The Homesteaders of Mount Forest

Bryce and Misty Murph’Ariens live off-grid with two kids, 41 animals and no regular income. Life was a fairy tale until they became locked in a legal battle with the township. Now, they could lose it all

After spending several weekends at a cabin north of Toronto, Misty Murphy and Bryce Ariens—two frazzled city-based chefs—decided they wanted out of the grind permanently. They got married in the woods, portmanteaued their surnames and became homesteaders. That’s the practice of living off-grid, an alternative lifestyle that bears many attractive qualities in the age of the pandemic. The Murph’Ariens wanted to leave behind not just city life but money—earning it, spending it, relying on it—too. They built a beautiful home out of clay, sand and straw. They farmed, raised livestock and developed ways to live peacefully off the land. They had two daughters and schooled them in their way of life. The Murph’Ariens thought they’d made their dreams a reality. And then the building inspector came knocking. Here, the story, in their own words, of how it all happened.

Misty Murph’Ariens: My mom, who had ALS, died in 2004, the year before Bryce and I got together. It was hard for me, but it really cemented how short life is and that you need to do what you want to be doing. My brother and I inherited the family house. And, while I loved it, I didn’t super love exactly where we were living—it wasn’t a very knitted community.

I was studying at McMaster to become a forensic anthropologist at the time, and I just felt the way people feel about the rat race. So I left and started working as a chef for this little Polish restaurant called Rumak Eatery and Bar. Bryce was working as a chef at Shakespeare’s Steak and Seafood, like the fanciest restaurant in Hamilton. I realized that, if I succeeded at my career and Bryce succeeded at his, we’d never see each other. And I was like, “I found true love—I’m not going to just see you on the weekend.”

Bryce Murph’Ariens: I was living in an apartment in Hamilton with one of my best friends from high school. I didn’t know then that there was something more fitting for me. I was doing what was expected of me, pursuing a career. But, at the same time, I was really stressed out and didn’t have a lot of personal time.

One weekend, I took Misty to my grandparents’ cabin near Priceville, 15 kilometres north of where we live now. Just nature, nature, nature, nature—it was a wonderful place to be able to get away from the city. I have extremely sensitive hearing, and every fluorescent light fixture puts out this exceptionally high-pitched buzz, but I didn’t hear it when we were out of the city. And Misty had migraines basically all the time except when we were at the cabin.

Misty: Every weekend it was like, “Can we go back to the cabin?” We went 54 weekends in a row, and that’s when I convinced Bryce that it would be a lot more affordable if we weren’t driving back and forth. By 2006, we had both quit our jobs and I had sold my half of the family house to my brother for $100,000. We mostly lived off that money. We also got rid of our car because we didn’t want to pollute and bought a Rhoades pedal car online.

Bryce’s grandmother still owned the cabin but wasn’t big on visiting it. She said we could live there temporarily. I remember her saying, “You’re gonna hate it. You’ll be home in a month.” We foraged for food and collected our own water. We got books that taught us what’s edible in nature. It was hard adjusting to wintertime. There was no power and no running water. But we had both camped a lot as kids, so we had survival skills. We didn’t hate it.

Bryce: We never felt lonely. We had each other, and in the summer of 2008, we got married there. A week after the wedding, we got a real estate flyer in the mail that listed an interesting property in Mount Forest for sale.

Misty: We had $70,000 left of my inheritance after living at the cabin for nearly three years. The property on the flyer was a marshy nine-acre parcel of land with a dilapidated plywood bunkie, but it was miles better than having a matchbox in the city. It was listed in the $40,000s; we offered them $37,500 and they accepted. We took possession in August 2008.

Bryce: In our first four or five years, we supplemented nature’s abundance with occasional catering gigs, but we were always trying to figure out how to do this thing without money, an idea I probably got from my dad.

My mom and dad separated when I was four years old, and my mom was the one who mostly raised me. For much of his young adulthood, my dad was very free-spirited. His lesson for me was how to be a free person on this earth. He also taught me important lessons about personal sovereignty and responsibility. He liked the concept of a cashless society and at one point started a pay-what-you-want art gallery called the Gift, but that didn’t end up working out at all.

