Todd Howley was an ambitious inventor with a billion-dollar idea to turn algae into fuel. When his scheme began to unravel, he snapped—and his main investor was found bludgeoned to death in the Muskoka River

Above: Todd Howley dumped Paul Maasland’s body at the Morrow Drive boat launch in Bracebridge

Todd Howley is tall, broad and bulky, with the look of a guy who was the most handsome player on his football team 30 years and 40 pounds ago. He was born in Sarnia and, after high school, spent 17 years working at Oakville’s Elliott Matsuura plant, selling and installing computerized machine tools that are used to cut steel and aluminum. Howley’s clients were the sort of energy companies he dreamed of one day owning. He was good at his job, maybe the best, but he was also condescending and obsessive, which made it hard for others to work with him. He always fancied himself the smartest person in the room and believed anyone who didn’t recognize his brilliance must be an idiot.

Howley made good money, for a long while. He lived in a large house in an upper-middle-class Oakville neighbourhood with his wife, Gina, who worked in pharmaceutical research. They had a son in 1995 and a daughter three years later. In 1999, he quit his job and started a manufacturing company called HPG, using the very equipment he once sold at Matsuura to design and build turbine blades for the energy sector. Howley’s brush with success fuelled his ambition, and he sold the company in 2005. That same year, he founded a power generation company and taught himself to engineer various technologies, like gas turbines, and hydrogen and ethanol generators. He envisioned power plants that would cost half a billion dollars each. And for the first time in his life, he was forced to rely on investors.

Over the next few years, Howley was set to partner with investment firms, renewable energy companies and tech start-ups. Each time, he says, the moneymen failed him. Early enthusiasm gave way to indifference; lucrative projects were proposed, then scuttled; and without exception, everyone would get paid but him. To lure new investors, Howley started crafting a resumé that quickly devolved into something else entirely. He itemized 28 promises that his financiers had failed to keep, including a $1.5-billion power plant project that he claimed was bungled by incompetent investors. Over time, the document swelled into a 30-page manifesto.

The Sarnia boy with the high school education kept bumping up against white-shoe money, but the windfall always eluded him. A thin-lipped smirk masked his disappointment. As Howley waited for his investors to appreciate him, he spiralled into financial peril. His lab and equipment leases came to $25,000 per month. In his personal books, he listed how much his investors still owed him: $13,000 in May 2008, $25,000 in August and $43,000 by December. “Not including my personal expenses,” Howley added each time.

But on his way to rock bottom, Howley figured out how to convert his failure into fuel: pond scum. He’d heard about a strain of algae so elegant, so simple, its potential so profound, that even the most skeptical investor would be seduced. After months of testing, he realized he could create a straightforward system of algae bioreactors that would convert carbon dioxide back into fuel. He saw a path out of debt and ignominy—and, more grandiosely, a way to save the planet. All he needed was someone to believe in him.

Howley sent his plan for the algae—and his strange manifesto—to an old business associate, Tom Wallace. The document alarmed Wallace. He’d never seen anything like it: a tirade against investors by someone looking for financing. Wallace was apprehensive, but he knew someone who might appreciate the algae technology and who could handle Howley: the angel investor Paul Maasland.

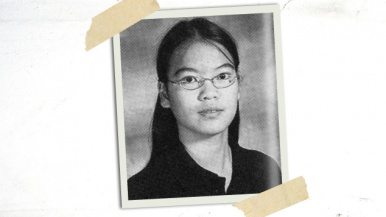

If Howley presumed that he was always the smartest person in the room, Paul Maasland usually was. Portly, bespectacled and brilliant, he was born in 1954 in Australia, to a Dutch father and an American mother. His dad was an agrarian engineer who travelled the globe advising governments on how to grow crops more scientifically. From Australia, the family moved to Iowa, Nebraska, Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Boston and finally Toronto. When he was a boy, Maasland broke his foot tobogganing. It set obtusely and gave him a turned-out waddle for the rest of his life. He didn’t complain about it; Maasland kept his emotions mostly to himself.

As a kid, he daydreamed, and read all the sci-fi and fantasy novels he could get his hands on. During a family vacation on Rhodes, his father taught him calculus, and by the time he entered Grade 9 two years later, he was well ahead of all his classmates. Maasland was a fierce competitor, handily beating all comers at pool or chess. He once played 33 moves against the chess grandmaster Boris Spassky in an exhibition match, staying alive well into the mid-game before Spassky cut him down.

