Diehard Torontonians who’ve had it with tiny houses and giant mortgages are moving to a refuge of space, quiet and $500,000 homes. Why Hamilton is the future of Toronto real estate

Hamilton makes a terrible first impression. When you approach the city from the QEW, it doesn’t feature a skyline so much as a blockade of smokestacks—a veritable DO NOT ENTER sign made of steel and scrawled in soot. The view off the 403 isn’t much more appealing: fast-food drive-throughs, dank ’70s mid-rise buildings and five-lane one-way roads that may as well be freeways. For most of my life, I only encountered it from a safe distance, driving over the harbour on the Burlington Skyway en route to Niagara or the U.S. border. In my mind, Hamilton was to Toronto what a backyard shed is to a house—a gritty appendage, perhaps, but not a place you want to hang out.

My nose likely would’ve remained in an upturned position had I not met my future wife, Lauren, in 2005. She is a native of Dundas, the quaint valley town that officially became part of the Hamilton metropolitan area in 2001. Like many of her childhood friends, she moved to Toronto in the early aughts for work, because the job prospects in Hamilton were as grim as the scenery. Once we were officially coupled up, we’d make regular weekend trips to her parents’ place in Dundas. As our relationship evolved, so did Hamilton. I got my first glimpses of the city you don’t see from the highways: the old-school diners and antique dealers of Locke Street (the city’s mini-Roncesvalles), the indie bookstores and art-house cinema of Westdale (its micro-Annex), the cool shops and galleries sprouting up on James Street North (the West Queen West–style cultural hub), the nature trails and waterfalls lining the escarpment that bisects the city.

At the time, Hamilton was still more of an occasional weekend getaway than somewhere we wanted to live. Our social and professional lives were firmly rooted in Toronto. I was an editor at Eye Weekly (later the Grid); Lauren was planning to launch her clothing store, LAB Consignment, on Ossington. In 2008, we underwent a rite of passage for many young downtown couples: we bought a 600-square-foot starter condo in Liberty Village. Four years later, we wanted to get out of the construction-clogged, SimCity glass jungle. We put the condo up for sale and set out searching for a place where we could lay down some roots.

We lost five excruciating, exhausting bidding wars before we scored The One. It was a cute but creaky Edwardian semi in Bloorcourt. The considerable price tag—$690,000—would have normally been beyond our means, but the house was split into a pair of two-storey apartments. We rented out the lower half for $1,400, which covered half of our $2,800 monthly mortgage payment.

Once our son, Ellis, was born in 2013, the limitations of our situation—both spatially and financially—became all too apparent. We’d planned to take over the whole house one day, but we couldn’t afford a major renovation anytime soon, nor could we carry the mortgage without the rental income. Even if we sold our place at a profit, there was little hope of trading up, because every other house in the city was rising in price as well. In the stampede to get a foothold in the market, a basic truth often gets obscured: if you’re not priced out of Toronto, you’re priced in.

After becoming a mother, Lauren was done with Toronto. She felt people were becoming ruder and drivers more entitled. She routinely urged me to consider moving to Hamilton, but my Toronto pride was too deeply entrenched. The city wasn’t just where I was born and raised—it was my livelihood. I had spent my career writing about its arts and music scenes, and I couldn’t imagine living in a place where I wasn’t a five-minute walk away from noisy bars, great record stores and concert venues. I wanted to raise our son in a big-city environment, with all the cultural diversity and artistic activity it had to offer.

Not that I was taking advantage of those benefits. My weeknights were spent conked out on the couch, while weekends had become the province of park dates, playgroups and home maintenance. Once I had a kid, the minor inconveniences of downtown life became meltdown-triggering minefields. The simple act of going to a neighbourhood restaurant for lunch required a logistical calculus evaluating wait times, stroller storage space, high-chair availability and my toddler’s ticking-time-bomb temperament. The family-friendly attractions Toronto has to offer—the AGO’s Sunday kids program, the dinosaurs at the ROM, the CN Tower, the High Park cherry blossoms—came to represent lineups and headaches. And that’s to say nothing of the city’s programs, which were harder to access than Tragically Hip seats on Ticketmaster last summer.