Misty: My family comes from a more serious and stoic tradition. It’s all about work and perseverance. My mom was from Hamilton and my dad was from Texas, and if you can think of a 10-foot-tall Texan who had been in the military, that was my dad’s personality and his job. As a dad, he wasn’t like, “You’re not strong enough. You can’t do this.” It was more like, “I don’t care if you’re a girl or a kid or whatever—you can do this. You’re gonna get up on that roof and help me fix it.” His approach to parenting brought me to a level of self-discipline that was a bit joy-denying.

Bryce: We have come to a simple philosophy about money that is really hard to describe to outsiders. There’s a classic line from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory where Grandpa George says, “There’s plenty of money out there. They print more every day. But this ticket—there’s only five of them in the whole world, and that’s all there’s ever going to be.” Money can come, money can go, but an authentic life filled with purpose and direct access to essential needs is so much more valuable.

Misty: I think money has people hypnotized. We’re trying to strike a middle way where there’s responsibility and duty but also a sense of making things for yourself and not having an addiction to money. But we didn’t come to that world view until later.

At the time we bought our property, in 2008, all we were thinking about was that we needed a house to live in and we had no money to buy anything. So, while staying at the cabin that winter, we researched what to build. We went down a rabbit hole that led us to the book The Hand-Sculpted House, which is like the bible of cob.

Bryce: Cob is a mixture of clay, sand, straw and water. It’s been used for almost a thousand years to make homes, and it was popular in the Tudor-style buildings of the 15th through 17th centuries. The recipe is between five and 15 per cent clay, 60 to 80 per cent sand, and the remainder is straw. Then you add water to make it malleable.

Misty: When it starts to form like mud, you know you’re done, and you can stack it onto itself like Lego. Cob stores temperature—you can make refrigerators and ovens out of it. In the winter, it keeps the house warm; in the summertime, it holds the cold of the overnight.

Before we started building, we called an official at Southgate Township, and I asked him about cob earthworks in general. He said if we didn’t use heavy machinery, we wouldn’t need a permit. Then I asked him if, hypothetically, an agricultural worker could live in a 10-by-10 structure like a bunkie, and he said we wouldn’t need a permit for a structure of that size. The tone of the conversation was like, “Lady, stop asking me questions.” Basically every answer was, “I don’t know, I guess?”

That spring, we stayed in a gazebo tent and stored our food in an old camper that a neighbour sold to us for $50. Then we started building a one-and-a-half-storey cob structure. We built the walls in the standard stick-frame method out of two-by-fours. Then we reinforced the walls with two-by-sixes cut on angles to replace the plywood and used cob, instead of insulation and sheetrock, for infill.

We got the wood for the main building from the dilapidated bunkie on the property. We disassembled it and made the design based on the pieces we could salvage. People started hearing that we were going to do this build and they were like, “Oh, hey, I’ve got some windows in my barn.”

Bryce: The only tools we had were two handsaws, two hammers and a box of nails. We did buy two pry bars so that we could pull all the old bent nails out of the broken-down building.

Misty: Bear in mind our only vehicle was the four-wheel pedal car, and town is like a three-hour ride away, so just a box of nails and crowbars meant a considerable back and forth. We certainly weren’t going to be bringing home, like, circular saws.

Bryce: Initially, we had our kitchen, living room and tool storage all on the main floor with the bed up top, but we’ve since reconfigured the layout.

In all, the 10-by-10 structure cost $450 to build. Most of that was for the extra wood planks for the floor of the second storey. We also spent $40 on a chandelier—that was a big deal from a thrift store—and $60 for a locking doorknob that we thought was important before we realized that we’d be home almost all the time. The wood stove was $110. With all the furnishings, the total came to about $660.

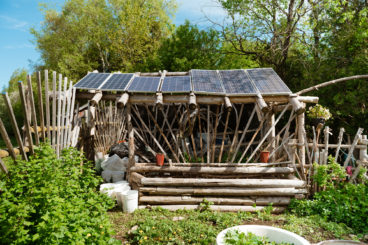

These days, we don’t need much electricity because the cob moderates the temperature, but we do have solar panels that generate about 600 watts, a 1,500-watt inverter we got at Canadian Tire and two batteries that allow us to run the fridge, freezer and lights and to charge our phones.

While we have a lot of things we got for free, we do have expenses: property tax, telephone and internet, firewood, plus we spend about $300 a month on animal feed.