After graduating from U of T with an engineering science degree in 1977, Maasland worked for Bell as a computer programmer. He liked the job but hated the bureaucracy. One night at a staff party, he boasted that he could do the work more efficiently on his own. One of his superiors overheard and hired him as an independent contractor. Maasland then founded Daedalian Systems Group, a software development firm named after the mythic Greek inventor Daedalus, in his parents’ basement.

Maasland was a heavy drinker, and for decades, he was a regular at the Yonge and St. Clair bar Jingles. Every afternoon, he’d throw back three or four double Johnnie Walker Blacks—and maybe a beer—before heading home. When he was sober, he was charismatic but shy. After a few drinks, he’d become more ebullient and affectionate, but he never slurred or spilled. Jingles is where, in the late ’80s, Maasland met his wife, Lee Stanton, a real estate agent. Stanton already had a son from a previous marriage, and Maasland didn’t want children of his own. Instead, they owned and fostered boxers. They bought shares in several dogs from a kennel in Barrie, one of which went on to win best in breed at the Westminster dog show.

The couple had a loving but unconventional marriage. Stanton divided her time between their home in London, Ontario, and her family cottage in Bracebridge. Maasland went to London on weekends and spent the rest of the time in a modest apartment on Pleasant Boulevard, down the street from Jingles. The place was essentially an office. His only decoration was a painting of two of his purebred boxers, which he left unhung in the corner of his bedroom. He didn’t even spring for a headboard.

In 2001, Daedalian employed more than 200 people, with annual revenues of $22 million. That year, Maasland sold the company to Telus. He was contractually obligated to stay on for two years, after which he went to work as a consultant for Atlantis Systems Corp. But he didn’t much like working for other people. So, in 2008, he founded a capital pool company called Verdant Financial Partners.

A capital pool company, or CPC, is the most efficient method of angel investing, a kind of cash-rich shell that exists to find a promising start-up, infuse it with capital, absorb it, then take it public. Despite its name, Verdant Financial Partners was essentially just Paul Maasland. He was its CEO and chairman of the board, running Verdant out of his apartment.

Maasland never wanted to be rich. All he wanted was to succeed at something interesting. When he learned about Howley’s algae technology, he decided it was just the investment he was looking for. Maasland met Howley at his lab, a warehouse on Wyecroft Road in Oakville, and told him on the spot that he wanted in. “It’s nothing short of an epiphany,” he later wrote.

The algae technology formed an ingenious closed-loop system, converting its waste back into fuel. When a power plant burns coal, it expels huge volumes of carbon dioxide. Howley imagined thousands of 25-gallon cylinders, each filled with algae and water and LED lights, installed in the smokestacks of coal-fired power plants. As the flue gas travelled up the smokestacks, CO2 would pass through the cylinders and into the algae, which, when combined with the light, would absorb the harmful gas, photosynthesize, grow and reproduce. This would prevent the CO2 from entering the atmosphere, and the algae’s oils could then be used as biofuel. Algae’s properties were well known in the scientific community, but Howley’s system was cheap and simple, making it a highly competitive commercial application.

For Maasland, the project harked back to the sci-fi fantasies of his youth. If it could scale, it would provide him with the financial cushion he needed to explore the other unusual investments he’d been researching, like 3-D organ printing. His one major character flaw was that he believed he could handle people and situations that were beyond his control. So he made Howley an offer: for the three companies that formed Howley’s business, Maasland would pay 360,000 Verdant shares, $200,000 over the next three years and a $120,000 salary to serve as the company’s new chief technical officer. Of course, Howley couldn’t sell the technology to anyone else without a release from Maasland, and first an independent auditor would need to test the biology—a formality, surely. Howley was interested. He had been burned by investors too many times and wanted a win. With his precious algae, he would do things his way. He agreed to Maasland’s offer. But first he needed a loan.

When Maasland transferred $30,000 into Howley’s bank account in September 2009, Howley emailed tersely, “Thanks again for your assistance with this issue.” Maasland had made it clear that the money, most of which came from his family’s trust fund, would need to be repaid. He was a generous lender, but he expected to be made whole. In fact, he was in the process of suing someone who’d failed to reimburse him for a $35,000 loan he’d made three years earlier.

A week after the cheque cleared, Howley went hat-in-hand back to Maasland. “I am now $5K from making everyone happy for the week,” he wrote. Howley claimed his equipment leases were months in arrears and his broker was demanding immediate payment. Maasland transferred another $5,000 into Howley’s account. Maasland believed in Howley; as he was cutting his cheques, he was gushing to friends, family, even his personal trainer about his company’s new acquisition.

