The Captive: John Greyson’s time in Egyptian prison

John Greyson is the quintessential loud-and-proud gay activist—earnest, ardent and perpetually revved up about one cause or another. On a trip to Cairo last year, after being arrested, beaten and thrown into a fetid cell with 37 other men, his subversive background became a serious liability. Fifty days inside Tora Prison

Before he travelled to Egypt last summer, John Greyson had been arrested twice in his life. The first time was in 1983, when he happened to walk perilously close to a bathhouse that was the subject of a police stakeout. The second time was a few years later, at an Eaton Centre “kiss-in” held by the LGBT activist organization Queer Nation. On both occasions, he was held only briefly and was never charged with anything—men making out with men in public, to the chagrin of the cops, was not a criminal offence.

Cairo was frighteningly, confusingly different. Greyson, a filmmaker and professor at York, was on his way to Gaza in the company of his friend Tarek Loubani, a 33-year-old emergency room doctor from London, Ontario. Greyson first met Loubani at the Toronto Palestine Film Festival in 2012. Loubani is of Palestinian descent and had travelled to Gaza before, volunteering at the al-Shifa Hospital. On this trip, he was bringing some routers to help improve the hospital’s Wi-Fi, as well as a pair of small remote control helicopters used to transport blood samples and medical tests through crowded cities. Greyson was interested in Loubani’s work and hoped to get some B-roll footage for Jericho, a film he was working on that was partly set during the Gaza War of 2009. He planned to stay three weeks.

The two men arrived in Cairo the evening of August 15, intending to proceed the next day to the border. After the 2011 revolution that overthrew Hosni Mubarak and led to Muslim Brotherhood member Mohammed Morsi’s election, Loubani had been able to travel easily from Egypt to Gaza. Both he and Greyson obtained the necessary transit visas. What they didn’t realize was that while they were en route, Egyptian security forces, who had overthrown Morsi in a military coup, massacred hundreds of pro-Morsi supporters at sit-ins in Cairo. When they got off the plane, the city was under curfew and their jumpy cab driver, who told them little about what was going on, couldn’t get past a barricade two kilometres from their hotel. They made the rest of the trip on foot, and when they got to the hotel and saw the news, they learned a demonstration had been planned for the next morning at nearby Ramses Square.

Cairo was at a standstill, and Loubani and Greyson were unable to get a car to Gaza. They decided to check out the demonstration. It started peacefully enough, with a crowd gathering just after morning prayers. But soon the army began to fire tear-gas canisters into the crowd, then bullets. After the first wounded body appeared, Loubani, who’d identified himself as a doctor, was directed toward an improvised field hospital in a nearby mosque. While he treated the wounded, his friend Greyson was asked by medical personnel to use his video camera to document the carnage. Greyson believes that artists have a responsibility to bear witness and engage with the world—what he calls a “Hippocratic oath for artists”—and he didn’t hesitate. He trained his camera on each bleeding protestor who arrived at the mosque, tilting in a single shot from their faces, for identification, to their wounds. Greyson and Loubani worked for six hours and watched the carpet of the mosque turn from green to red as it got soaked with blood. “It’s hard for me to remember that lay people do not deal daily with death,” Loubani says, “but John performed admirably in a fucked-up situation.” The field hospital became a makeshift morgue, and Greyson just kept filming. “I was having these Scarlett O’Hara moments,” he says now, recalling the famous shot from Gone With the Wind when Scarlett steps into the field hospital and sees the floor littered with dying soldiers. By the end of the day, he saw 40 people die.

On the way back to their hotel in the sweltering heat, Greyson and Loubani stopped at a convenience store for ice cream. Guards at a checkpoint near their hotel detected Loubani’s Palestinian accent, confiscated their passports and took them to a police station. There, they were searched and interrogated for several hours. Loubani’s nose was bloodied, the cops threatened to burn him alive, and he and Greyson were accused of being international terrorists. It didn’t help that the cops found the memory cards from Greyson’s camera stashed in an ice cream bar wrapper. Six hundred people were rounded up and arrested that night. “They kept saying, ‘You’re Hamas,’ ” Greyson remembers, “and I was tempted to say, ‘Yeah, that’s how desperate Hamas is these days, that they’re recruiting gay Canadian experimental filmmakers.’”

