Cranky empty nesters, party-loving hipsters and screaming babies are living cheek by jowl in downtown condo towers. How the vertical city became a generational combat zone

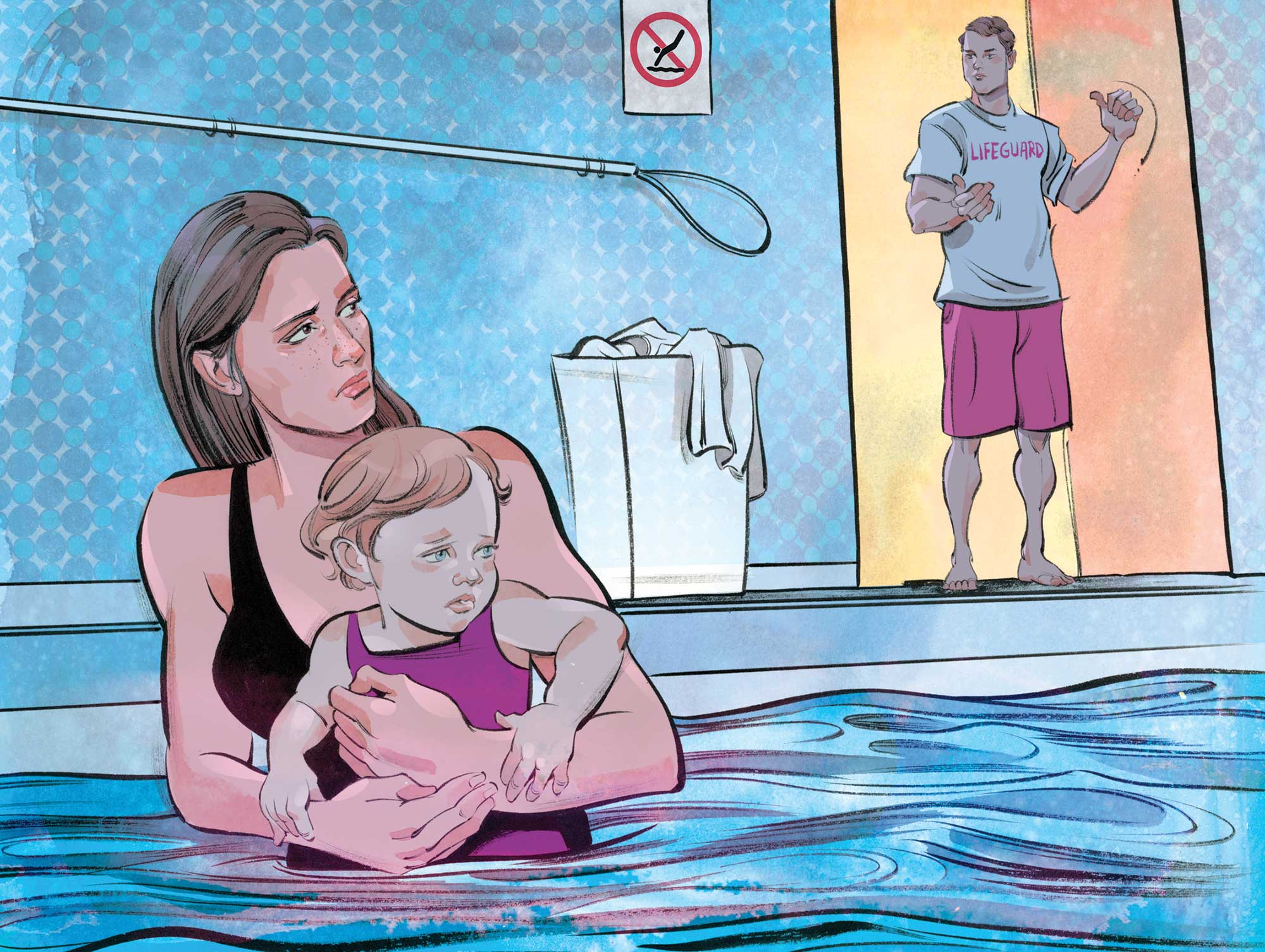

It was a beautiful day in June 2008, and Michelle Pantoliano wanted to take her 10-month-old daughter to the pool. Pantoliano, a young mother living in a condo on Islington Avenue in Etobicoke, gave the baby a bath, dressed her in a swim diaper and bathing suit, and carried her down to the pool deck. But a few minutes after they slipped into the water, a lifeguard approached. Babies weren’t allowed in the pool, he said. Pantoliano wasn’t aware of such a rule, but she reluctantly agreed to leave. Shortly after, she called the property manager and left a voicemail. When she didn’t hear back, she assumed the lifeguard had been misinformed.

Over the next couple of weeks, Pantoliano tried to take her daughter to the pool twice more. Both times, the lifeguard shooed her away. On her final visit, another mom and baby were also in the pool. When the lifeguard tried to get them to leave, the other mom refused—and the lifeguard called the property manager to intervene. When he arrived on the pool deck, he pleaded with the women to get out. It was all turning into a scene: the powerless lifeguard, the supplicant manager, the defiant moms.

In the middle of the fracas, Pantoliano asked the property manager to explain what the regulations actually said. The condo corporation’s Rule R3.1–5, he replied, stipulated that “persons requiring diapers,” specifically kids two and under, were banned from the outdoor pool, indoor pool and whirlpool. If Pantoliano had a problem with it, she’d have to take it up with the condo board.

Instead, she filed a grievance with the Ontario Human Rights Commission, on the grounds that the condo’s rules discriminated against people with kids. In response, the board consulted a lawyer, who advised that the ban be suspended. The melee should have ended there, but logic took a back seat to territorialism. In a vote, the mostly elderly residents rejected the lawyer’s proposal.

