The Only Woman in the Room

Irene Cybulsky was a superstar surgeon—the only woman in Canada to head a cardiac surgery division—but her all-male staff resented her. When she was replaced with a man, she found a novel way to seek justice

The lessons about a woman’s supposed place in the world started early. Growing up in Toronto near High Park, Irene Cybulsky watched as her two older brothers were accepted to the boys-only University of Toronto Schools. As she was just about enter Grade 8, the school announced it would allow girls. Irene, a clever, confident kid, aced the entrance exam and joined the inaugural co-ed class, each female student receiving a single red rose upon arrival. The school wasn’t quite prepared for the change: there were no washrooms for girls, so they had to use the old faculty of education ladies’ locker room. Those girls, bonded by their shared status as outsiders, coalesced into young feminists. Cybulsky still owns a button that reads WHY N♀T in white letters.

In her second year of undergrad at the University of Toronto, she applied to its medical school, one of 2,043 students vying for 252 spots. Her grades were impressive enough to get her on the wait-list, where she remained all summer until, at least as she heard it, a student fainted while looking at a cadaver. She was in.

This was 1984, and medicine was still very much a man’s world. Approximately two out of every three graduating doctors across the country were men—the most prestigious postings were largely occupied by males, too—although U of T was in some regards among the more progressive institutions. Forty per cent of Cybulsky’s classmates were women.

Cybulsky was a pragmatic person who liked to solve problems, and as medical school came to an end, she was drawn to surgery as a specialty. A clogged aorta. A ruptured appendix. A tumour. You found a problem and fixed it.

She completed a year-long surgical internship then applied to a general surgery program, but the acceptance letter never came. Cybulsky believed she was among the stronger candidates. She had more surgical experience and knowledge than at least one of her male classmates who been offered a similar slot. It was impossible to say definitively that her gender had played a role, but she couldn’t shake the idea that it might have. It would have been easy to forget about surgery and choose a different, more welcoming specialty. But that wasn’t her way. She spent a year completing a master’s in research science, then applied to general surgery at McMaster University in Hamilton and got in.

Women got less hands-on training than their male colleagues, and their skills might develop slower, fuelling the pervading criticism that they weren’t cut out to be surgeons

By this time, the number of women in medicine in general was higher than ever, but surgery was still male-dominated. At McMaster, there were no change rooms or even showers for the female surgeons. Staff surgeons, nearly all of whom were men, controlled how much hands-on time a trainee got in the operating room. Though Cybulsky didn’t experience this directly, she witnessed attending surgeons limit women’s participation in operations, leaving trainees to stand and watch—a pattern that is still borne out in studies of surgical residents today. It was something of a vicious circle: women would receive less hands-on training than their male colleagues, and their skills might develop slower, fuelling the pervading criticism that women weren’t cut out to be surgeons.

Given that backdrop, it’s not surprising that by 1990, women accounted for less than seven per cent of all surgeons registered with the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada or its equivalent in Quebec. And of the women in surgery, an estimated 40 per cent worked in obstetrics and gynecology, according to a 1993 report in the Annals of Surgery.

Yet Cybulsky decided to further specialize, in thoracic surgery. The first place she applied, in Toronto, turned her down. Cybulsky had heard the whispers: the program had had a female resident once before, but her technical skills were lacking, and the hiring committee wasn’t interested in repeating the experience.

Cybulsky applied successfully to McMaster in cardiovascular and thoracic surgery, a specialty in which only 2.7 per cent of surgeons were women. You could almost count them on two hands. She trained for two years before signing a one-year contract as a cardiac surgeon in Toronto. Her boss told her that if she impressed, she might be hired permanently. But at year’s end, the hospital hired a man instead. Her boss gave her a reference letter emphasizing that she took good care of patients and got along well with nurses, but he sidestepped what mattered most to hiring committees: Cybulsky’s technical abilities as a surgeon. The letter burned at her. “[My patients] do well because I did a damn good operation,” she told the author Judith Finlayson for a book about women in the workforce, “but that gets lost.” Cybulsky considered suing the hospital, but finding employment as a female surgeon was already challenging enough, and she decided that a lawsuit could tarnish her reputation. “If they don’t want me,” she said, “it’s not a wholesome situation.” And so Cybulsky chose a path well travelled by decades of smart, successful, ambitious women who had come before her: she suppressed her feelings and carried on. It would be a test run for the bigger battle that lay ahead.