Tom Wallace, Verdant’s CFO, was adamant that they shouldn’t negotiate with Howley—never mind lend him money—before the due diligence was completed. Maasland tried to get Howley onside, but Howley refused, claiming that he wasn’t in any position to be working for free. To alleviate some of the pressure, he filed for a Scientific Research and Experimental Development, or SRED, tax credit. He said he expected to receive $109,000, but it would take months to materialize.

By April 2010, he was desperate. Maasland asked how much he needed to borrow. Howley asked for $7,215, and Maasland wired him the money. Two weeks later, Howley was back: “The lack of resources is getting critical now that we have bill collectors (and bailiffs) at the house.” Maasland spotted him another $9,785. “I will transfer another $18,000 by early next week, bringing our total to $70,000,” Maasland wrote. “However, that is as far as I can go.”

To fund Howley and his algae project, Maasland wasn’t just drawing from his family trust. He was liquidating investments and maxing out his three lines of credit. Like Howley, Maasland was financially stretched. A decade after the Daedalian sale, Maasland had blown through much of his nest egg. He had faith in Howley, but he needed to protect himself. Maasland drew up a loan agreement for Howley, which listed as collateral Howley’s $109,000 SRED credit and “all personal assets of Todd Howley,” which included his companies and his house.

As required by the TSX, Maasland prepared a letter of intent and drew up a press release announcing Verdant’s acquisition of Howley’s three companies. Howley’s response to the draft should have been a warning: “I really do not want the attention if the names of my companies get ‘out there.’ ”

Why didn’t Howley want his companies named in the press release? Because he was in the process of signing deals with up to a dozen other investors at the same time. He’d promised all of them exclusive, proprietary rights. The investors ranged from small companies, like Midge Energy, owned by a contractor named Mike Midagliotti in Ohio, to corporations like Algaenius, a German operation that had secured funding from members of the Hapsburg family. It was preparing to launch Howley’s system on the German stock exchange.

By June, Maasland had lent Howley $105,000. It was time to test the algae bioreactors. When Howley conducted the test at his Oakville laboratory, carbon dioxide passed through the algae-filled cylinders. The algae were expected to grow and propagate at a predictable rate. Maasland had hired an exacting engineer named Michael Gainer to review the results, and he was baffled. Only one-tenth of the expected biomass was produced. Howley’s technology hadn’t just failed. It had failed spectacularly.

The failure of Howley’s first test didn’t shake Maasland’s belief in his partner. A few weeks later, he ordered Howley to ready a second round of testing. On June 29, 2010, Michael Gainer helped Howley start the test. Howley harvested the algae six hours later and sent the results to a lab for analysis. He forwarded the results to Gainer, declaring success. The algae had apparently exceeded expectations.

When Gainer reviewed the second test results, again he was dumbfounded. “Todd’s analysis does not add up,” Gainer wrote to Maasland. “What is of most concern is that Todd does not seem to be able to work his way through the simple math.” The first test failed by an order of magnitude. The second had somehow produced four times more algae than Howley had predicted. Either Howley had no idea what he was doing, or he’d cheated.

Howley didn’t like being challenged. He wrote serenely: “Paul, I fear no matter what I do for Michael, he will question the accuracy.” Then Howley used the SRED credit with which he’d collateralized Maasland’s $105,000 loan to secure yet another advance from a financing company. Before July was over, he did it again with another lender, and then used the funds from the SRED cheque to pay back even more creditors. He’d also begun shipping his bioreactors to Midge Energy in Ohio and was receiving weekly $5,000 paycheques from them. Howley had indeed invented a closed-loop system that fed itself with its own waste—not with the algae, but with the empty promise of them.

Maasland thought Gainer was overreacting. He had sunk over $100,000 into the project. He believed he could deal with Howley. And if he scrapped the deal, he’d have to get a job. He hated being an employee. He decided that to save both the algae project and Verdant itself, they would need to perform a final test. When he told Howley to ready his equipment, Howley panicked. “Let me see what I still have lying around in regards to bioreactors and algae,” he wrote.

“Don’t we still have the equipment?” Maasland asked.

“I still have most of the equipment—but it is in pieces since I have to clean it after each test.”