Once word got out that it was Pantoliano who had started the mess, she started to feel unwelcome in her own building. She attended a condo barbecue that summer with her husband and baby—disregarding the memo that it was “ADULT RESIDENTS ONLY!”—and everyone ignored her. Another time, when Pantoliano was talking to her cousin on the pool deck, a man told her to shut up. “No, you shut up,” she shot back. In the condo newsletter, “Suite Talk,” board president Liesl Bandler attacked Pantoliano’s conduct. “Unfortunately, there are a very few residents who are inconsiderate of their neighbours and who consistently break the rules,” she wrote. “It is your Directors’ fervent hope that these people will realize their anti-social behaviour and will change their attitude.”

It took three years for the case to reach a human rights tribunal; by the time it did, Pantoliano and her family had moved out of the building. Several neighbours testified against her; one presented tidbits found on the Internet about the dangers of E.coli. The tribunal waded into information on urine counts and fecal pathogens, plunged into diarrheal conditions like Shigella sonnei and Campylobacter jejuni bacteria, and confirmed that chlorine kills pretty much everything gross in a pool.

Tribunal vice-chair Naomi Overend found in favour of Pantoliano, and the corporation was forced to repeal the ban. There was no medical, safety or other reason to keep kids out of pools. It was a clear-cut case of one generation holding on to its antiquated privilege. The condo was originally marketed as an adults-only complex, and many owners had bought their units because they were promised the quiet comforts of empty nesters. In the end, the board was forced to pay Pantoliano $10,000 in damages for emotional hardship.

Pools have long been condoland war zones. In 1990, a father filed a claim with the Human Rights Commission against his Scarborough building for restricting pool access for his school-aged daughter; eight years later, he won the claim. More recently, a father of two teenagers successfully argued at a tribunal that his condo discriminated against families because it had signage calling it an “adult lifestyle building” and also restricted kids from using the pool at certain times.

