Thirteen fascinating artifacts about booze and gambling in turn-of-the-century Toronto

Turn-of-the-century Toronto was a very different city from the one we know today: booze was a hot button issue, children as young as 11 were imprisoned in the Don Jail and sleazy rags were the only place to find information on gay culture. That bygone era is documented in Vice and Virtue, an exhibition at the Toronto Reference Library’s TD Gallery, on until April 30. “It’s a light-hearted look at moral reform in ‘Toronto the Good,’” says Mary Rae Shantz, the manager of service development for the library’s special collections. “Nowadays, we place moral judgments on the same themes—smoking, legalization of marijuana, the sex trade—discussed in the late 19th and early 20th century. The more things change, the more they remain the same.” Here, the stories behind 13 artifacts in the show.

Gooderham and Worts

Arthur Henry Hider • 1896

The Gooderham and Worts distillery was the largest whiskey factory in the world in the 1860s. “Alcohol was big business in Toronto,” Shantz says. “Alcohol was the centre of social life, generating profits that contributed to charities and city-building projects. You wouldn’t be able to imagine a Toronto with infrastructure not created by this industry.” At the same time, over half of all arrests in the 19th century were for booze-related offences.

The Red Lion Inn

Owen Staples • 1912

The Red Lion Inn was one of Toronto’s first and most significant buildings, erected in 1808 near Yonge and Bloor, which was surrounded by wilderness at the time. The village of Yorkville sprung up around it and a community was forged. “The inn was used as a polling station during elections, circa 1830s,” Shantz says. “Taverns weren’t just a place to drink absinthe—they were a meeting place for town halls and court sessions.” The inn closed in 1892.

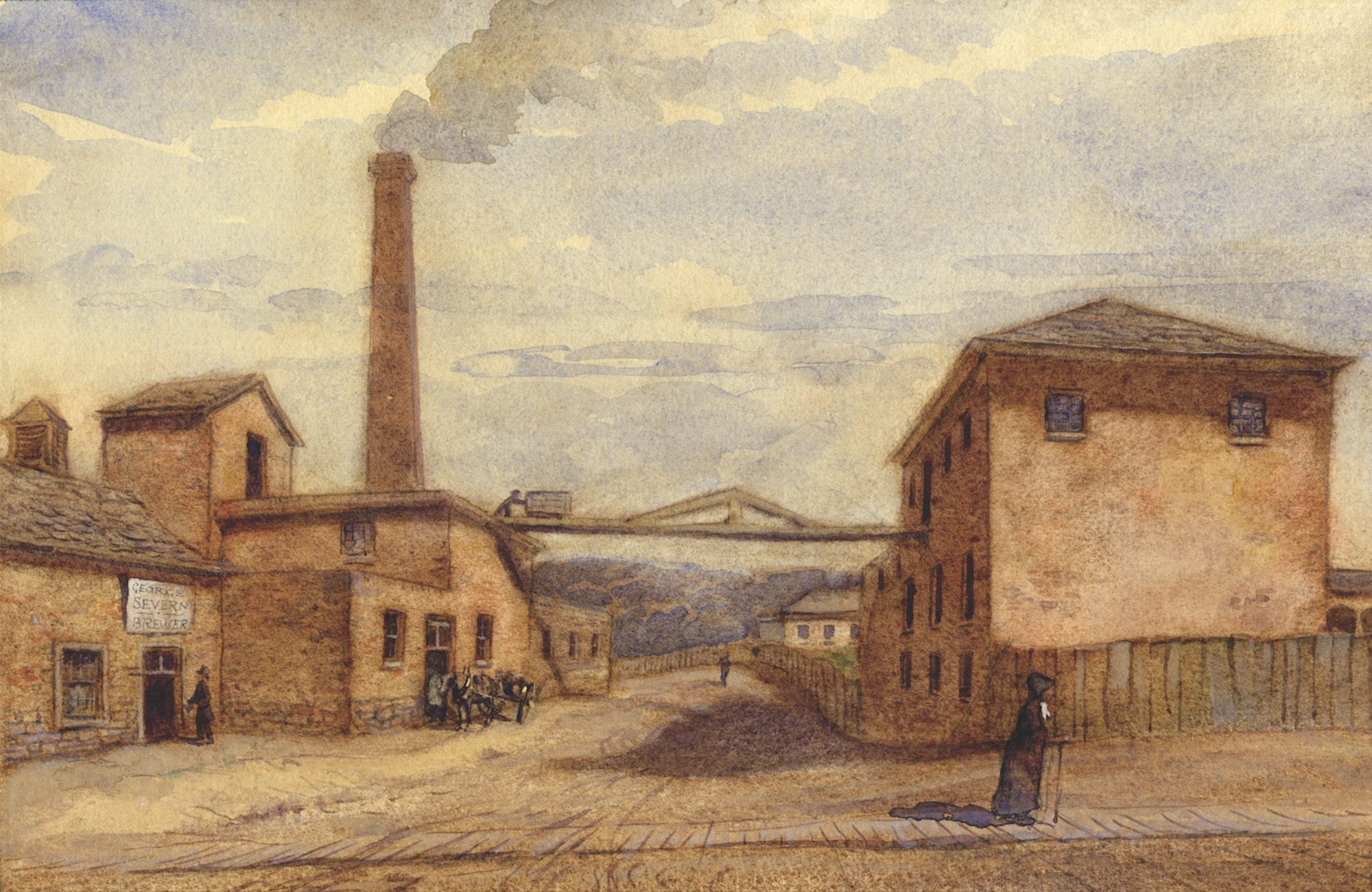

John Severn Brewery

Frederic Victor Poole • 1912

“When [Yorkville village councillor] John Severn’s brewery was built in the 1830s, nobody thought twice about alcohol,” Shantz says. “But 100 years later, it was like the great evil. Our city had a love-hate relationship with alcohol.” The brewery was located north of what is now the Toronto Reference Library and brewed 26,500 litres of alcohol every week. It’s the reason Yorkville’s coat of arms features a beer barrel and the letter “S.”