The next morning, still not yet charged with anything, they were loaded with about 40 exhausted, dehydrated protestors into a stifling police van—the temperature that day in Cairo was in the high 30s—and driven to the sprawling Tora Prison, notorious for its grim conditions. (Greyson learned weeks later that police threw a canister of tear gas into another van that held 45 prisoners. They locked its doors, sealing the prisoners inside; 37 suffocated and died.)

They spent three hours in the van, with some men passing out from heat stroke, others soiling themselves. And then it got worse. At Tora, Greyson, Loubani and their fellow prisoners were pushed past a gauntlet of guards who punched and kicked them. They were then thrown into a cafeteria, where they were made to kneel on the cement floor with their hands behind their heads. Greyson could hear the guards systematically beating the other prisoners behind him, slowly making their way toward him and Loubani. He was kicked with such force that he wouldn’t be able to sit up properly for days, and for a week afterward, the imprint of one guard’s boot was still visible on his back. As a final punishment, the guards doused them with buckets of urine.

Thirty-eight men were shoved in a cell that measured three by 10 metres. There were no beds or mattresses, just a concrete floor alive with cockroaches. A single tap provided water, straight from the Nile, for washing and drinking, and a wooden cubicle enclosed a toilet. Their money and credit cards were taken from them, their heads shaved, their shoes and clothes exchanged for white cotton jumpsuits silkscreened with the word “Investigation.” Greyson and Loubani were ordered to sign the same laundry list of charges—everything from trying to blow up a police station to murder—that all were made to sign. (It was not an admission of guilt but an acknowledgement that they were being investigated for these crimes.)

Greyson was certain they wouldn’t be held for long. It had been a savage day and night, but surely this was all a terrible misunderstanding. As he had repeatedly said to his captors, they were Canadians—he a professor, Loubani a doctor. They had no stake in Egyptian politics. “The whole time I was thinking, ‘We’ll be out in 24 hours,’ ” Greyson says. “Oh, were we ever wrong.”

Greyson’s sexual orientation made his predicament especially perilous in a region notorious for its intolerance of homosexuality. On top of that, anyone with an Internet connection could quickly learn that, for much of his life, he’d been involved with various left-leaning, even subversive, political groups. He’s known for his recent work around Palestine solidarity, and in Egypt, anti-Palestinian sentiment—in particular a hatred of Hamas—is deeply ingrained.