Lifestyle clashes are inevitable when people of all ages and socio-economic backgrounds live on top of each other in a forced community. When different priorities collide, a siege mentality can set in. In the years since Pantoliano’s case, Toronto has sprouted tens of thousands of new condo units in every shape and size. Retired empty nesters live below boisterous hipsters. People who work night shifts are trying to sleep while parents are getting their toddlers off to daycare. Families with rowdy kids take up residence across the hall from quiet professional couples. And they all unrealistically expect the same degree of freedom and privacy as they’d have in a detached home. Instead, they’re keeping each other up at night, squabbling in hallways, sparring in elevators and petitioning condo boards. The shimmering vertical city has become a breeding ground for lawsuits, bullies and brawlers.

I’ve lived in a midtown condo for the past 17 years. My building went up in the mid-’80s, at the beginning of a 10-year period during which close to 60,000 high-rise units were built in Toronto. There’s nothing picturesque about the brown, brutalist façade, but inside is a surplus of space: the units range in size from 1,450 to 1,780 square feet, larger than many Leslieville semis, and roomy enough to comfortably raise my eight-year-old son and store all his Lego. I have two massive bedrooms, 12-foot ceilings, an eat-in kitchen, unobstructed views of the Rosedale ravine, two full bathrooms and a walk-in closet so spacious that I once considered turning it into a home office. The walls are poured concrete, and the windows are supported by steel framing and quality masonry. When my unit was built, the city was in its condo infancy, and the affluent downsizers who were moving into units expected those kinds of details.

The condo boom of the past decade was fuelled by a dearth of land downtown, historically low interest rates, and Torontonians’ growing desire to live near entertainment and work. In the 2000s, the city’s official plan designated the downtown core as a growth area, and the province aimed to curb urban sprawl with the Places to Grow Act. As a result, between 2003 and 2013, 118,000 new development applications were filed for the core, with many buildings targeting young professionals looking for a starter home near the TTC, nightlife and the Financial District.

As housing affordability plummeted, condo ownership diversified. The average price of a semi-detached home in the city of Toronto is around $856,000. For an 800-square-foot condo, it’s $427,000. The pool of buyers in the lower bracket is vast and varied. Only 20 per cent of condo owners in Toronto are under 35. Roughly a quarter are seniors, and the rest, about 55 per cent, are in their 30s, 40s and 50s, well into their child-rearing years.

To keep up with demand, new complexes downtown are usually designed with as many units as possible. The more units a developer can cram in, the more he can sell. For residents, more units means more noise. In my condo, there are only four units on each floor, and each sits on top of its twin. My bedroom is over the downstairs neighbour’s bedroom; my living room is above his. When we’re sleeping, chances are he is, too. In the new builds, however, developers often create interlocking Tetris-style floor plans to maximize space. Some of the towers in the downtown core have upwards of 70 storeys and 1,000 units. The upper floors may have four units each, like in my condo, but the other 60-odd levels can have as many as 24 suites and dozens of floor plans.

Another way to maximize profits: tiny units. The average new Toronto condo shakes out at 849 square feet, down from 900 in 2009. Families are forced to convert closets into kids’ rooms. The problem isn’t a lack of inventory. For the past several years, the city has required many new condo developments to include family-sized units of two or three bedrooms. But they’re premium-priced, and many families can’t afford to live in them. I spoke to the city’s chief planner, Jennifer Keesmaat, about the problem. “These units are often being occupied by six students, or five young professionals who have pooled their resources to buy a three-bedroom condo,” she told me.

In the spring, the province proposed inclusionary zoning, which would allow cities to force developers to include a certain percentage of units at prices below market rate. It’s an astonishingly logical move, though it will take years before council hammers out the details and Torontonians reap the benefits. For now, we’re packed like pickles in a jar. If you ask condo property managers about the kinds of complaints they deal with on a given day, the vast majority come from the noise that percolates throughout the building: renovations, loud music, the sound of toddlers dropping toys on a hardwood floor. In B.C., one family of four was fined by their condo board because their kids were jumping around too much. Toronto may not be far behind.