Suddenly Howley realized how much trouble he was in. He had only two options: succeed at the due diligence testing the way the moneymen wanted, which he might not be able to do, or repay Maasland $105,000, which he wasn’t willing to do. He knew Maasland would pursue him to the end of the earth for the money; he’d take Howley’s business, his family’s home. And critically, if he failed the third and final test, Verdant would have to issue a press release declaring his algae project a failure, and his other investors would discover his snared web of overlapping deals. He’d lose the deals he had, and his partners might very well destroy him in the lawsuits that would surely follow.

At that moment, Howley knew he had to kill Paul Maasland. Minutes after he sent that last email, he googled: “Nail gun,” “Nail gun modified,” “Nail gun massacre.” Then he told Maasland that yes, he would do the final test—he and Maasland would start it together, alone, at Howley’s laboratory, on the morning of Sunday, August 29, 2010.

The afternoon before, Maasland went to Jingles. He drank his customary double Johnnie Walker Blacks. Later, he phoned his wife at the cottage. He wanted her advice on what to do about a rash on his face. He made plans to pick up his mother and her friend the next day at 12:30 when he got back from Oakville, and take them to lunch. He fell asleep. Howley, meanwhile, took his wife and kids out for dinner at Boston Pizza. He had been preparing for weeks. He’d been googling routes to and from Bracebridge, as well as “Massland scam” and “Massland dog.” He was planning the death of a man whose name he still couldn’t spell.

The next morning, Maasland took the elevator down to the lobby of his Pleasant Boulevard apartment building. The security camera shows him wearing a black golf shirt, green khaki shorts, black shoes with high black socks—the clothes he’d be found dead in—and carrying a briefcase. He watched as the floors counted down to zero. Maasland drove his blue Subaru Forester to Oakville, arriving at Howley’s Wyecroft Road warehouse at 9:59, and waddled through the lab’s front door as the clock struck 10.

Over the next 15 minutes, Howley beat Maasland to death. He used something long and hard, like a piece of wood or a crowbar. The murder weapon was never found. Maasland had five colossal lacerations on his head that split his scalp to the bone and sent fractures branching through his skull like cracks in ice. His jaw was broken in half, as was the hyoid bone in his throat. Twelve of his ribs were fractured, and his shoulders, back and legs were bludgeoned to the colour of dusk. Maasland was beaten over nearly every inch of his body except his hands and forearms. He had no injuries that are typically called “defensive wounds.” He still believed in Howley enough not to raise his arms to protect himself.

When Howley left the lab, Maasland was unconscious but still alive. Howley knew that the business next door had two security cameras—one pointing out of its storefront and one pointed at the shared loading area in the back—but he believed the cameras were decoys to deter potential thieves. He was wrong. Footage shows that Howley drove Maasland’s blue Subaru around the corner and out of sight behind the neighbouring building. He ran back inside, and rifled through Maasland’s shorts and briefcase for his cellphone. A half-hour later, he got into his grey Ford Focus and drove up to Bracebridge. There, Howley used Maasland’s cellphone to call himself and reach his own voicemail. Howley was trying to make the cell record show that Maasland had been in Bracebridge on the day he was murdered.

A few hours later, Howley returned to his lab, by which time Maasland had died. Howley checked his email. There was an urgent message from the head of Midge Energy, his Ohio investor, who needed to speak to him immediately. With Maasland’s body next to him, Howley wrote: “Okay—no problem. Call me when you have a moment. Todd.” He returned a call he’d missed from his wife. He did not return Maasland’s missed call.

Then Howley started cleaning. Security video footage from the business next door shows him walking out of the frame with a black garbage bag. He needed to get rid of the murder weapon, his bloody clothes, and Maasland’s wallet and glasses. A few minutes later, he crossed another security camera in front of the neighbouring business wearing gloves and taking out another garbage bag, sagging with the weight of its contents.

Around 5:30, Howley left Wyecroft Road for a Home Depot a few minutes away. At the self checkout, he bought a funnel and got $100 cash back. He returned to the car and dropped off the funnel, then he turned around and walked right back in to buy the nylon rope that Maasland’s body would be found with, using the cash he’d just withdrawn. That way, the purchase wouldn’t show up on his banking records.

Howley sped back to his lab and began hosing it down. His neighbour’s security camera captured water running out from under Howley’s door and out onto the scorching concrete. A few minutes later, Howley opened the rear door. He was shirtless, wearing latex gloves, holding a rag, and he peered back and forth to see if anyone was watching. He’d miss some spots in his cleanup, and police would find Howley’s shoe print in a bit of Maasland’s blood, tiny drops of which had also splattered onto Howley’s power tools and his shoes.