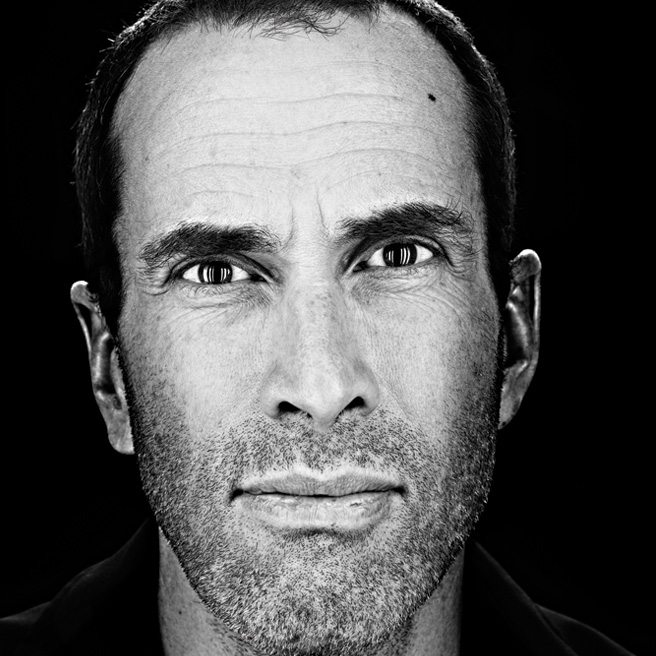

Greyson is 54 years old but looks a decade younger, tall and fit, with short-cropped dark hair and the reflexive smile of a kindergarten teacher. He can be so disarmingly amiable that it’s difficult to imagine him disputing a Scrabble score, let alone Israeli domestic policy. Even his earnestness—and what activist isn’t earnest?—is blunted by an unguarded, boyishly goofy quality. A rebelliousness runs throughout his twin vocations. He’s moved swiftly back and forth from video art to big-budget feature films, episodic TV, YouTube agitprop and documentary opera, a field Greyson pretty much has to himself. The political causes he’s been drawn to have been comparably eclectic, but are all pointedly concerned with ideas of self-determination: the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, South African apartheid, gay rights.

He was raised in London, Ontario, the son of a Western botany professor and a homemaker. It was a large family—Greyson, a middle child, has two brothers and two sisters, and the household was both religious and progressive. His parents, Richard and Dorothy, were liberation theologists avant la lettre, and often participated in social justice causes. “Pete Seeger was constantly on the turntable,” Greyson’s youngest sister, Cecilia, remembers. Dorothy, who had unrealized creative ambitions, taught all the kids to draw, and Greyson was a willing, enthusiastic adept. In high school, a broad-minded art history teacher introduced him to Artforum and the cutting-edge performance and video art of the day. Drawing suddenly seemed old-fashioned. Greyson made his first tape, a surrealistic family portrait, in 1977.

He was sexually precocious, too. He had a nominal girlfriend, but they would often go dancing at HALO (the Homophile Association of London, Ontario), a gay club housed in a former Kellogg’s factory. In After the Bath, a documentary that Greyson made for the CBC about London’s “kiddie porn” scandal of 1993, he talks about being 16 and meeting older men in the basement washroom of the London Public Library. “The sex may have been tacky,” he recounts in a voice-over, “but it was something I’d wanted, something I’d chosen.”

He left high school a credit shy of graduating and immersed himself in Toronto’s avant-garde art scene. He dated A. A. Bronson, a founding member of the conceptual art collective General Idea, and Colin Campbell, the pioneering video artist. And as he continued to make video art, a magpie, mash-up oeuvre took shape: politically engaged, often erotically charged, disdainful of genre and borders, and playfully populated with figures like Rudyard Kipling and Liberace.

Greyson made 14 videos in eight years, and his first feature-length fiction film, Urinal, which “starred” a pantheon of dead gay artists (Sergei Eisenstein, Langston Hughes and Yukio Mishima among them) won a best feature prize at the Berlin film festival. In the early ’90s, he became associated with the so-called New Queer Cinema, an emerging generation of unabashedly sexual writer-directors like Todd Haynes, Tom Kalin and Gregg Araki. Greyson’s film work, however, was more experimental than most, filled with philosophy, farce and talking animals. Zero Patience, his 1993 breakout movie, was a campy meta-musical about AIDS, memory and homophobia. Even his best-known work, Lilies, which won the Genie for best film three years later, is an enigmatic fantasia set in a Quebec prison. If Jean-Luc Godard spent a bit more time with drag queens, he might have made films like these.

One of Greyson’s favourite formal techniques is the split-screen. You can picture, in the story of his life, a perfectly bisected but unified frame: on one side, the art-house filmmaker, and on the other, the political firebrand. He made tapes about the NATO bombing of Serbia and the 2001 Summit of the Americas in Quebec City (the four-minute video, Packin’, consists entirely of shots of cops’ crotches). Though he never finished high school, he started teaching full time at York, where he is currently a tenured professor in the film department.