By 1995, at the age of 34, Cybulsky finally found a home, at Hamilton General Hospital, which would later become part of Hamilton Health Sciences, a network of hospitals affiliated with McMaster University. She worked first as a clinical assistant and fellow, then came on staff as a cardiac surgeon and program director for cardiac surgery residency at McMaster. She often biked to the hospital early in the morning and left for home after dark. Her husband, an officer with the Ontario Provincial Police, would jokingly refer to her as “the late Dr. Cybulsky.”

As a communicator, she was direct. If something could be done better, she said so. Stephanie Brister, a cardiac surgeon who overlapped with Cybulsky during her first years in Hamilton, says Cybulsky’s combination of surgical skill and total commitment to what was best for patients made her an excellent physician. But her high expectations could be difficult for colleagues. “She would take that commitment to surgical skill and patient care and set a pretty high standard,” says Brister.

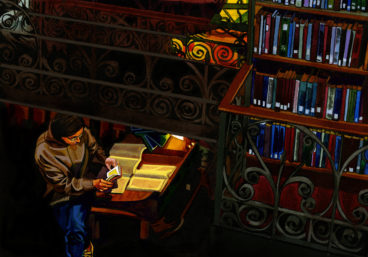

Once Brister left, all the surgeons and residents in Cybulsky’s division were men; so too were most of the ICU physicians, anesthesiologists and cardiologists with whom she interacted. In a photo published in the department of surgery’s annual report, Cybulsky stands among her male colleagues and grins; her short, wavy hair is pushed to the side, a pager fastened to the belt of her skirt.

For a time, there was another female specialist in the division, Ama deGraft-Johnson, a cardiac anesthesiologist who was born and trained in Ghana and came to Hamilton General in 1982. At work, racism abounded, from patients and colleagues. So did sexism. Sometimes, when deGraft-Johnson and Cybulsky were shadowed by young male residents, their patients would look past them and speak to the men. DeGraft-Johnson would interject to explain that she was the one who was qualified to take care of them, and that on the surgical table, their lives were in her hands. She focused on not letting the discrimination get to her. “I could have been depressed. I could have been suicidal. For what? For being a female doing my job?” she said.

She and Cybulsky called each other “my sister,” and they learned to pick their battles—and there were many to choose from. When patients or colleagues would make note of deGraft-Johnson’s skin colour or accent, she would tell them she’d been educated in a jungle school. The male surgeons and surgical assistants would go on a yearly ski trip; Cybulsky, who was a skier, was never invited. At a party, some of the hospital staff had watched a porn featuring a character named Irene. At work, they would say to Cybulsky, who wasn’t at the party, “Goodnight, Irene. I’ll see you in my dreams.” Cybulsky’s response: “I’ll be in your nightmares.” Some comments, in her estimation, went too far. When she heard a surgeon refer to a surgical suction device as “the Monica”—as in Lewinsky—Cybulsky called him out. The times had changed, she said, and so had expectations.

In 1998, Cybulsky became pregnant. She kept operating around her growing belly. If she had to take time off, she wanted to do it after the baby arrived. She didn’t want to ask colleagues to cover for her any longer than they had to. But women surgeons have higher rates of pregnancy complications, especially if they’re operating through their final trimester. And at 29 weeks, Cybulsky developed a deep vein thrombosis and was admitted to her hospital. To her frustration, the university administration refused to cover her sick leave and instead wanted her to start her maternity leave early. “Getting sick while pregnant is still getting sick,” she told me. She eventually convinced them, but the experience taught her a lesson: organizations need policies to protect employees from discrimination. If left to goodwill, nothing will change.