Karen and David are part of a burgeoning cohort of parents who rent condos in the city. They both work in media, and they agreed to speak to me on the condition that I don’t reveal their real names. Three years ago, when their son was a toddler, they moved into a 900-square-foot unit in a placid low-rise in the west end with just under 100 suites. They love the building, but the unit isn’t designed for a family. There’s only one bedroom; for a second one, they retrofitted an alcove barely big enough to squeeze in a kids mattress. They stacked some Billy bookcases from IKEA together to turn it into a space for their son.

A couple of days after moving in, Karen and David met their next-door neighbour, a middle-aged entrepreneur. At first, he was pleasant to Karen. But the relationship took an ugly turn a few months later. “The neighbour came knocking on our door,” Karen recalls. “He said, ‘I don’t know what you guys are doing but I can’t stand it. I can’t sleep. It sounds like you’re bouncing basketballs all the time.’ ” He’d been bottling up his rage for a while—he said he’d been unable to take his 6 p.m. “power nap” for weeks. Karen was profusely apologetic and promised to get to the bottom of it.

Then texts started pinging her phone. At first it was one message every week or two, each time from the superintendent on behalf of the neighbour. They all said the same thing: stop the noise, stop the noise, stop the noise. Once, Karen’s son fell ill and was crying all night. The next morning, her husband came out of their place and saw the neighbour yelling at a mother of two young girls down the hall, about the fact that their dog was barking at night. “He was shouting,” Karen says, “and the minute he saw my husband in the hall, he turned and said, ‘And you! You with your crying baby!’ ”

Soon after, the property manager inspected Karen’s apartment and noticed that the baby gate was attached to the wall abutting the neighbour’s bedroom—their son had a habit of rattling it, and Karen realized that was likely the source of the noise. She rearranged the fixtures, but the guy next door continued to complain. He would glower at her in the hallway. She even heard he’d hired a lawyer. “Now he was spending money to find anything he could to use against us,” Karen says.

One day, the super texted Karen and asked her to come up to a meeting in the party room. The police had been called in to deal with the conflict and wanted to speak with her. The officer asked how much noise she and her family were making, but overall he was sympathetic. He told Karen that the neighbour had every right to complain, but that she should let the police know if the neighbour ever harassed her.

The thing about noise is that once you become aware of it, you can’t tune it out. That’s what happened to a woman I’ll call Anne, a former executive assistant who retired last year. She lives in a downtown mid-rise, next to a family with a young boy who had a habit of running loudly around the apartment all day. Anne started hearing the noise shortly after she stopped working and was spending more time in her condo. “I felt guilty about saying anything,” she says, “but the running was constant—it sounded like rats scurrying across a floor.”

When she alerted the property manager, he told her to keep a log of each time she heard the sound. “That made it even worse,” says Anne, “because I was always looking out for it.” This summer, the building managers and the boy’s parents went through mediation to deal with the noise complaints. Anne and another neighbour attended the session. The parents noted that the boy would soon be going to school, which would minimize the noise. The building also agreed to explore the possibility of bringing in an engineer to install noise buffers.

You’d expect the footsteps of a toddler on parquet flooring to affect the suite underneath rather than next door, but acoustics can be unpredictable. Brady Peters, an architect who teaches at U of T’s Daniels School of Architecture, told me that sound behaves like liquid: it seeps through every crack and travels around corners. What’s more, sound isn’t considered a relevant or quantifiable commodity in the condo market. All prospective buyers look at floor plans and finishes, but they don’t ask for sound studies.

To make matters worse, it’s extremely difficult for architects and builders to ensure quiet. Impact sounds from heavy footsteps and the thud-thud of a basketball transfer through the partitions between units. Airborne sounds—voices or music or barking dogs—are more reverberant in spaces made of concrete and glass. Both types of sound can result in flanking noise, which transmits through the fabric of a building, over and in between spaces like electrical sockets, vents and floor gaps.