Since the late ’90s, he has lived with the visual artist Stephen Andrews, and the two have become an influential couple in the Canadian art world (the AGO is planning an Andrews retrospective for 2015). They first met in 1980, and several years later, when Andrews and his then-partner, the writer Alex Wilson, were diagnosed with AIDS, Greyson became part of Wilson’s care team. In 1993, Wilson passed away at the age of 40. Andrews survived, his life saved by new medications he began taking in 1996. He and Greyson became lovers, and a couple of years later bought a Victorian semi in Trinity Bellwoods, where they still live. Almost every inch of the bright, airy house is adorned with their own artwork or that of friends. Andrews paints in a purpose-built glass-walled studio in the backyard.

Greyson’s career has had many controversial moments, but in the last few years, he’s earned new notoriety for his criticism of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. In 2008, he helped form Queers Against Israeli Apartheid, a coalition of pro-Palestinian gays and lesbians opposed to “pinkwashing”—the promotion of Israel as an oasis of gay tolerance in the Middle East to distract from the state’s violation of Palestinian rights. That summer, QuAIA marched in the Pride parade. In subsequent years, the group was denounced by B’nai Brith, the Canadian Jewish Congress and various city councillors, and Pride’s municipal funding was threatened. In 2009, saddened and enraged by the month-long conflict during which both Israel and Hamas fired rockets into civilian areas and more than 1,300 Palestinians were killed, Greyson joined the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. When his documentary opera, Fig Trees, was selected for the Tel Aviv International LGBT Film Festival, he pulled it in protest of the continued Israeli apartheid.

Later that year and closer to home, he withdrew his short film Covered from TIFF because of the festival’s spotlight on Tel Aviv in its City to City program. It was a difficult decision for Greyson—he considered TIFF a kind of informal film school for him, and it had, over the years, shown much of his work—but pulling a film, he told me, “is one of the few things filmmakers can do, in terms of real power. It’s a way to speak out.” Greyson and several other cultural figures, including Naomi Klein, published an open letter, “No Celebration of Occupation,” which was then endorsed by the likes of Alice Walker, David Byrne and Viggo Mortensen. It stated, “We protest that TIFF, whether intentionally or not, has become complicit in the Israeli propaganda machine.”

The letter might have been a rocket itself, and it ignited a firestorm at the festival. A retaliatory letter, signed by David Cronenberg, Jerry Seinfeld and Natalie Portman among others, and published in the Los Angeles Times and the Toronto Star, argued that “blacklisting [Israeli cinema] only stifles the exchange of cultural knowledge that artists should be the first to defend and protect.” TIFF artistic director Cameron Bailey, who had programmed the spotlight and is an old friend of Greyson’s, was hurt and disappointed by the protest. “There was a real misunderstanding about what we were trying to do,” he says now, arguing still that the festival’s programming had never been compromised. “I felt it was a good time to engage, and they felt it was precisely the time to disengage.” Greyson and Bailey didn’t speak again until this past January. “I thought After the Bath would be the hardest thing I’d ever do,” Greyson says, “but going to bat for pedophiles has nothing on going to bat for Palestine.”

In the wake of the protest, Greyson began to routinely receive death threats and hate mail. Producer Robert Lantos published his own outraged op-ed in the Globe and Mail, calling Greyson and Klein “armchair storm troopers” and “Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s local fifth column.” Greyson was undeterred and decided to go even further. Angered by the Israeli raid on the so-called Gaza Freedom Flotilla in 2010, during which nine activists were killed, he joined 1,000 other activists in a second convoy attempting to ferry medical supplies and aid to Gaza. But the Canadian ship, coincidentally named for Cairo’s Tahrir Square, never made it. The Greek coast guard intercepted the Tahrir and forced Greyson and his shipmates to return to port.