Misty: We started with a couple of Norwegian Fjord horses, named Kodjisaam (pronounced cody-sam) and Hygge (pronounced hew-ga). We now have two cows, one bull, the two horses, 10 ducks, 21 chickens and five cats, who are not just five random cats: they’re a family.

We used to have pigs and eat meat but don’t eat much meat anymore. My feeling is, if you want to eat meat, you should kill an animal at least once and then eat it. I think anyone who does will eat a lot less meat. Our property is roughly nine acres, two of which we use for farming and the rest is mostly wetland, which is great for permaculture.

Bryce: Permaculture has 12 principles, but for us it just means trying to think and live in the most sustainable way possible where there is no such thing as waste—everything that comes from the land goes back to it.

Misty: We started with a veggie garden. Then we put in fruit trees. Not only does sea buckthorn make a beautiful fruit that tastes like a cross between an orange and a lemon, but the leaves are high in protein and they make a lovely tea. We have raspberries, garlic mustard greens, tomatoes, elderberry, black currant, turnips, radishes—radishes grow really well in this area. We’re trying to grow things that are more traditional, like what our European ancestors would have eaten. Cabbages, beets and carrots keep and can be fermented; we can grow them and then store them for the winter.

At the front of our property, we have raised basket gardens called chinampas that were first used long ago in Mexico. We made them out of razor grass, waste branches, compost and other inedible matter and placed them in flooded areas on the property. Inside, we grow the three sisters: corn, beans and squash.

Bryce: We finished building our cob house in the fall of 2009, and life was pretty tough at first. We didn’t have a well and had to take empty bottles in the pedal car to my grandmother’s cabin. So Misty dug a well by hand that year.

Misty: I made the hole three feet across and dug down with a shovel until I got the length of the shovel deep, and then I scooped up dirt with a Maxwell House coffee can. When I got as far as I could, I placed a bucket on a rope between my legs and used my hands to scoop soil into it. Bryce would be up top to pull on the rope, dump out the bucket and send it back down again. I hit water after about eight feet.

Over the years, we learned that some projects required a bigger indoor space, so we had to add to the house. For instance, there was one year when we had tons of potatoes but they froze solid and were all lost because we had no place to store them. When things started to warm up in the spring, we started building. In 2009, we focused on the the primary 10-by-10 house. The mudroom was in 2010. In 2011 we built the outdoor porch, and in 2013, we covered the porch between the outhouse and the 10-by-10 to make the living room.

Bryce: After we built the east wing, a retired contractor said he wanted to see the property and we gave him a tour. The engineering blew his mind. Then, in one joking moment, he said we wouldn’t get an occupancy permit because the design doesn’t have baseboards. And he said we were incredibly brave to build it, by which I suspect he meant that we were brave to stand up to the building department. Before that, I had never even heard of an occupancy permit.

Misty: That was around the time I got pregnant. Bryce and I didn’t always want to have kids. I thought that there was a big population problem and that, if I love the planet, which I do, I shouldn’t have kids. But I started to see that other people who are also very conscious about sustainability were choosing not to have kids for the same reasons. If none of us had kids, there would be nobody to pass on the knowledge of sustainability. We realized that the problem wasn’t overpopulation; it was overconsumption. We decided that, if we had kids, we were going to raise them in a way that was not going to add to the problem. Eventually, we had two girls, Sage and Aurora. They’re two peas in a pod. They are all fun and adventure all day long. They’re very seldom bored, seldom lonely.

When I first got pregnant, it was clear that we were going to need more space. Originally, we were just planning to add one room, but because of a big white cedar tree that is central to the staircase, it was like, Well, either we build a teensy tiny little room or we go beyond that tree to the next set of trees. Now the west wing is our dining room and pantry, and upstairs is the bathroom and spare room.

Bryce: We did some catering for a while to make extra cash. We actually hosted a five-course tasting menu at the local post office, where there was also a little café. It was fantastic—a really good way to make connections in the community. But it was a hustle to break even.

Misty: When I was giving birth to Sage, our eldest, I literally could not pay my bills at all. That was the absolute most difficult moment. I was like, Oh no, am I responsible enough to have a baby? At one point, I felt like I was failing at authentically doing what I wanted to do, and then I realized, Well, you’re constantly going to fail. I decided to reset my goals and focus on what we did have. Even though I was stressed, we ate fine because we were growing all our own food back then. Our house was fine, and that was what cemented this lifestyle for me.