In my building, with its concrete partitions and high-quality finishes, I never hear noise from other units. Not every condo follows such exacting standards. I spoke to one Toronto architect who told me that the minimum requirements of the Ontario Building Code have not been high enough to keep noise from spilling from one unit into the next (although both the federal and provincial codes are in the process of updating their sound transmission regulations). Much of the flanking noise that people hear in condo buildings comes from “built-up assembly”—barriers that are made of infill components, like steel studs, drywall and insulation. “These materials meet the building code,” he says. “But the way they’re put together can easily let noise through.” If the walls aren’t sealed properly, sound will always find the path of least resistance.

The squabbling in Toronto’s cramped condoland has grown so common that an entire cottage industry has sprung up, devoted to resolving condo disputes between neighbours, owners and boards. Jennifer Bell, owner of the mediation company Placet Dispute Resolution, has spent much of her career involved in resolving cases like Karen’s and Anne’s. Under Section 132 of the Ontario Condominium Act, any disagreement between the condo corporation and owners regarding rules or bylaws has to go to mediation and, if necessary, arbitration for resolution. In other words, Bell comes into the picture around the time civil conversation breaks down. Sometimes the condo corporation pays her fee. Usually, the two opposing parties share the cost.

In one recent case, two units were stacked right on top of each other. One belonged to a young single man. He worked shifts as a security guard, came home at 8 in the morning and tried to sleep. The other owners were a family with three small kids. Just as they were starting their day, he’d be nodding off. In the beginning, the family responded to the noise complaints by putting down those spongy puzzle-piece kiddie mats to muffle the impact, but it only covered an eight-by-10-foot patch. The grievances continued. “The family felt oppressed because they were being portrayed as a nuisance,” Bell says. “Meanwhile, the other owner felt nobody cared about his peace and quiet.” The mediation session helped get the owners talking. “When you sit down at a mediation table and you see a real and well-meaning person on the other side, your position usually softens,” she says.

In addition to neighbourly disputes, Bell frequently mediates scraps between condo owners and boards—usually over rules surrounding noise, pets, smoking and, lately, Airbnb rentals in the building. “Boards are essentially a fourth level of government,” says Bell. “They’re allowed unique rules. They have their own governance structure. They’re multimillion-dollar not-for-profit companies.”

By law, each building must have an elected group of representatives, or a condo board, to manage the assets of the corporation. According to the condo act, members have to be mentally capable adults; all other eligibility requirements are left up to the boards. Some boards manage maintenance of the building, but most employ a property management company to conduct the day-to-day operation—security, garbage, repair work. The condo board determines specific rules: whether owners can have a barbecue on the balcony or a welcome mat outside the door, the type of carpeting in the hallway, and, yes, who’s allowed in the pool.

I could cite a dozen reasons why this is a terrible setup. The biggest problem is the fact that a great deal of power is placed in the hands of so few people. Serving on a condo board is a time-consuming volunteer job, and in many cases positions are filled by acclamation. Because so few owners put their hands up to run, the jobs are often given to anyone who wants them. That leaves the crucial decision-making governing the building’s financial health in the hands of fate. Chronic meddlers, megalomaniacs, axe-grinders and agenda-pushers can slide in, no questions asked.

“Some boards are filled with directors who don’t have the knowledge, training or experience to manage an institution that is worth millions of dollars,” says Rodrigue Escayola, a partner at Gowling WLG and an expert in condo law. Escayola has served three consecutive terms as a director in his building (always by acclamation). He spends several hours every week dealing with condo-related issues. “It’s a thankless job. Nobody tips their hat to you in the elevators. Nobody gets you a bottle of wine at Christmas.”

A few times, he’s had to find resourceful ways for his board to deal with neighbour disputes, including when a resident raised the ire of his neighbour by setting up live traps on his balcony to deal with a squirrel problem. The owner claimed that he was adhering to provincial regulations regarding pest control. His neighbour believed he was causing undue distress to the squirrels. Escayola didn’t want to get into a debate over squirrel rights, so he reminded the owner that the condo’s declaration states that balconies can contain only plants and outdoor furniture, not animal traps.