Highlander Malt Extract Label

Toronto Produce Limited • Circa 1930s

In 1916, the Ontario Temperance Act outlawed the sale and consumption of alcohol, but not its manufacture. “When you bought malt extract in the 1930s, there would be a silver label that would say something like ‘crude molasses,’” Shantz says. “Producers tried to disguise the true use of the product, but if you scraped it off, you would find a recipe for making beer underneath.”

Temperance Lesson No. 12

Dominion Scientific Temperance Committee • Circa 1912

The Dominion Scientific Temperance Committee used science and Shakespeare to warn of the “evils” of booze. This is one of 12 posters produced by the committee and the Prohibition Federation of Canada in 1912, which feature some dubious facts and figures about the effects of alcohol on the body. “They were distributed in public schools and clearly target a young market, aiming to prevent–not stop–drinking,” Shantz says.

Toronto Gaol Registry

Top: 1884; Bottom: 1874

When the Toronto Gaol, also known as Don Jail, was built on the eastern shore of the Don River in 1864, it was the largest jail in North America. “Drunkenness and larceny were the two biggest reasons people were picked up,” Shantz says. “[In this registry], you find all sorts of interesting details: age, religion, race, trade, rank in life. It just goes on and on.” This page includes those incarcerated in July 1874, including men, women and children as young as 11, all recorded as being of the “lower class.” Another registry, called the Punishment Book (1947-1960), is confidential until 2040 because some of the prisoners are still alive.

Of Toronto the Good: A Social Study

C.S. Clark • 1898

Toronto the Good has been all but replaced by more modern monikers: Hogtown, T.O., the 6. But the nickname—coined by 1880s mayor William Howland—served as the title of a sensationalist exposé of drunkenness, gambling and prostitution in the city. The author argues for the legalization of prostitution.

Greenwood Race Track

1924

Race track betting, which was associated with high society, was legalized in 1910. This shot is from the Classic King’s Plate Race at the Greenwood Race Track, then known as Woodbine Race Track. “At the time, horse racing was a socially acceptable form of gambling—the queen did it for crying out loud,” Shantz says. “On the other hand, backroom games were looked down upon as being immoral. There was a double standard.”

Sunday Laws

The Lord’s Day Alliance of Canada • Circa 1911

In the early days of Canada’s industrial era, people were divided on whether Sunday should be a holiday—or, a holy day. The Lord’s Day Alliance, an organization founded by the Presbyterian Church, persuaded then–prime minister Wilfrid Laurier to introduce a federal Lord’s Day Act in 1907, which prohibited trade, labour, recreation and most commerce on Sundays. They also unsuccessfully lobbied against Sunday streetcar service. “If you open up streetcars, gosh, people won’t stay home and observe the Lord’s Day,” Shantz jokes. “The act was repealed in 1985. It’s interesting how long these blue laws persisted. In 1986, it was still illegal to go shopping on a Sunday.”

Victoria Industrial School

Industrial School Association of Toronto • 1898

In 1874, Ontario passed the Industrial Schools Act, which was intended to “rescue” children found guilty of petty crimes and moral offences. This photo shows 110 students, aged 10 to 14, doing physical drills at the Victoria Industrial School, the province’s first reform institution for boys. “One of the leading reasons you would end up there was poverty, which was very sad,” Shantz says. “There was this idea that juvenile offenders came from ranks of street hawkers—and the idea that solid recreation and discipline could put anyone back on their feet.” In 1934, the facility closed and all the students were transferred to Bowmanville Boys’ School. In the 1970s, the property became the Mimico Correctional Centre, which was demolished in 2011 to make room for the Toronto South Detention Centre.

Child Protection Act

Department of Neglected and Dependent Children of Ontario • Circa 1893

Just after the Victoria Industrial School opened, Ontario passed its first Child Protection Act, making the neglect and abuse of children a criminal offence. “Social crusader and newspaper reporter J.J. Kelso was involved in making that significant piece of legislation,” Shantz says. “He was active in creating care agencies, advocating for children. In 1891, he founded Canada’s first Children’s Aid Society.”

Is Your Own Daughter Safe?

Hush Newspaper • 1930

“In the 1930s, tabloids like Hush were the only place to find info on gay subculture,” Shantz says. “Hush was alarmist and popular, reporting sensationalist news that no one was else was reporting: divorces, businessmen caught in lurid situations and the ‘white slave’ trade.” Its competitor was Flash, which also covered topics deemed taboo by the mainstream press.

Roxy Follies Ad

Hush Newspaper • 1931

In 1919, the 500-seat Globe Theatre opened on Queen Street West. It specialized in vaudeville and B-movies, but started offering “girlie shows” when it was renamed the Roxy. Polite society frowned upon the offering. In 1961, after months of public debate, a new law permitted live theatre on Sundays, including burlesque.