Howley used the rope from Home Depot to more easily manoeuvre the weight of Maasland’s body—his chest had a deep ligature mark from the rope that the autopsy would determine was inflicted post-mortem—and when Howley was dragging Maasland’s body across the warehouse floor, it collected metal ribbons and plastic shavings from around the drill press, and a wood chip from beneath the band saw that would end up by Maasland’s belly button. They’d all be traced back to Howley’s lab.

That night, Howley’s wife and kids were returning from a barbecue in Hamilton, and Howley left the lab, with Maasland’s body still in it, for home. He spent four hours with his family and tucked his children in. At 12:30 on the morning of Monday, August 30, he returned to the scene of the crime. He retrieved Maasland’s blue Subaru, then reversed it to the large, raised loading door at the back of the building. The security camera caught him going into the warehouse to push Maasland’s body into the car, then running back out and around to the rear passenger side to pull it through the inside. Maasland’s body landed on the tote bags and plastic container that he’d kept for running errands. Howley drove through the warm Ontario darkness to Bracebridge, near Maasland’s cottage, and then dumped the body on the shore. He abandoned the Subaru in a Mississauga parking lot.

The next morning, an Ajax firefighter named Warren Johnston took his boat to the Morrow Drive boat launch, a dappled patch of gravel hedged by hawthorns and white pine, with a crooked dock that slumped into the black draft of the Muskoka. He was going fishing. The neighbourhood is a mix of cottages and year-round homes, with a school just down the street from the dock.

As he reversed his boat toward the water, he spotted what he thought was trash at the shore. He saw the lid of a plastic container, two purple grocery totes, a pair of blue latex gloves and a pair of pink ones, a white rope with freshly frayed ends, and two black garbage bags whose contents spilled onto the beach. As Johnston approached the trash to clear it, he saw sticking out from between the garbage bags what looked like a human knee.

The fact that Howley dumped Maasland’s body at the Morrow Drive boat launch just proved how little he knew the man he’d killed. Maasland didn’t much care for the family cottage—too hot, too many bugs. It was only accessible by water, but not from that launch. And he couldn’t drive the boat himself; his wife had to pick him up from the marina and pilot them to the island. He didn’t even like to swim.

Driving up from Orillia, the OPP’s forensic identification officer, Brenda Thomas, passed through the sort of summer storm that overcomes you like a mood. If the thunderhead passed over the boat launch, it could obliterate the evidence: shoe impressions and tire tracks in the soft Muskoka sand, DNA in the gloves, tiny metal and plastic shavings on Maasland’s body, the single wood chip above his navel. Thomas called for a tent. When a garbage truck travelled down Morrow Drive, she stopped it and cancelled its route. Twenty-four hours after Maasland was murdered, his watch was found under a foot of Muskoka River water. It was still running.

A few days later, an anonymous letter arrived at the Bracebridge OPP detachment. The officers had never seen anything like it. “I am writing you to inform you of my inadvertent involvement in the death of Paul,” it read. The author claims that his wood mallet was used by two unnamed women to kill Paul Maasland and goes so far as to explain their motive: dog husbandry. The women, like Maasland, loved boxers, and they’d become incensed when they heard that Maasland—whom the letter writer calls Paul Stanton, “mistaking” Paul’s last name for his wife, Lee’s—had considered withdrawing his financial support for a boxer breeding kennel in London. To get him to reconsider, the dog lovers lured him to the boat launch with the promise of a skinny dip.

Once there, they snatched Maasland’s cellphone, and threatened to call his wife and tell her that Maasland had been unfaithful unless he promised to continue to support the boxer kennel that they loved. When Maasland attacked them in a naked fit of rage, they hit him over the head, left him, and found him drowned under the dock hours later. “The reason that I am telling you this information is that the mallet can be traced back to me and since they left it at the dock I do not want to be part of the scram of threaten [sic] Paul. Paul is a pervert and his death is his own fault for attacking the girls.”

The letter is written in a kind of affected, semi-literate dialect, presumably in imitation of what its author believed the people of Bracebridge thought and sounded like. But running beneath the unusual plot is a familiar theme: the murderers were motivated by what they perceived as Maasland’s failure as an investor.

The letter also happens to contain information that only the murderer could know. The police hadn’t released the fact that there was a rope or garbage bags on the scene, and certainly hadn’t advertised the cause of death: blunt force trauma. Whoever wrote the note had killed Paul Maasland and was trying to proffer a red herring to divert the Bracebridge OPP.