In 2009, Cybulsky was promoted to head of cardiac surgery at Hamilton Health Sciences and division head at McMaster. It was a five-year appointment, renewable once. The salary was negligible—a bump of just $5,000 a year—but the significance was huge. She was the first woman in Canadian history to head a cardiac surgery division.

The job was complicated. The division handled more than 1,700 cardiac surgeries a year, making it one of the busiest centres in the country. It was under constant strain, perpetually short on beds, staff and operating rooms, and facing the ongoing threat of funding freezes from the provincial government. There were internal battles to manage, too. Surgeons jostled for operating room time and would bump their own patients up on the priority list when they could. The surgeons, all of them competitive, didn’t always get along with each other.

Leadership meant dealing with adversity. Cybulsky knew that it wasn’t her job to be liked; it was her job to provide the best quality of care to patients

Cybulsky’s first objective was to get the team to co-operate. Based on the recommendation of a third-party review, she set out to reform the way patients were referred for cardiac surgery. The existing system was based on relationships: cardiologists often sent their patients to surgeons they knew. As a result, some surgeons had wait-lists several months long, while others found themselves scrambling to find patients to fill their assigned OR days. Cybulsky’s own wait-list was on the shorter side. The arrangement led to some patients languishing on the wait-list while others leapfrogged to the front of the queue. And the problem was self-reinforcing: a surgeon with a long wait-list accrued the prestige of being in demand and received even more referrals.

To Cybulsky, the system contributed to the fractious environment within the division. She also saw it as an example of the insidious way gender dynamics infiltrated her profession. Studies suggest that she had a point. A 2021 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that male physicians in Ontario disproportionately refer to male surgeons. Another study suggested that women surgeons are less likely to receive referrals after an unexpectedly bad outcome, while the same is not true for men. When a female surgeon has a complication with a patient, the referring doctor is less likely to refer patients to any female surgeon. Women typically receive more referrals for non-operative patients and perform fewer highly remunerated surgeries. As a result, on average, women surgeons in Ontario earn less than men for the same hours worked.

Cybulsky set out to transform the system. Patients awaiting surgery would go on a centralized list, and whichever surgeon was on call would perform the operation. That way, all the surgeons would perform roughly the same number of surgeries per year and all patients would have similar wait times.

Internally, the change was wildly unpopular. Some surgeons were furious that their income would be reduced; some were outraged that their patients would potentially be operated on by less-proficient surgeons. Some cardiologists tried to invent a workaround—they’d wait until their preferred surgeon was on call to refer their patient.

Yet the change was logical, fair and consistent with how things worked in other surgical departments. Still, the surgeons who were most opposed couldn’t get past it. So they focused their rage on the person who’d made the change. Word of their displeasure inevitably reached Cybulsky, and she knew she’d come close to mutiny in her division. But she also knew leadership meant dealing with adversity. It wasn’t her job to be liked; it was her job to lead and to provide the best quality of care to patients. Important change didn’t happen without fallout. And there was more to come.

In September 2013, Cybulsky moved on to her next objective. She assembled a selection committee to hire two new cardiac surgeons, bringing the total to eight, a target set out in the division’s strategic long-term plan. The new hires would help shorten wait-lists and boost research productivity. Most surgeons would still perform around 200 open-heart surgeries a year. Some surgeons supported the idea, believing that more hands were needed. Others worried that more surgeons meant less income for them. If a hire was going to be made, several surgeons wanted it to be the popular surgeon who had done fill-in work with them. The hiring panel, which Cybulsky sat on, considered him but found he was prone to throwing temper tantrums with nurses—Cybulsky and an ICU physician had addressed the issue with him. In the end, the committee hired two other surgeons instead.

When word of the decision got out, the already aggrieved surgeons saw the decision as another example of Cybulsky’s authoritarian manner. A division-wide meeting where the surgeons officially agreed to the new hires did nothing to quell the unrest. They saved their fiercest criticism for moments when Cybulsky wasn’t around. They met one night at a restaurant in Hamilton and discussed what to do about her.