In Tora, Greyson’s life was largely reduced to negotiations around the water tap. His fellow inmates were all devout Muslims and, from the outset, they established a routine that allowed them to pray three times a day (rather than the customary five) and wash before each prayer session. Cleaning before and after their two daily meals was also necessary, and the co-ordination of 38 men, one tap and one washrag fashioned from a torn jumpsuit leg demanded extreme logistical rigour. “We were all so bored,” he says. A “food team” was created, which parcelled out the meals served by the guards in large plastic bins—beans, rice, pita, occasional vegetables from the prison garden, all eaten with their hands.

Greyson’s fellow inmates weren’t criminals, but construction workers, blacksmiths, professors and students, all rounded up at the protest and many in jail for the first time. Though some were grandfathers, he was the oldest person in the cell. They were, as Greyson recounts, unfailingly kind. Right after Greyson was beaten and couldn’t sit up, one man, whom he nicknamed Kettle after he somehow manufactured a crude teakettle out of a couple of nails and bottle caps and some wire, cradled Greyson’s head in his lap. Visiting families shared their food. In turn, Greyson taught his fellow inmates English, and Loubani taught them the lyrics to “Que Sera, Sera,” calling it a song of revolutionary struggle. A cell leader was elected, and Greyson loaned him a wristwatch that Andrews had given him. Its glow-in-the-dark dial served as a flashlight for anyone looking for the toilet in the middle of the night.

The only threat of violence came from the guards. For weeks, Greyson trembled uncontrollably every time the guard who’d left his bootprint on Greyson’s back passed by. Occasionally, prisoners in other cells were dragged off to interrogations and returned badly beaten. Others who were caught with drugs or cellphones received similar punishment.

Loubani and Greyson’s detention was arbitrarily, cruelly extended without explanation—24 hours became 48, 48 hours became 10 days. Once a week, the prisoners received boiled chicken. From each of these meals, Greyson tried to save an intact wishbone—gesturing to a collection of wishbones he and Andrews keep at home “for a rainy day”—but each time, the bone would break. “It became a recurring metaphor,” Greyson says. “Another week, another week.” When his customary good cheer failed him, Greyson would lie down on the floor and pretend to sleep, the only way to get any privacy. On one such day, Ray-Ban, an inmate Greyson had nicknamed after his beloved sunglasses, put his arm around Greyson and said, “Oh, John, que sera, sera.”

Loubani’s cellphone was confiscated at the police station when they were arrested, but just before that, he was able to call Justin Podur, a York environmental studies professor. Podur and Loubani have been friends for several years and had formed a mutual insurance plan—if either got into trouble while travelling abroad, the other would be the first person he contacted. Podur alerted the Department of Foreign Affairs immediately, but it took consular staff a few days to find the Canadians (they were registered under their first and middle names rather than their surnames).

Stephen Andrews was sunbathing at Hanlan’s Point when he got the call from Podur. “A day at the beach became a nightmare at the beach,” he says. But he and Podur, along with Cecilia Greyson and Loubani’s brother, Mohammed, swiftly mobilized friends and family. Over the next few weeks, they alerted media and applied pressure in every conceivable way, both in Egypt and in Canada. Mohammed hired an Egyptian lawyer to represent Greyson and Loubani in Cairo, while Andrews was in constant contact with a Foreign Affairs caseworker, sometimes several times a day.

Consular staff and their lawyer were permitted to see them for 10 to 20 minutes a week. The consular staff photographed the bootprint on Greyson’s back and told him to keep quiet about it for the moment—they didn’t want to aggravate the Egyptian authorities, who had searched Greyson and Loubani’s hotel room and found what they called “illegal weapons.” During each weekly visit, they were surreptitiously given pens and paper, which Loubani hid in his underwear; Greyson drew portraits of his fellow prisoners, and both he and Loubani wrote letters that they in turn smuggled to their lawyer. Although the lawyer appealed their detention and submitted complaints to various Egyptian authorities, each visit brought fresh disappointment. Even at a scheduled hearing during which the lawyer planned to present documents showing the two were on a humanitarian mission, the prosecutor handling the case failed to show up. Frustration became fear that they could be jailed for years as the court process dragged on.