Boards are often generationally homogenous, which can create a ruling bias against other groups. Friends recruit friends to run for positions, pushing through rules that benefit the most vocal constituents rather than the population at large. It’s common to see a board full of retirees, because they’re typically the ones who have time to volunteer for the job.

In some buildings, directors don’t even have to live in the complex to serve on the board. They might include an absentee investor who uses his role to make as much money off the building as possible. Board members with their own financial motives have run into trouble with the law lately. Escayola was a lawyer in a 2015 case in which investors were renting out single units to multiple university students, contrary to the condo’s declaration, which said that each unit had to be occupied by a single family. Nearly 22 per cent of the condo consisted of such units, many of which had locks on all the bedroom doors, turning them into makeshift rooming houses.

A tense standoff ensued between the landlords and other neighbours who wanted the board to crack down on the regulations. The board tried to pass a rule to grandfather the existing rentals for a period of 10 years. When it went to court, the judge came down hard: directors shouldn’t be torquing the system for their own financial gain. The judge upheld the declaration’s single-family stipulation, ordered the board to pay $35,000 in legal fees and demanded that the president pay an additional $15,000 in damages.

So why do things break down? Because all residents, especially those of different socio-economic strata—whether they are students or not, professionals or not, have kids or don’t, are investors or not—have competing priorities. And condo boards aren’t trained or equipped to deal with these issues. Everyone has a right to the quiet enjoyment of their home—that very principle is enshrined in most condo board declarations. The only problem is that no two people on the planet have the same definition of what that means.