Soon after, at least two surgeons approached Cybulsky’s boss, the interim head of surgery, Kesava Reddy. One of the surgeons, a young rising star in the department with an impressive research resumé, threatened to quit if Cybulsky wasn’t ousted. Reddy worried he’d be blamed if that happened.

In Reddy’s four years as a surgical leader, he hadn’t experienced any problems with Cybulsky. She had her detractors, but so did many leaders who made tough decisions. She was hard-working and experienced and possessed all the characteristics the surgical profession is famous for: assertiveness, confidence and meticulous attention to detail. She had good working relationships with nurses and other physicians. She could deal with strong personalities and also collaborate. But he had to listen to the naysayers, too. Her detractors felt she was a dictator, and they wanted her out.

This was a problem for Reddy. Beyond some grumbling, there was nothing actionable to warrant a standalone review of her leadership. But if he did nothing, a star surgeon might walk. So he launched a review of the entire cardiac surgery division that would examine her leadership as well. It would give disgruntled surgeons an opportunity to voice their displeasure without requiring that Cybulsky be fired.

Cybulsky returned to work after Ukrainian Christmas in January of 2014 to this surprising news from Reddy. A pediatric surgeon named Helene Flageole would lead the review. This was unusual. There had been departmental reviews, but never a leadership review. Cybulsky asked some basic questions—why? who?—but Reddy cut her off. Cybulsky said she didn’t even know what the allegations were or who’d complained about her. How could she defend herself? Reddy wouldn’t elaborate.

Cybulsky surreptitiously activated the recorder on her phone. If she was going to be fired, at least she would have proof as to why

Cybulsky was left to piece together the puzzle herself. While she didn’t know what, specifically, had triggered the review, the broad contours were obvious to her. There had been many unpopular male heads of service, but they had never undergone a leadership review. She had risen through a system that was biased against women. She’d pushed for change. The system, it seemed, was now pushing back. If her fears came true, she could be forced out of her position. And as for the reasons why, it would be her word against theirs.

Or maybe not. If she surreptitiously recorded the conversations that lay ahead, she would at least have proof as to why.

On February 7 in 2014, Cybulsky activated the recorder on her phone before she sat down to a meeting with Reddy. She began by explaining how confused she was: “I look at the facts, I see intrigue, I see a conspiracy and then I wonder if this is all in my head,” she said. Reddy admitted that he’d had no issues with her and that he had only positive things to say about her. He hoped the review would be mostly about the department itself. As for Cybulsky’s leadership, he expected that Flageole would conclude Cybulsky was doing a good job, but that she needed to be, in his words, “a bit fluffier.” He added, “I think you’re not really a fluffy, hand-holding type person, like I’m not.” It was a perplexing statement. She wasn’t fluffy, nor was he, and yet… she should be? Why? And for whose benefit? She tried to interject. He kept talking. She tried again. He dodged.

Cybulsky tried to carry on with her duties, but it was hard to shake the fact that her colleagues had gone behind her back to trigger a review. At times, tensions flared into open hostility. When a surgeon covered a colleague’s overnight surgery shift even though he’d just operated through most of the previous night, Cybulsky confronted him. She said he was too tired to operate; he disagreed. She sent a surgical assistant home and scrubbed in to assist. She reported the incident to Reddy and said it was a recurring pattern and that the surgeon did not respect her position of authority.

Flageole met with several of the cardiac surgeons and other health care workers in the division. One of the cardiac surgeons was supportive of Cybulsky’s leadership. He said her heart was in the right place, she was trying to bring the group together, and she was respectful, considerate, firm but appropriate. The rest were hostile. Cybulsky was, several said, a bully. She went behind surgeons’ backs to read their patient charts (which was in fact commonly done and medically necessary). One said she acted like “a mother telling her children what to do.” Another said she forced surgeons to take on cases they were uncomfortable with. They said Cybulsky had destroyed the collegiality within the group. They said they were afraid of her. It was damning stuff. A female cardiac anesthetist had something different to say: she felt there was a broader context to the unrest—specifically, gender. Flageole’s handwritten notes for the meeting read: “no respect by group—female.”