The Harper government took the case seriously, but initially dragged its feet, waiting for the Egyptians to lay charges. On the American radio program Democracy Now!, Naomi Klein insisted that Harper pull foreign investment from Egypt and unequivocally demand their release. Her father-in-law, Stephen Lewis, called Egypt’s ambassador to the United Nations.

Andrews, for his part, enlisted well-connected friends like the art collector and philanthropist Salah Bachir to make personal appeals to Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird. Former Ontario premier Bill Davis made his own calls to Baird. The mobilization was impressive, but the men remained in prison. “It felt like being punched in the stomach every morning,” Cecilia says. More than 150,000 people eventually signed a Change.org petition demanding Greyson and Loubani’s release. At TIFF that September, Sarah Polley, Michael Ondaatje and others held a press conference highlighting the detention, and more than 300 celebrities, including Noam Chomsky, Alec Baldwin and Charlize Theron, signed an open letter demanding that the two be freed. Emma Thompson was photographed wearing a #FreeJohnandTarek button. Most improbably, Eve Ensler, the author of The Vagina Monologues, who had met Greyson once, called her friend John Kerry and asked him to raise the issue in a meeting he had with the Egyptian foreign minister.

“A lot of different interest groups focused on these two men,” Andrews says. “The medical community, the art community, the academic community, the activist community. I think both the Egyptian and Canadian governments were like, ‘Who are these guys?’ ”

Greyson told his fellow inmates that he had managed to make four films set in prison before ever setting foot in one. “In Canada,” he said, “we make our movies and then we do our research.” He was careful, however, to omit any mention of the films’ gay content. Outside, the Free-John-and-Tarek team did likewise. Andrews and Greyson are friends with James Loney, the gay Canadian peace activist who was kidnapped in Iraq in 2005, and they saw how the media co-operated in keeping his homosexuality a secret. Andrews coached reporters and supporters not to mention Greyson’s sexuality at all, and he strenuously tried to restrict what people might find in a Google search of Greyson’s name. “We thought, if we could just focus the reporters on Egypt,” Andrews says, “and talk about the professor-filmmaker, we could at least control the first page. Nobody goes to page two in Google.”

On their 30th day in prison, they went on a hunger strike, demanding to be tried or freed. Greyson was terrified of solitary, the usual punishment at Tora for such a protest, so he and Loubani decided to stage a liquids-only strike—physically safer and, in the eyes of prison officials, inauthentic and not necessarily punishable. They described their strike in an 18-page letter that also detailed, for the first time, the abuse they’d suffered and gave it to their lawyer to circulate publicly.

The strike and the letter had the desired effect. The Egyptian media reported on the abuse and, at 1:30 a.m., prison officials appeared at their cell to investigate their claims. Just as time had slowed so painfully, all at once it seemed to speed up. The PMO issued a statement demanding their immediate release.

Then, most significantly, Loubani’s father, Mahmoud, who lives in New Brunswick, travelled to Cairo to visit the prison and lobby the minister of the interior for his son’s release. The sympathetic politician let Mahmoud into his office and allowed him to address the entire Egyptian cabinet via speakerphone. Egypt’s army chief, General Abdul-Fatah Al-Sisi, who was on the line, said Mahmoud would not leave the country without his son.

He wasn’t lying. Within a week, 50 days after their arrest, the men were released without explanation or apology. By that point, they had been transferred to a smaller cell with only six other prisoners, and, at first, Greyson thought they were just being moved again. When he realized it was not a trick, he was overcome with emotion. There was relief, of course, that the ordeal seemed to be over, but also the realization that the men he was leaving behind were still trapped in the same excruciating limbo. The consulate hustled them, and Loubani’s father, to a hotel near the airport. There, because of legal technicalities, they endured four more days of waiting before finally flying out of Cairo. In a short video that Greyson made just weeks afterward, Prison Arabic in 50 Days, he shows a series of flashcards he made, with drawings of various objects and people from Tora. One depicts his glow-in-the-dark wristwatch, accompanied by the word, in Arabic and English, “Enough.”