As I entered my 40s, I was starting to question what I was really getting out of Toronto. The city was becoming the sort of place where the concept of rush hour had evolved from a daily ordeal to a perpetual state of being. Riding on claustrophobic, jam-packed subway cars had become a recurring exercise in talking myself out of panic attacks. Cycling had turned into a series of death-defying attempts to squeeze between streetcars and construction zones. I had become ever more disillusioned with the political gridlock at city hall that put transit 30 years behind where it needs to be and the vehicular gridlock that put me at least 30 minutes behind where I needed to be.

At the same time, our retreats to my in-laws’ house in Dundas were becoming less of a monthly occurrence and more of a weekly necessity—a chance to take advantage of precious grandparental child care and enjoy a rare date night. Several of Lauren’s friends had already made the move back to Hamilton, creating a built-in social circle to meet for dinners, drinks and concerts. The city was becoming more familiar and comfortable with each visit.

Suddenly, in the summer of 2014, the number one defence I always used to justify staying in Toronto—my job—was eliminated. After 14 years of working full-time, I became a freelance writer. Lauren had transitioned her bricks-and-mortar clothing store to an online-only operation. Our work was no longer tethered to the city. And so one day in 2015, when Lauren once again implored me to consider a move to Hamilton, I said yes.

For many people, the future of Toronto real estate is in Hamilton. The city has become an oasis of value and space, where properties list for roughly half of what their Toronto equivalents would, where there’s a bounty of detached houses with sprawling yards, where you can get the big-city experience at a discount. The average price of a home in the city of Hamilton is $541,720—a bargain compared to Toronto, where the average is nearing the million-dollar mark. People are buying into something you just don’t get in Oakville or Burlington: the opportunity to become part of a historic city, not a suburb, that’s undergone a dramatic grassroots transformation over the past few years. In the first quarter of 2017, 23 per cent of people who bought homes in the Hamilton area were from the GTA.

The last time Hamilton experienced this kind of boom was in the 1980s, when the city was one of the largest producers of steel in North America. At its core was Jackson Square, or Hamilton’s equivalent of the Eaton Centre, with upscale retailers, a rooftop courtyard and a massive flow of shoppers. The downtown blossomed. New office towers arrived, along with a farmers’ market, a hotel and the $35-million Copps Coliseum. But the double whammy of the early ’90s recession and global outsourcing shrank the local manufacturing sector. Thousands of jobs were lost in the ’90s, as the steel titans Stelco and Dofasco declined, and the Firestone Tire factory and Otis elevator plant shuttered. The economic aftershocks hollowed out the core. The Ontario government tried to stem the tide by appending Jackson Square with a new addition, but it was a spectacular failure. The mall’s big retailers moved out, bargain stores moved in, and the once-proud emblem of Hamilton’s future had devolved into a brutalist block covered in pigeon poop.

Writing this story, I spoke to several Hamiltonians who witnessed the city’s decline. One of them was Mark Milne, a former indie rocker who co-founded the independent record label Sonic Unyon. In 1997, his company needed a larger space to accommodate its growing distribution business. One day, a man approached Milne, asking him to take a three-storey, 14,000-square-foot warehouse building off his hands. “I was like, ‘We can’t afford a building. We’re barely getting by!’ ” says Milne. The man replied, “You can have it for a year for free.” The building had been abandoned for three years. “He just said, ‘Turn the lights on, turn the heat on, just keep it alive for me.’ ” The third floor had pigeons living in it, there was no heat and the roof was collapsing. “It was disgusting,” he says. After the year of free rent had passed, Sonic Unyon was able to buy the building for cheap.

At the time, city councillors were afraid Hamilton would go the way of U.S. Rust Belt cities like Buffalo, Flint and Detroit. So, in the early 2000s, the city devised a strategy to turn the downtown around. To attract real estate speculators and build up the desolate tundra, the city eliminated development charges for new builds, established a loan program for residential construction and helped fund makeovers for abandoned buildings. It took a few years, but by the mid-2000s, the downtown was flourishing.