Flageole revealed none of those complaints in her meeting with Cybulsky. Instead, she asked the surgeon about her communication style. “I think I can be quite direct. I can be assertive,” Cybulsky replied. Then Cybulsky raised the issue of gender. She thought her male colleagues struggled to accept her leadership because she is a woman. She referenced literature that described the central tension she faced every day. Leadership was traditionally thought of as a male domain and exemplified by so-called male attributes, like assertiveness and directness. Women, by contrast, were expected to be nurturing and fuzzy. And here she was, a naturally direct and assertive woman. Her subordinates simply could not bear the combination. “It is a male world where accepting a woman as a leader is just psychologically difficult,” Cybulsky said to Flageole. “I’m probably as guilty of it myself toward other women leaders.” Her gender, in other words, was central to the insurrection, not incidental. These were important, explosive claims. But Flageole disregarded Cybulsky’s comments and moved on.

Flageole later told her boss, Richard McLean, who was then the executive vice-president and chief medical executive at the hospital, that some of the conflict was due to “boy-girl stuff” (something she would later deny saying). She gave the review to Cybulsky. Three days later, during an in-person meeting with Reddy and McLean, Cybulsky, who was surreptitiously recording the meeting, pointed out that the review said nothing about being a woman in a leadership position. McLean levelled with her. She was right, but they weren’t about to state it publicly. “It is not in writing in the report, but Helene [Dr. Flageole] would acknowledge that some of this may well be because you are a woman and they’re men,” he said.

Ultimately, Flageole, McLean and Reddy recommended that Cybulsky receive coaching and training on her communication style. That summer, her appointment as leader was renewed on schedule. In the fall, Reddy was replaced with an Australian doctor named Michael Stacey. Cybulsky told him of her concerns about the review. Stacey said he was still acclimatizing to the new job, but he’d like to meet with her regularly to help improve the workings of her division.

Over the course of the following year, however, despite occasional divisional meetings led by McLean, Cybulsky received none of the promised support—no coaching, mentorship or regular one-on-one check-ins. Stacey conducted no formal assessment of her performance. He had, however, read Flageole’s review, which including the surgeons’ scathing assessments of Cybulsky. He also met members of the cardiac surgery team and in some cases discussed their opinions of her.

Then, in September of 2015, Stacey delivered devastating news. He was opening her position to new applicants, and he encouraged her to resign. Cybulsky refused to comply. Why would she? She was working hard and, she thought, effectively. She fired back by filing a written complaint about Stacey to McLean.

Cybulsky met with a series of administrators, who described her as “very aggressive in her dialogue” and focused on “process.” But clarity on process was exactly what she sought. If she was being dismissed from her position, shouldn’t she know why? Shouldn’t she have had a chance to address any shortcomings? Shouldn’t she be supported in that effort? And why hadn’t the hospital taken her claims about gender discrimination seriously?

Her relationship with her surgical colleagues, already under strain, got worse. On a Saturday morning in December, Cybulsky learned that one surgeon had bumped his own patient ahead of hers on the weekend priority list without telling her. She walked into the operating room and confronted the man, who became so flustered at her presence that he had to step back from the table. “I’m upset right now. And I can’t sew,” he told her. The anesthetist told them cool it—there was a patient in front of them who needed care.

Cybulsky put her concerns in a letter to the human resources lead, Jane Hastie. “I have read about challenges in leadership for women and I believe the bias against female leaders is accurate and has played a role for what has been happening in my case,” she wrote. Hastie, like Flageole before her, sidestepped the claim. The hospital did nothing to investigate.

She could have gone away quietly, but she had a better idea: to go to law school and represent herself in a human rights tribunal case against her former hospital

In July of 2016, Stacey dismissed Cybulsky as head of cardiac surgery, seven years into what was supposed to be a decade-long tenure. Cybulsky remained a cardiac surgeon with privileges at the hospital and head of cardiac surgery at McMaster University. She still had a glittering reputation for patient care. She could have continued on and bade good riddance to the position that covered barely two per cent of her clinical earnings and created most of the stress. But Cybulsky had other ideas: she was already deep into planning her second act.

