’s coffee shop in Mississauga. Two plainclothes officers approached him at a corner table and quietly placed him in handcuffs. He now faces a charge of first-degree murder in the death of Elana Fric Shamji. As of this writing, he had yet to enter a plea. According to court filings from the Frics, he moved nearly the entirety of his family’s liquid assets, $640,000, from his professional corporation account to his lawyer’s trust account, with the note “legal fees.”

Elana’s funeral was held on December 17, at St. Francis, the Windsor church where she was baptized, confirmed and married. Her younger daughter read one of the poems Elana had written as a young woman, called “Hillside Strangers.” “We climb away on our chosen path / with only our soul as a guide….” As they await Mohammed’s trial, Ana and Jo have moved into their daughter’s house so that Elana’s children can retain as normal a life as is possible. The elder daughter, now 12, has papered her wall with her mother’s image. One morning recently, they heard Elana’s three-year-old son laughing in his room. When they went upstairs, he was standing in his bed. “Mommy was kissing me,” he giggled. He’d been dreaming.

Correction

A previous version of this story misspelled Allyson Koffman's name.