If people had sovereignty over their own living arrangements and access to land, nobody would ever go hungry or lose their homes because they lost their job or got sick. If land were accessible, homelessness wouldn’t be an issue. I don’t think hunger would be an issue. In this area, houses are going for an average of $850,000.

Bryce: Rich people coming from Toronto have pushed up the property values.

Misty: As house prices go up, it’s getting harder and harder for people to afford to live in rural areas. It’s a systemic thing. But our lifestyle takes the edge off all that survival-mode thinking, which is what allows us to feel this abundance mindset.

Speaking of abundance, we have a heck ton of eggs, so I’m making a potato quiche for lunch. Since we’ve had kids, we get one or two grocery deliveries per month. We buy organic fruit for the girls because that’s their treat. We’ve stopped doing catering gigs, for the most part. We pay for everything with the $29 a month we get from our Patreon account and $14,000 a year from the Canada child benefit.

Girls, come to the table for lunch. Aurora is our youngest.

Aurora: I’m 5! All the animals are my favourite.

Sage: I’m 7! I love our food—it’s perfect.

Misty: We like to say a blessing before we eat.

All: May we together bless this food. May we all receive its full benefit, nutritionally and spiritually. May we savour its taste and make full use of the energy it provides. May we in turn feel blessed that we may share this energy in good company and good health.

Misty: The girls love to forage. They’re homeschooled, and last year we did a unit on medicinal herbs. One day, I got injured after falling off a horse. Before I could even hobble to a spot to sit down, Rory went to the garden and picked me some medicinal herbs.

Most of what we do is unschooling, which means that we do our schooling in real-time, all day long, not at a desk. We do a Waldorf approach, so we sit at a desk only for the purposes of writing—we’re currently using Brain Quest notebooks—or doing artwork, and the rest of the education happens in real life. Their biology lesson happens out on the farm. The French lessons happen in conversation when our French-speaking friends visit. Cooking lessons happen in the kitchen. The girls are presently in kindergarten and Grade 1.

I think a lot of people are like, “Oh, homeschool. Oh, alternative lifestyle. You’re sheltering.” No, our friends have kids and we get invited to a lot of things. The girls go to birthday parties and festivals in the community. We also volunteer with a local Waldorf school, and we’ve had the class out many times to learn skills. It’s traditional for Waldorf schools to have a bread oven made of cob, so because our kids have been around cob so much, they taught their kindergarten peers all about it and made a lot of friends that way.

For now, they like being here. And they like this lifestyle. If all they learn is how to do this, I feel like they’re prepared for the world. If next year Aurora says she wants to go to school, we’ll send her to school. It’s her choice.

YouTube is like our TV. When the girls do their schoolwork or they do a good job in the garden or whatever, they get video points, and they can have a YouTube video for their video points. They love musicals.

Bryce: On our YouTube channel, called Ontario Permaculture, we did a video called “Fantastic Feasts and Where to Find Them.” We taught the girls about foraging for wild leeks.

Misty: I think a lot of the people who are getting into sustainable living don’t have access to the same amount of leisure time or research skills that we had early on, so we try to fill that niche with our YouTube channel. We get so many questions: How can I grow my own food in a small space? How can I make my lifestyle more sustainable if I don’t have access to land? What are some steps I can take to prepare myself for off-grid living? There are these people who say, “I’d love to do permaculture, but I’m in Toronto in an apartment building. What can I do?” And we tell them it’s not about the practices; it’s the mindset. How can you eliminate waste?

For 11 years, I’ve been writing openly about our house for the local paper, BizBull, which is free and delivered to mailboxes in this region. In 2018, I wrote about the west wing addition and I mentioned a mud and straw basketweave that we add to the cob as infill. A few months later, I have a toddler on one hip and a baby on a boob, and I see four men at the end of our driveway. The road was blocked by their parked cars. It was a bit terrifying because one of them looked like he was in uniform.