A surgeon’s hours are long. The work takes a toll on backs, necks and hands. Cybulsky had spent three decades in operating rooms. She’d attended retirement parties of nurses and other colleagues who’d started their careers when she was a resident. For years, she’d been thinking about a life after surgery. An energetic, restless person, she’d found the time to complete a master of public administration at Queen’s University in 2010, and afterwards contemplated a career in law. She felt she couldn’t leave surgery just as she was establishing herself as head of service. Her role was bigger than just her. “Women had to show that they were in for the duration,” she told me, “not just the short or mid-term.” Yet the allure of law, with its intellectual challenge and analytical thinking, stayed with her. And so in the weeks after her dismissal as head, she threw herself into preparation, and her efforts paid off. With her LSAT score and her professional background, she was a strong candidate. Her first acceptance letter—from the University of Windsor—arrived before Christmas, and several others followed.

It was a welcome new challenge. Still, the dismissal weighed heavily on Cybulsky. She was distressed and sleeping poorly. She worried that what happened to her would happen to other female surgeons. Her husband, who had retired from the OPP, was familiar with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. He had encouraged an acquaintance to pursue justice there in the past, and he strongly encouraged his wife to do the same. Cybulsky was unsure. She guarded her personal life carefully and worried about her privacy. (For this piece, she agreed to answer my questions by email only.) That summer, she made up her mind and filed a complaint at the HRTO against Hamilton Health Sciences and five of its leaders. In it, she argued that she was dismissed as head not because she was an ineffective leader but because she was a woman trying to lead a group of men in a place where a woman leader wasn’t wanted. “When there is only one female cardiac surgeon among the eight surgeons and she is the leader, gender dynamics is a factor that cannot be ignored,” she wrote in her application. She referenced the gendered language used in criticisms of her. She said that Flageole’s review suggested that a female leader should be deferential and wait on those she is to lead, rather than give direction to them. The glass ceiling, she argued, was still very much intact.

Cybulsky closed her surgical practice, and she and her husband moved to Kingston so she could start law school, at Queen’s. She was in her mid-50s. In June of 2017, her hearing began in Hamilton. The hospital brought in a team of expensive lawyers—eventually spending more than $850,000 on the action; Cybulsky represented herself. Her husband sat nearby and took notes, which he’d hand to her at the end of the day.

Human Rights Tribunal hearings look very different from a court cases: they take place in conference rooms in hotels or convention centres, and go on for a few days here and there. There’s no stenographer and therefore no transcript. The hearings are the last line of defence against discrimination and harassment, and the policy is to resolve cases in a “fair, just and timely way.” Yet under Doug Ford’s government, the number of full-time adjudicators dropped from 22 to 11, and hearings sometimes last years. The glacial timeline would be laughable if the stakes weren’t so high.

The original adjudicator in Cybulsky’s case announced his departure after a few days of hearings, which meant they had to start over. The delay was bad news for HHS’s lawyers. With each passing day, Cybulsky sat in class at law school and soaked up knowledge. Sometimes, she’d have to miss class for the hearing, so she’d read ahead in her courses. Other times, she’d schedule hearings during academic breaks. Soon, she and her husband had established a rhythm: they’d drive to Hamilton the night before the hearing and settle into a hotel, opting for places with kitchenettes so she could prepare in comfort. They had a running joke about what would finish first: the HRTO claim or law school.

In Cybulsky’s first year of law school, none of her classmates knew that she’d been one of the most accomplished cardiac surgeons in the country. In surgical training, she’d stood out as a woman; now, she was unmissable as one of the oldest students in the class. Classmates noticed that she was extraordinarily energetic. One remembers Cybulsky running along the pathways of Kingston before class many mornings. When the subject of medical malpractice came up in class, she joined the discussion with a detailed knowledge of medicine and medical ethics that surprised even her professors.