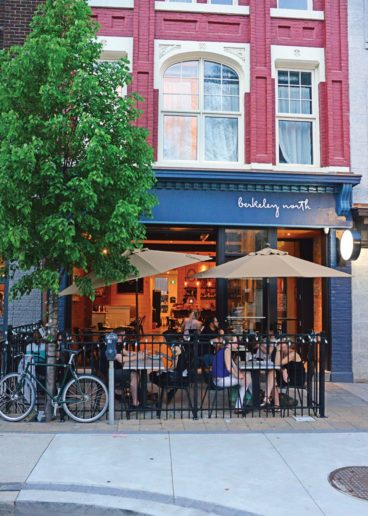

The grungy thoroughfare of James Street North was one of the first stretches to benefit from the revamp. Thanks to upstart businesses like the art supply store Mixed Media, James transformed into a lively pedestrian-friendly boulevard. Soon, a handful of local businesses banded together for Art Crawl, a festival where all the galleries, stores and restaurants on the strip stayed open late and blared music onto the street. Art Crawl did for James Street what the Drake Hotel did for Queen West: thousands of people were soon showing up for monthly street gatherings. (Supercrawl, a massive annual spinoff festival, was launched in 2009.) Over the next few years, more hip new spots materialized along the strip, like the café-cantina the Brain, the retro diner Jack and Lois, and the vintage furniture store Chaises Musicales. Even lowly Jackson Square was soon glowing with fresh signs of life: its current tenants include a satellite McMaster University campus, a busy Nations Fresh Foods supermarket and a new LCBO.

Much like that moment in the mid-2000s when proud Torontonians started wearing subway station pins and neighbourhood tuques, Hamiltonians have turned their new civic pride into a cottage industry. At Mixed Media, you can purchase artistically rendered survey maps of local neighbourhoods. Online, urban bloggers, city councillors and even Mayor Fred Eisenberger broadcast their message using the #HamOnt hashtag, which has become the city’s unofficial news feed (and has naturally spawned its own T-shirt logo: an illustration of a baked ham embossed with the letters ONT).

Hamilton is just getting started. These days, the city’s top employers aren’t the steel mills, but McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences Corp., the umbrella organization for the hospital network. The Hamilton area is expected to generate 2,600 new jobs in 2017 and 4,000 more next year, mostly in the tech, health and education sectors. As the economy has grown, so has the city’s infrastructure. A second GO station opened in 2015. Along King Street, the historic Royal Connaught hotel has been revived as a condo complex, and the once-neglected Gore Park is now a lavish public square. Despite some heated 11th-hour resistance from pro-car councillors, the city will proceed with a crosstown LRT line. The West Harbour is about to undergo a $143-million, Port Lands–style facelift. Between 2009 and 2013, 500 condo units were built downtown; in the last two years, that number ballooned to 1,300. The city has brought some of its many block-long parking lots to market to attract developers. Hamilton has always had the sturdy bones of a metropolis. Now it’s flexing the will to flesh them out.

In August 2015, Lauren and I started coming into Hamilton regularly on weekends for open houses. At a time when semis in Toronto were getting bids into the seven figures, we were blown away by what you could find in Hamilton for under $500,000. There was one cottage-style place in Dundas with gorgeous hardwood floors and a modern kitchen with a vaulted ceiling (it also had a separate cellar that looked like something out of The Silence of the Lambs). Another, in the west end, had an amazing covered outdoor deck that could have been a restaurant patio.

That November, we discovered a 100-year-old, Queen Anne–style home in Kirkendall, a Leslievillian downtown neighbourhood filled with regal Victorian houses and charming worker’s cottages. The place had all the practical features we could only dream of in Toronto—it was a detached three-storey with three bedrooms, three bathrooms, a big backyard in which the kid could run wild and quadruple the living space of our Bloorcourt unit. It also had some cool quirks, like a spiral staircase ascending out of the master bedroom into a finished studio attic I could use as an office space, and elaborately detailed built-in bookshelves. There were five parks within a 10-minute walk, daycare options and a great elementary school a few blocks away. The price: $499,900.