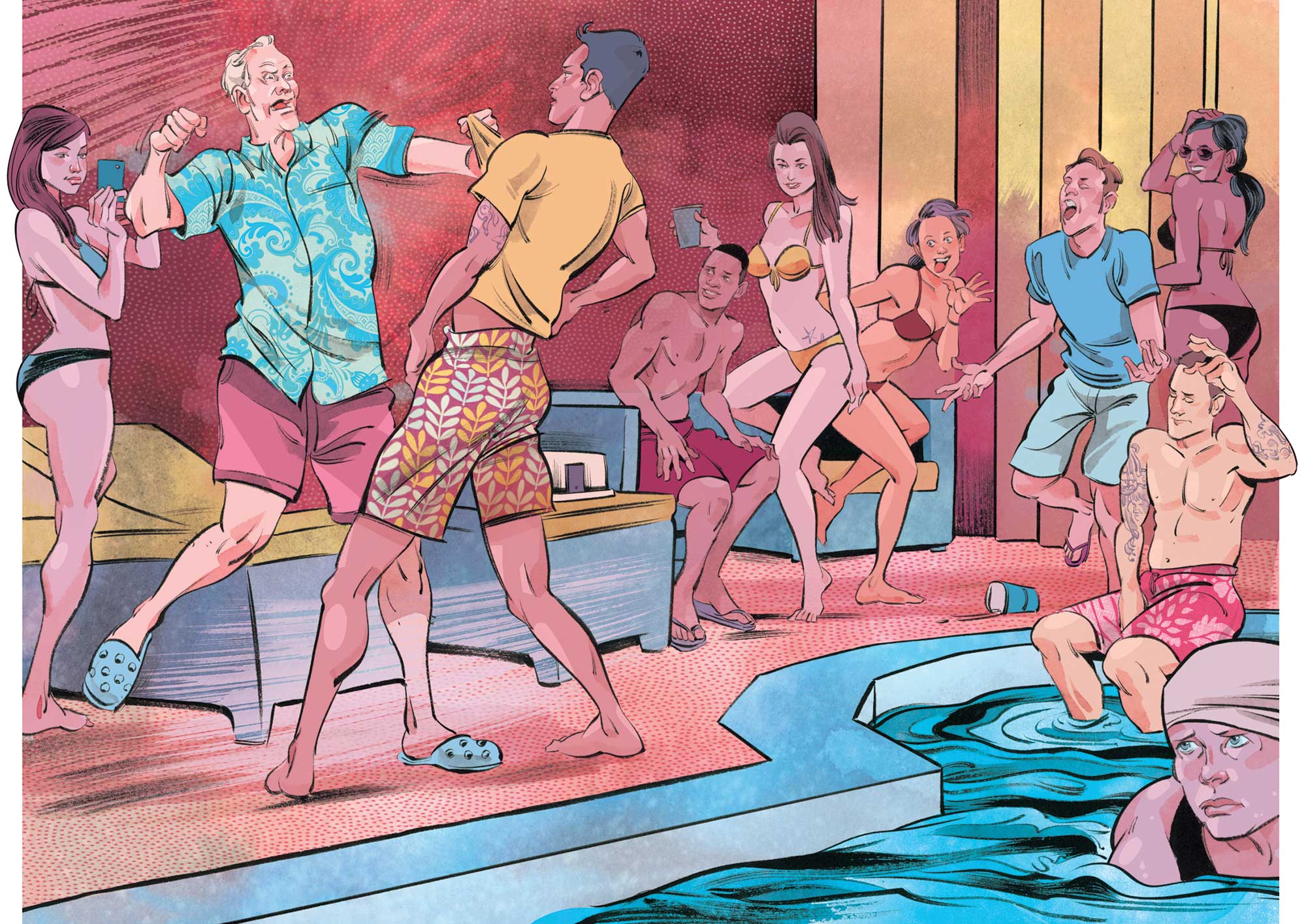

In 2014, Allison, an executive at a tech start-up who has a young son, rented a unit in a swanky 27-storey condo tower located near the water and close to transit. It was modelled after a five-star Miami hotel, with gleaming white marble floors and postmodern furniture in several shades of charcoal. There were two swimming pools, a gym, a billiard room, a yoga studio, and courts for squash and basketball.

Shortly after moving into the building, Allison began to regret her decision. Her next-door neighbours cranked their music and regularly partied until two or three in the morning. Sometimes, their guests would yell on the balcony and fights would erupt in the hallway. Once, when Allison trudged down to security in pyjamas to complain, she saw a guard in the lobby riding a hoverboard. “I’m on my break,” he said. A couple of other times, she asked security to call the police, but the noise always returned.

The condo’s outdoor pool was like a scene out of Spring Breakers. Young singles busted out their dental-floss bikinis and blared gangster rap. They smoked in the water and smuggled in alcohol against the rules. One day, an older resident asked a group of 20-somethings to simmer down. He told them the pool was for everyone and that they were being selfish. One of the young guys shot back, calling the man old and fat. This went back and forth for a few minutes until—to Allison’s amazement—the men started punching each other.

“There were like 100 people around the pool. Did any of them do anything? Of course not. They all pretended to look away,” she says.

She ran to the lobby, but the guys at the front desk weren’t much help. Enforcing the principles of the condo declaration—that every resident has a right to a nuisance-free living environment—wasn’t really their deal. Every time Allison pleaded with them to do something, they said they were powerless. “You know how hard it is to evict someone?” the manager asked her rhetorically.

And so that was that, as beats of poolside rap continued to pound into the summer sky. Allison packed it in and started looking for a townhouse. She moved out of the building in August.

Complainants often have to leave their buildings to avoid the consternation of neighbours, the stress of the fight, the drain on their resources. I guess that’s the upside of living in this dense, sprawling condo city. There’s always another building somewhere. We’re always spoiled for choice.

Correction

This article originally misstated Jennifer Bell's profession. She is a mediator, not a lawyer. Also, the name of her company was misspelled: it is called Placet Dispute Resolution, not Placet Dispute Resolutions.