As she studied, Cybulsky collected information and tactics she could use in her claim. She read about a human rights case where the applicant raised the issue of men-only ski trips, and she flashed back to the ski trips that only the males at HHS were invited to. In Cybulsky’s second year of law, a professor covered a case about an employer’s duty to investigate discrimination complaints. She recalled her meetings with the hospital’s human rights and diversity specialist, where her discrimination claims were disregarded. She learned the nuts and bolts of witness examinations, then drew on those lessons as she cross-examined her former colleagues.

Three years after Cybulsky filed her complaint, the hearing neared its end. She organized her own course with a dedicated instructor in order to review case law on gender discrimination in leadership. She used the cases from that course and her husband’s notes from the hearing to craft her closing arguments. “I believe that I have established a prima facie case of gender-based discrimination and harassment,” she said. She pointed out that gender-based discrimination did not have be the sole cause of her mistreatment or even the reason she was removed as head of service; it just needed to be a factor. She zeroed in on the review led by Flageole, Reddy and McLean. “They relied on subjective input of male cardiac surgeons, who have never been led by a female, and who were working in an environment where their senior physician leaders are and have always been male,” she argued.

HHS countered that the review had not been gendered and that Cybulsky’s complaints were not about specific instances of gender discrimination; instead, she was speaking in general about existing literature on the subject. They argued that her claims were speculative and subjective.

In March of 2021, the tribunal found that Cybulsky’s rights were breached three times: when Flageole and McLean ignored her comments about gender, when the HR specialist did the same, and when Stacey opened her job up to new applicants.

“It is an act of discrimination to fail to take seriously the applicant’s allegations about the relationship between gender and perceptions about her leadership,” the adjudicator, Laurie Letheren, the vice-chair of the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, wrote. “Her dignity and self-worth were undermined, and those consequences are directly connected to the fact that the applicant is a woman.”

The decision also faulted the hospital for not embracing Cybulsky’s gender. “One might have expected that having the only female head of cardiac surgery in Canada would be something that a teaching hospital such as HHS would want to celebrate,” Letheren continued. “Unfortunately, this was not the applicant’s experience. The role that her gender played in her experience in the context of this male-dominated profession was ignored.”

For Cybulsky, the claim was never about money. She asked for just $49,500 in financial compensation—$19,500 for lost income and $30,000 in punitive damages. What she was really after was the creation of written policies at HHS that would help prevent gender discrimination, and for required reading for staff on the role of gender in the workplace. She doesn’t want her experience to dissuade other women from pursuing leadership roles in medicine, or from going into medicine altogether. The HRTO has yet to announce remedies.

Representatives at HHS declined my interview requests but, in a statement, listed initiatives the organization had taken to foster equal opportunity at their sites. Among them were hiring specialists in equity and discrimination, establishing policies for leadership appointments and providing leader training on implicit biases. They said the organization will “act swiftly” to address any issues identified by the HRTO once its decision on remedies are finalized.

Stephanie Brister, Cybulsky’s former colleague, said she views the tribunal’s decision as a watershed for women surgeons. “I hope there’s a real soul-searching, and a commitment to bringing in policies, and enforcing policies, that lead to more equitable treatment of women,” she said.

Cybulsky graduated with her law degree in June of 2020, finally answering the question she and her husband used to laugh about—what takes longer: a human rights tribunal claim over gender discrimination, or law school? The answer is the former, by about nine months.

Cybulsky now lives in Ottawa where she is midway through a one-year clerkship at the Federal Court. When I asked her about her plans in law, she declined to answer, as guarded about her privacy as ever. “I didn’t seek stardom as a fighter against discrimination,” she told me. She believes it’s still very hard for women to speak out in the face of discrimination. The cost of doing so is too great. “HHS knows there won’t be many cases against them at the HRTO,” she wrote. “[That’s] because most women come to realize that it’s not the hill they are going to die on. I considered the cost in time, the impact on family, the stage of my career…I persevered as the HRTO process progressed, and I realized this was my hill.”

This story appears in the January 2022 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $29.95 a year, click here.