Bryce: I went down there to talk to them, and these four guys were like, “We’re here to do an inspection of your home. We hear that you’ve got something going on back here.” And I’m like, “We’ve got the place where we live and you might want to call it a building, but it’s not that.” Because, as the Southgate Township official told us before we built our house, the 10-by-10 structure was not a building under the law. And our additions wouldn’t need a permit either because you can’t add on to something that isn’t legally a building. But the officers were like, “That’s for us to decide.”

A permit would cost us roughly $15,000. I asked what they would do if we couldn’t afford that. Would they tear it down? They said yes. I told them we’ll see what we can do about the money for the permit. After they left, we learned that the official we’d originally consulted wasn’t with the township anymore and a new one had come in with a tougher approach. At the same time, the township claimed it had received an anonymous complaint after one of Misty’s articles ran in the paper, which we think is what spurred the surprise visit.

Misty: Let’s be clear, though: I would not have been representing our life quite so candidly if I thought I was doing something illegal. Our next-door neighbour is a town councillor. We were in a play with the mayor and he came to pick us up here, so it wasn’t like we were hiding. And the thing is, since those four men came to our property, the township has been really vague when answering our questions. So they’re like, “It’s for safety. It needs to be permanent.” And I’m like, “What specifically is the issue?” “Well, no, no, no, there’s no specific issue.”

Now, there are lots of things I could see that an inspector wouldn’t like about our house—the earth-connected foundation, for example. And there are lots of things I would like to be better, like the ceiling, which isn’t well-insulated because we haven’t found a good, sustainable, non-toxic material to use. But I was a homeowner at 20, and all houses have drawbacks. The second a house is approved, the homeowner takes over and they do all kinds of unsafe things. People make repairs and alterations that inspectors don’t know about.

Bryce: Later, the township left an application form for a permit in our mailbox, and as we’re reading it, we realized we couldn’t fill it in. In the form, you have to attest to the truth of everything in it, but there’s one section that asks the purpose of this application: new build, renovation, demolition, and so on. But it was none of those things, so if I checked any of those boxes, I’d be lying.

Misty: Also, the deadline for the application was impossible. They said we had 10 days to send engineered blueprints, but we talked to an architect who said they could not produce a retroactive architectural drawing of any dwelling that fast. So we negotiated 30 days, but the township wouldn’t let us see the building code without paying a $300 fee. It’s like, well, if you don’t have that $300, what do you do? I asked if we could come look at the building code at their office, and they said no.

I asked for help. I’m like, this is a really overwhelming experience. For several months we had a back and forth with the township’s lawyer, and finally we said we couldn’t move forward with the application because they weren’t answering our questions. Then they filed an application with the court.

We started a GoFundMe to finance our defence, and as soon as it hit $1,000, which is what we needed to get going, we closed it. When we went to court, the judge said he couldn’t stamp the application because he needed more information. We’re now at the discovery phase of an action. We’re being sued. If we can’t afford the permit, the township could ask the judge to issue a demolition order.

If they demolish our house, I could just build another shelter in a month, and the fact of the matter is, I would. I love cob. It’s part of who we are, and I wouldn’t want to live in another type of house. But we can’t afford to lose. The amount we would owe would be added to our property tax, and if we fail to pay that in full within two years, the township can repossess our property.

We will not go back to working for things that we know are detrimental to human life and sustainability. And I’m definitely not ever going to live in an apartment in the city. If I were down to my very last penny and my only option was panhandling in Toronto, forgive me, I wouldn’t do it. We would rather break from society’s expectations than go back to the rat race. So, in one way, this case has increased my resolve, but it’s also made me kind of lose faith in the municipal model.

Bryce: It makes me more aware of the difficulties that people go through because we did this for 10 years with no problems and no flak. For it to become an issue spontaneously demonstrates that the system is banked against the average Joe.

Misty: We are countersuing for malfeasance and the harm of all these years going through this process. It’s been hard on our marriage. It’s been hard on our kids. But we have used the adversity to our advantage. It taught us to stay tough, and now I’m teaching my girls about the Canadian Constitution, about our rights as citizens.

Bryce: It’s as if we’re trying to live in the Game of Life, but people keep choosing Monopoly.

Misty: The law guides people to think that Monopoly is the only game you can play. You can either lose or you can win. I think this lifestyle shows that there is another way possible.

This story appears in the July 2022 issue of Toronto Life magazine. To subscribe for just $39.99 a year, click here. To purchase single issues, click here.