Greyson and Loubani were met by dozens of reporters when they arrived at Pearson. They gave a press conference, thanking the thousands of people who helped secure their release, explaining what they had gone through and what their fellow prisoners continued to go through. Exhausted and much thinner than he had been when he flew to Egypt in August, Greyson took the opportunity to press a point about activism’s power: “We learned that pressure from concerned citizens does work,” he said, “that petitions make a difference, that grassroots and mainstream strategies…can work together to bring about this very happy day.” After the press conference, they headed to Podur’s house, where Andrews and Cecilia Greyson were waiting with pizza and chicken wings. At the Gladstone a few weeks later, the documentary filmmaker Avi Lewis hosted Tarek and John’s Jail Break Cabaret, a party celebrating their return.

Not everyone was so pleased. The Globe and Mail columnist Margaret Wente and Sun News’s Ezra Levant questioned Greyson’s heroism and criticized what they, like the Egyptian police, believed was his support of Hamas. Wente also aired her feelings about government support for the arts and Greyson’s box office returns: “His gay-themed films, financed with government handouts, have been commercial flops,” she wrote.

Andrews was worried that Greyson might have post-traumatic stress disorder when he returned, but no symptoms ever materialized. He hasn’t been in therapy in years, but when he returned from Egypt, his former therapist called to check in. “I’ve been binge-watching Glee,” Greyson told her. “Does that count as PTSD?”

Imprisonment has, it seems, only hardened his revolutionary resolve. Just three weeks after being released, feeling new kinship with those in jail, he spoke at a press conference with Loubani about the indefinite detention of immigration detainees in Canada, and at Western this past January, he was a special guest of the Prisoners’ Justice Film Festival. He’s campaigned to free Mohammed Fahmy, a Canadian Al Jazeera producer imprisoned without charges in Egypt last December. “He knows that people are still in prison,” Cecilia Greyson says, “and that’s a burden now. He’s always been a person who’s carried a lot, and now there’s an additional weight to carry.” He’s already planning the QuAIA float for this year’s Pride parade—it’ll likely feature a drag queen playing Scarlett Johansson, the spokesperson for SodaStream, the Israeli carbonated water product that some people have boycotted. He’s at York at least three days a week, scrambling to catch up on his teaching duties.

In Gaza, meanwhile, activists are currently retrofitting a fishing boat that will be used to try to break the blockade. No one has asked Greyson to join them, and in any case, he says, he won’t be heading back soon. “I can’t do that to my family and to Stephen again,” he says. “I have to focus on making films right now.” Every Monday, at an iMac in his book-lined attic office, he pokes away at Jericho. The essay-film is about several things at once: the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, gay marriage, Arnold Schoenberg’s Moses und Aaron (Greyson’s desert-island album is the Stuttgart Opera’s recording) and John Cage. And after he finishes Jericho, he’ll immediately start work on another opera film, Baghdad, which uses footage Greyson shot while teaching a workshop at the Iraq Film Institute a few months before he left for Cairo.

He’s also started making what he calls “running portraits” of the men he left behind at Tora. Using a GPS running watch, he maps routes around Toronto whose points describe the contours of the prisoners’ faces; the somewhat crude portraits are then printed out. The longer he runs, the more points on the route and the more accurate the portrait. As of this writing, he’s made about a half-dozen.

The idiosyncratic technique has great metaphoric potency. It signals that Greyson is free now, and free to make art any way he wants—even using his own body as a kind of pencil. It is at once a gesture of celebration and anger, endurance and remembrance. It is also a way to acknowledge what had been taken from these men, and what he was so lucky, finally, to have back.