A Cultural Revolution: the AGO’s Ai Weiwei exhibition proves why the Chinese artist is such a threat

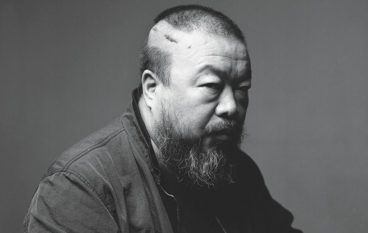

Ai Weiwei is the most famous artist on the planet, and like many who have held the title before (van Gogh, Picasso), his personal story may be better known than his art. Over the past five years, he has become China’s leading dissident, endlessly harassed and attacked by state authorities for creating work that seeks out the limits of expression in a country not big on the concept of artistic freedom. In him, the rebellion and the art, the life and the work, are one and the same.

Ai was born in Beijing in 1957, but grew up far from the capital after his father, a prominent poet, was denounced as a traitor to China’s revolutionary ideals and sent to live in a remote province. He spent most of the ’80s living in the U.S., studying design in New York and playing blackjack in Atlantic City. (He is considered one the game’s top players.) His career as an avant-garde artist and designer began in earnest after he returned to China in 1993 to care for his dying father. His breakout moment came in 2000 with a group show he co-curated in Shanghai called Fuck Off, which featured one artist fasting for days, another floating down a river inside a bubble while wearing a diaper and, most notoriously, a series of photos of an artist cooking and eating what looked like (and very likely was) a human fetus. Ai contributed photos of himself giving the finger to the White House and Tiananmen Square, as well as dropping and smashing a 2,000-year-old Han vase.

Ai’s troubles began in the same year as the Beijing Olympics, with the massive earthquake in Sichuan province that killed 90,000 people and left millions homeless. Thousands of children were crushed in the rubble of their shoddily built schools—a fact the Chinese government tried to cover up. Ai responded to the scandal with works of art: using backpacks to represent the children who died in what became known as the “tofu-skin” schools, he created a 150-foot-long snake. Snake Ceiling is part of a touring exhibition that opens this month at the Art Gallery of Ontario called According to What? It’s the first major North American survey of Ai’s work. The AGO is determined to keep the collection’s political meanings in the foreground: on the opening weekend, members of the public will read out the names of the dead schoolchildren.

For his act of artistic memorialization, Ai was beaten so severely by Chinese authorities that he had to undergo emergency treatment for a cerebral hemorrhage. Since then, the government has fined him, kept him under constant surveillance, destroyed his Shanghai studio, barred him from leaving the country, imprisoned him on charges of tax evasion and accused him of spreading pornography.

Ai has reacted to his ongoing persecution by becoming even more outrageous and outspoken. He photographed himself nude, a stuffed animal barely covering his genitals. (The photo’s caption formed a crude, anti-authoritarian homonym in Chinese—hundreds of Ai supporters posted their own versions of the image on the Internet.) He recently released a hard rock album that directly references his time in prison. And he made his own “Gangnam Style” video, in which he puts on handcuffs and dances around like a bearded, heavy-set Psy.

Ai’s notoriety and meme-generating antics have led some critics to dispute the value of his art. Some believe his fame as a dissident distracts from his status as a great artist, others that his fame camouflages the banality of his art. Both arguments miss the point. Ai’s paintings and sculptures are dangerous challenges to power. The poignancy of the snake made of backpacks comes not just from the horrible event that inspired it, but also from the fact that the Chinese government felt so afraid of it that they had to beat up its creator. Politically charged art is a real threat to repression, and the government knows it.

Ai could live comfortably in exile in the West. Instead he remains in China, to be tormented by his government, to force them to show their hand. Like the novelist and blogger Han Han and many other artist-dissidents who have refused to live in exile, Ai pushes the limits without calling for the overthrow of the existing system. Resistance is the core of his practice. Each of his sculptures reveals what the Chinese government will or will not allow to be displayed. This is not merely art that makes a political statement; it is art as a form of politics, and the best of Ai Weiwei’s works erase the distinction between the two. When he was under house arrest for a tax bill, his supporters folded money into paper airplanes and threw them over the walls of his Beijing compound. It was true protest and perfect performance art all at once.

Almost by accident, Ai Weiwei has formulated a surprising answer to the age-old yet still-pressing question of whether art really matters. In his world, art matters more than anything. It rides into the darkness of oppression and illuminates it. That is the greatest lesson in According to What?: art is even more dangerous than dissent.

Ai Weiwei: According to What?

Art Gallery of Ontario

Aug. 17 to Oct. 27