We felt so good about the place that we immediately ordered an inspection and then, satisfied with the results, submitted a bid at asking. There was no scheduled offer night, no sitting in the car for three hours outside the house, no realtor to inform us that we needed to go higher. Our agent simply phoned in the offer and called us a few hours later to tell us the house was ours.

Hamilton was good for us because Toronto was good to us. During our four years in Bloorcourt, the Toronto market had continued its gravity-defying act, and we were able to sell our place for $845,000—which, after clearing up debts, left us with enough for a 20 per cent down payment and a monthly mortgage equivalent to the $1,400 share we were paying in Toronto. We were able to buy into one of Hamilton’s nicer neighbourhoods: our house is a short walk to the shops and restaurants of Locke Street, footsteps from the bike and hiking trails at the base of the Niagara Escarpment, and close to the 403 for drives back into Toronto to see my mom and friends. Though we still live paycheque to paycheque, we have a little more budgetary breathing room, thanks to cheaper daycare, insurance and utilities.

I never planned to be a daily commuter. At the time of our move, I was working primarily on short-term contracts as a producer for CBC Radio. I figured I would take the GO train in to cover those limited shifts. But as my schedule at CBC filled in to cover much of 2016, I became a full-fledged, card-carrying member of the Presto pack.

In Toronto, a subway ride from Ossington station to Union could be a 45-minute ordeal—three packed trains might pass before I could squeeze onto one, and once I did, there was barely enough room to hold open a book. The train ride between Toronto and Hamilton was long (75 minutes) and expensive ($10.75 each way), but it was predictable and relatively stress-free. Since Hamilton is the first stop on the Lakeshore West line, the 6:48 was practically empty when I boarded each morning, so I was guaranteed a seat. The trip went by fast if I put the time to productive use—I typed this sentence as my train rolled out of Oakville.

After my contract at CBC ended in the spring, I began freelancing full-time from home, disabled my phone’s six a.m. alarm and got to know my new hometown. It’s taken some time to realize I’m no longer a Torontonian. Moving to Hamilton has given me a new appreciation for Toronto’s quilt-like assemblage of communities, where I could walk from Parkdale to the Danforth and always be in a lively, intimate streetscape. Even though Hamilton is much smaller than Toronto, it’s more sprawling and harder to navigate: in the lower city, the pedestrian-friendly districts are separated by long tracts of residential streets, sparse big-boxes and boarded-up retail.

Hamilton was designed to whisk motorists across town as quickly as possible, and our family has become more auto-dependent as a result. In Bloorcourt, we had an abundance of health food stores, fruit stands and butchers at our doorstep; now we get in the car and head to the nearest Fortino’s. Where we used to hop down to the College Street YMCA for some indoor play time on a winter day, now we drive over to Burlington and enter that parental twilight zone known as the suburban industrial-park jungle gym.

For all the activity reinvigorating the city, the Hammer is still a long way from L’Hammeur. Compared to Toronto’s relentless modernity, large swaths of Hamilton remain frozen in time: its streets are dotted with derelict strip malls, concrete buildings, businesses that operate out of houses and video stores that have somehow managed to survive in the streaming age. Many parking meters downtown charge just a dollar an hour and are free on weekends. We’ve found out the hard way that some businesses still adhere to pre-1990 operating hours—like when we promised Ellis a Sunday-night grilled cheese at his favourite Locke Street joint, the Burnt Tongue, only to discover it was closed for the day.

And yet for us, Hamilton’s balance of small-town pace and big-city amenities is just right. It’s a place where we can get a same-day reservation at a popular restaurant on a Friday night, and where there aren’t doormen with clickers counting capacity at every little bar. Where we can call our doctor to ask for the next available appointment and have the receptionist reply, “How does your afternoon look?” Where a 10-minute bike ride out of the downtown core can lead us to Cootes Paradise nature reserve in one direction or to the foot of a mountain in another. Hamilton, that great, smoky eyesore, feels like home.