It had the opposite effect. By the time the letter arrived, police had already begun investigating Todd Howley, on whose computer drafts of the anonymous note would be recovered, saved under the title “Toto1”—an inside joke intended only for its author. Howley blamed the murder of Paul Maasland on a bunch of country bumpkins, idiots killing their fickle investor idiotically. To his mind, he’d outsmarted everyone.

By killing Maasland, Howley had traded one level of scrutiny (Michael Gainer’s due diligence) for a far less forgiving lot: a half-dozen police forces, Crown attorneys, forensic accountants, coroners and DNA analysts. Through phone and email records and dozens of security cameras, they would reconstruct what Howley did after murdering Paul Maasland to divert suspicion and evade justice.

In the days that followed, the police closed in. On September 5, 2010, the OPP interviewed Howley for the first time. After his interrogation, he went back to his lab and googled “Blood removal from carpet.” The next day, detectives visited him at Wyecroft, asking for a DNA sample. He stalled them, saying he needed to speak to his lawyer. After they left, he googled “How to fool a DNA test.”

On September 18, the OPP brought in a special interviewer for Howley, Jim Smyth, the crack interrogator who had masterfully extracted former colonel Russell Williams’s confession. Smyth advised Howley that they’d be executing search warrants on his properties and vehicles. “You’re most likely going to be arrested, okay?” he said, hoping to goad Howley. “So you may want to talk to your wife about that. Maybe you want to try to get your affairs in order.” Howley didn’t crack. Instead he fled. Just before noon on September 21, he took a taxi over the Rainbow Bridge into Niagara Falls, New York, and disappeared.

Todd Howley wasn’t going to let Maasland’s murder end his dreams for the algae project. Once he reached the other side of the bridge, he met Mike Midagliotti, the contractor behind Midge Energy. Together, they would work on the algae project that might still redeem Howley. Midagliotti installed Howley in a Comfort Inn in Macedonia, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, and there, they began a large-scale test of the bioreactors. In the last few months of 2010, they were tested in a transport truck’s trailer, which was pumped full of diesel fumes. As fall turned into winter, Howley perfected the bioreactors—the algae were actually working.

Midge Energy was then contracted to install Howley’s bioreactors as a pilot project in a power generating station operated by Shaw Industries. Shaw is a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway, which is owned by Warren Buffett. The algae kept working. By April 2011, the bioreactors had been installed in the Shaw smokestack in Dalton, Georgia. And once again, the algae kept working. Howley moved to a Hampton Inn in Dalton to oversee his project.

On May 10, 2011, at four in the afternoon, driving back to his motel room from the plant, Howley knew he had done it. His algae were alive. They were thriving. They were eating the CO2 that was in the toxic air around us all. At that moment, the FBI descended upon him. They had put an electronic tracker onto his rented Jeep in Ohio and had been following him ever since. Howley had been on the run for almost eight months when the FBI apprehended him in the parking lot of the Hampton Inn. A photograph of him taken moments after his arrest shows him flashing his signature smirk.

When the FBI arrested him, he could fit all of his possessions into one small bag. He had a laptop, which he had been using to search for jobs in the Caribbean. He had four cellphones. He had a driver’s licence and passport, and his birth certificate, which time had jaundiced. He had a bottle of Advil. In a Lipton’s soup box, he had $1,500 cash. Since October he’d held onto a drawing from one of his kids, of a turkey wearing a Pilgrim’s hat with a note that said, “Happy THANKS Giving!!! ❤️ you.” A piece of paper had his wife’s name and new phone number on it. She’d had to sell the house after he ran.

Todd Howley was extradited back to Canada at the end of July, where he was prosecuted for the first-degree murder of Paul Maasland. The trial was held at Bracebridge’s 19th-century courthouse this past January. Howley’s defence was exquisitely Howley-esque. His lawyer argued, against the avalanche of evidence, that it didn’t make sense for Todd Howley to have killed Maasland and covered it up the way the Crown alleged. He was too smart for that. His jury deliberated for a single day and found him guilty. He received a life sentence, with no chance of parole for 25 years. He plans to appeal.

And yet he’s already achieved a twisted victory. His algae worked. The moneymen were proven wrong. He’d shown them. Like his algae, he took what was exhausted, wasted, spent—even the soul of Paul Maasland—and turned it into fuel.