Monster Mash

On Guillermo del Toro’s gruesome horror series The Strain, vampires are the new bioterrorists

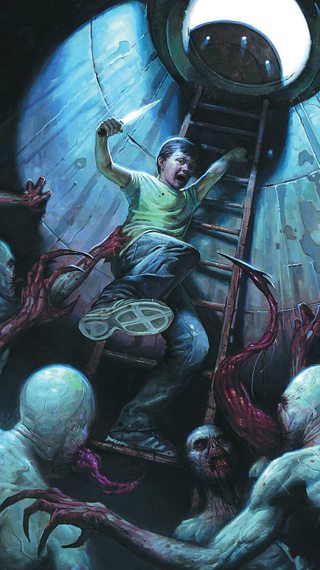

The ghastly creatures—recently seen prowling through Toronto’s downtown core while the show shot its first season here last spring—are the latest in a string of new monsters invading the small screen. Most of these horror series tap into archetypes that have fuelled the genre for eons: the savage cannibal in Hannibal, the Victorian demons in Penny Dreadful, the serial killer in Bates Motel, the asylum patients and witches in American Horror Story.

The Strain does something entirely different: it stokes the fears of our time in a way that makes it feel more urgent than its compatriots. From Dracula in the 19th century through to True Blood and The Vampire Diaries today, we’ve been fed the myth of the ancient seducer. The Strain’s creatures, by contrast, are modern-day terrorists, controlled by an über-vamp whose only goal is to destroy the living. Their weapons are biological and their means fundamentalist.

Instead of an anointed slayer, the vamps battle a troupe of specialists from the Centers for Disease Control. In the first episode, the hazmat-suited scientists are called to JFK to investigate an unresponsive plane on the tarmac, its controls off and doors sealed. Inside the quiet of the plane, they find 200 apparently dead passengers frozen in their seats. Once in the morgue, the corpses suddenly rise from the autopsy tables, shed their human characteristics and begin attacking the people of New York. Soon enough, it’s the good soldiers of the CDC versus the turned.

The show’s most obvious ancestor is F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, a silent film from 1922 about a small town tormented by a vampire overlord—a pointy-headed villain who happens to look a little like the creatures in The Strain. Murnau’s film reflected a pervasive social anxiety: it’s actually about the aftermath of World War I, when epidemics of influenza swept through Europe, destroying entire villages. It was a real menace distilled into a monster. Nearly a century later, in the twilight of globalization, our fears have shifted to invasive species, anthrax attacks, new strains of H1N1. It’s fitting that The Strain’s attacks begin on a plane: we’re terrified of the foreign unknown. And, as our fears metastasize, paranoia becomes the ultimate epidemic.

That paranoia comes from the mind of Guillermo del Toro, the phantasmagoric director who likes his creatures outlandish, his sets moody and his stories biblical. He’s known for warping classic horror motifs to reflect larger social themes: his 2006 breakout film, Pan’s Labyrinth, a bloody feast of art direction, soaked in velvety colours and death imagery, was a parable about Franco-era fascism. In his Hellboy movie franchise, he used a mopey horned monster to explore the alienation of minorities.

The Strain is based on a trilogy of novels co-authored by del Toro and the crime writer Chuck Hogan. Shortly after the first book came out in 2009, former Lost showrunner Carlton Cuse became taken with the idea of developing it into a series. Last fall, the production team took up residency in Toronto, with a prosthetics and special effects crew and a $500,000 budget from FX for creature creation alone. Though he was born in Mexico, del Toro currently lives in Toronto, and he’s shot several films here, including last year’s aliens-versus-robots blockbuster Pacific Rim, the horror movie Mama and the upcoming haunted house movie Crimson Peak.

For the first time, del Toro is extending his brand of allegorical horror to TV, exploiting the medium by cultivating atmosphere, characters and lush aesthetic palettes across a leisurely arc—del Toro and Cuse have planned a five-season run. The writers drop enigmatic clues that will take weeks to piece together. They create characters we’re invested in, like the cocksure epidemiologist Ephraim Goodweather (played with engaging bluster by House of Cards’s Corey Stoll) or the wizened retired vampire hunter Abraham Setrakian (David Bradley, best known as the Red Wedding massacrist Walder Frey on Game of Thrones)—people whose deaths, should they come, will actually matter to viewers. The Strain is such a slow burn that we don’t even fully see the vampires in the pilot. It’s a show that lurks and lingers—letting its horror infect the viewer the way the vampires poison their hapless victims.

TELEVISION

The Strain

FX Canada

Sundays at 10 p.m.

the books are amazing…highly recommend them.