As more people like me move to Hamilton, some locals worry that the city has become a glorified bedroom community for Toronto. But according to the 2011 National Household Survey, less than four per cent of Hamilton commuters—roughly 7,000 workers—were heading to Toronto for work, and 70 per cent worked within Hamilton proper. By contrast, some 40,000 people were coming into Hamilton for work on a daily basis. “I know a lot of people who moved here and commuted for a year or so. Then they got jobs in town, or worked freelance,” says Ryan McGreal, an urban blogger for the website Raise the Hammer. “They brought their home to Hamilton, but then they brought the rest of their life to Hamilton as well.”

That influx has led to a surge in housing prices. Hamilton is still cheap by Toronto standards, but the market is heating up. The average price of a home crossed the half-million mark this year; all told, it’s risen 47 per cent since 2012. Last October, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation red-flagged Hamilton as a market in danger of overvaluation, placing it in the same league as Toronto and Vancouver. Offer nights and bidding wars are now regular occurrences. One house on the Hamilton Mountain was shown more than 200 times and sold at $100,000 over asking. Another home, a detached Victorian, sold for $200,000 over asking after a fierce bidding war.

As builders encroach on Hamilton’s old neighbourhoods, a simmering resentment is building toward the upstart businesses that make rundown areas attractive to developers in the first place. Dave Kuruc, who owns Mixed Media, says that last year, the front door of his and neighbouring shops got slapped with a sticker that read “FUCK YOUR BOUTIQUE. DEFEND HAMILTON.” Last June, a bus tour for developers—branded “Try Hamilton!”—was interrupted by masked activists spraying sour milk out of water pistols and wielding signs that read “Developers + Investors = Predators.”

Toronto expats have been on the receiving end of online warfare. Matt Cowan, a tattooed chef who previously worked the kitchens at King West’s Portland Variety and Simple Bistro on Mount Pleasant, settled in Hamilton last year with his wife, Meg, to open a tiny 12-seat bistro called the Heather. It’s located on Barton, a downtrodden street on the northern edge of the James Street strip. “I was a blue-collar kid,” says Cowan, “so I gravitated to a rougher neighbourhood. I just fell in love with this street.” When word got out that Cowan’s restaurant would organize its dinner service around a $75 tasting menu filled with duck, snails and scallops, the reviews section on the Heather’s Facebook page was bombarded with negative comments decrying its incursion into a low-income neighbourhood. “This one guy was going off about how we’re taking money from Hamilton back to Toronto,” Cowan says. “We live above the restaurant!” After Cowan shut down the Facebook reviews, the action moved to the restaurant’s Google Reviews page. In May, the Heather’s front window was smashed by an angry local.

The Hamilton boom has created its own affordability crisis. Storefront rents have risen by 150 per cent in the past 10 years, and many sites are being earmarked for development. In the past decade, 2,000 rental units have been converted into condos, and the average one-bedroom rental cost grew by 5.1 per cent to $890 per month. The city’s economic rise and jacked-up housing prices have forced frustrated Hamiltonians to leave and seek out more affordable homes in nearby Brantford and St. Catharines. I spoke to Lee Reed, a hip-hop artist and activist who has lived in the core since the early ’90s, back when you could score shared accommodations for $150 a month. “Don’t get me wrong: Hamilton is an awesome, vibrant place to live now,” he says. “It’s just that fewer people I know, including myself, can afford to enjoy that. I can’t imagine what it’s like for a single mom with two kids who’s trying to keep her family in the same school and neighbourhood.”

Since moving to Hamilton, I’ve been amazed by the random acts of kindness I encounter on a daily basis: the strangers who routinely say hi on the street, the people who stop to hold a door open for you even if you’re 20 paces away, the multilingual “Hamilton Is for Everyone” signs in local restaurants that were designed to welcome the city’s recent influx of Syrian refugees. I’m also keenly aware that many Hamiltonians loathe the idea that the city is a blank slate that incoming Torontonians can refashion in their own image. Their city was once beaten up and left for dead—and the people who kept it alive are understandably wary of the newcomers who want to cash in. During one of Cowan’s first restaurant outings in the city, he struck up a friendly conversation with a fellow diner. Upon learning Cowan was from Toronto, the diner’s demeanour turned a few degrees colder: “Oh, so it’s your fault our real estate is going up,” he replied.

Back in Toronto, Ellis used to look out his bedroom window at the CN Tower. Waving good night to it was part of our bedtime ritual. In Hamilton, he immediately mourned its absence, repeatedly asking, sometimes to the point of tears, “Where’s the tower?” Since then, he’s become completely CN-obsessed: he’ll endlessly watch videos of tourists riding the elevators on YouTube, build his own replicas out of Lego and beg me to drive past it—if not go inside—whenever we’re in Toronto. I’ve been to the CN Tower more times in the past year than in my entire life in Toronto.

Depending on the time of day—and how heavy you step on the gas pedal—the drive from Hamilton to downtown Toronto can take 35 minutes or two hours. That seems fitting for two cities that are at once worlds apart and ever more intertwined. As the aftershocks of Toronto’s real estate boom continue to ripple outward, people who earn their salaries in one city are paying their taxes in the other. A fleet of sparkly new double-decker GO buses are shuttling people back and forth every day. The modern megalopolis and the old-fashioned midsize municipality are bending and blurring into each other. For my family, Hamilton was our endgame: a place where we could achieve a stability that we could never quite attain in Toronto. But Ellis’s tower-clinging experience speaks to a reality that many expats face. You can’t just quit Toronto cold turkey; you have to wean yourself off.

The Departed

Four more families who left Toronto to set down stakes in Hamilton

Leon Taheny and Christie Yao

Who they are: He’s a 33-year-old record producer; she’s a 34-year-old postdoctoral fellow in neuropsychology at St. Joseph’s Healthcare.

What they left: A $1,250-per-month loft in Parkdale.

When and why: In 2015 when Yao got a job in Hamilton. “I tried to commute from Toronto to Hamilton, but it was too much for me.”

Where they moved: This three-bedroom detached house near the trendy shops and cafés on Hamilton’s Locke Street.

What they paid: $370,000.

Kelci Archibald and Matias Rozenberg

Who they are: She’s a 38-year-old career counsellor; he’s a 47-year-old shiatsu and Registered Massage Therapist; they’re shown here with their two-month-old son, Felix; and their rescue dog, Ralfie.

What they left: A $1,250-per-month two-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a house in Parkdale. “We only ever had our single friends over because we didn’t have enough room around the table for four,” Rozenberg says. “If I needed something from the fridge, everybody had to stand up so we could open the door.”

When: In 2013.

Where they moved: This four-bedroom detached house in downtown Hamilton, with a separate basement unit that Rozenberg transformed into a massage clinic.

What they paid: $190,000.

Ian and Tarja Thresher

Who they are: He’s a 41-year-old sommelier; she’s a 39-year-old interior stylist; they’re shown here with their daughters, five-year-old Neve and eight-year-old Sloane.

What they left: A three-bedroom townhouse in Oakville. After three years, they got bored with suburban life. They couldn’t afford a place in Toronto, so they started looking in Hamilton.

When: In 2014.

Where they moved: This four-bedroom Victorian house in Hamilton’s Strathcona neighbourhood. “It reminded me of the High Park house where I grew up,” Ian says. The place was listed at $350,000. After a 10-way bidding war, they got it for $26,500 over asking.

What they paid: $376,500.

Lindsay Forsey and Doug Blendell

Who they are: She’s a 38-year-old entrepreneur; he’s a 41-year-old sales manager; they’re shown here with their kids, five-year-old Edie and two-year-old Leni Mae.

What they left: A $1,650-per-month three-bedroom apartment in Dovercourt Village, with on-site laundry and a small backyard.

When and why: In 2015 when their landlord took over the unit.

Where they moved: This four-bedroom century home in Delta, an affordable east-end Hamilton neighbourhood filled with many Toronto expats.

What they paid: $282,500.

Correction

An earlier version of this story identified the wrong Burnt Tongue location.